The average life expectancy in the mid-1800s, in North Yorkshire, was about 25.6 years. By the time the novel opens, sure enough, most of the characters have gone to their graves, and only the dark, brooding, heathen-ish Heathcliff remains. He’s been made much of (as a hero) over the centuries since Wuthering Heights was first published, but really, he’s not a man you want around. Anytime.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë had been published earlier in 1847, and the British edition of Wuthering Heights came out in December, 1847. This, American edition of Wuthering Heights, published in April, 1848, mistakenly attributed the novel to Charlotte. Both the British and American publishers thought that the three Brontë sisters, writing under the pseudonyms of Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily) and Acton (Anne) Bell were the same person.

The only way to prove that they weren’t one person, was to have two of them, Charlotte and Anne, travel to London and arrive unannounced at the British publishing house, with a ‘here we are, two of three, and not only one at all.’

Wuthering Heights is still breathtakingly beautiful. It’s Emily Brontë’s only novel, and her first book, and much like the novel’s characters, she died young also.

There is a mere clutchful of characters in Wuthering Heights, all alternatively named either Earnshaw, Linton, or Heathcliff, which can be, and is, confusing. It’s a tightly woven world, mostly set in the eponymous Heights, or at Thrushcross Grange, four miles from the Heights.

At its core, the novel is the story of the love between Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw, or rather, as you will come to realize, the introduction of Heathcliff into the narrative, sets the plot into progress.

Emily Brontë was a teacher at Law Hill school in Halifax, for six miserable months, before she returned home. It was here she most probably heard the story of a local man, Jack Sharp, and his quarrels with his neighbors, which formed the plot for the novel. And close by, was High Sunderland Hall, which became, so it is said, Wuthering Heights in the novel—although the Heights is set nearer home in the book, in the Haworth countryside where Emily lived. Source.

It comes on slowly, this main plot. First, we’re introduced to a wealthy young man, Lockwood, who has rented Thrushcross Grange in the wild Yorkshire moors in search of solitude and to recover from a hectic life. The seclusion palls soon enough, and he goes seeking his landlord at Wuthering Heights. Heathcliff is a surly host, flanked by two equally churlish youngsters—a teenage girl and boy. The girl, Cathy Heathcliff, is the daughter-in-law, the boy, Hareton Earnshaw is a brute, and treated as neither guest nor servant, and yet, his name, ‘Earnshaw,’ adorns the lintel over the front door. Lockwood persists in visiting, once during a snowstorm, when he’s forced to shelter there overnight. He has a nightmare in his room, a bough knocks against the window, and when he opens it, a child’s cold hand clutches his, all the while pleading to be let in. Lockwood is petrified. Stranger than that is Heathcliff’s reaction—he rushes to the window and begs for ‘Catherine,’ to come back, to come in.

Lockwood returns home to Thrushcross Grange, sick, tired, appalled, and corrals the housekeeper, Nelly Dean, into telling him the story of those bizarre inhabitants at the Heights.

Earnshaw père, father of Catherine and Hindley, lived at Wuthering Heights, and one day, the father Earnshaw brings home a foundling, a rough, wild boy. This boy they name Heathcliff, and he grows up with the two other children. Hindley hates this usurper of family affections; Catherine, makes him her companion and very soon, begins to roam the moors with him, as untamed and uncouth as Heathcliff.

High Sunderland Hall on the outskirts of Halifax in Yorkshire, said to be the inspiration for the Wuthering Heights house. The photograph dates to 1913—by the mid-1950s the building was torn down. Source.

When the father Earnshaw dies, Hindley becomes master at the Heights. He’s married by now, and proceeds to make Heathcliff’s life miserable. When Catherine is injured during one of these moor jaunts, the Lintons at Thrushcross Grange carry her into their home and dismiss Heathcliff.

The Lintons have two children—Edgar and Isabella, pink and white proper offspring, clad in fine clothing, stately mannered, everything Heathcliff is not. Catherine stays with them while she recuperates—Hindley encourages this—and returns home a superior young woman. Even as Edgar and Isabella gain an influence over her, Heathcliff’s seems to lessen and he’s banished to the kitchen and the scullery.

As they grow up, Edgar falls in love with Catherine almost inevitably, and proposes to her. Catherine is, in her own, way a special kind of unruly child; selfish, arrogant, pampered, expecting privileges, inconsiderate of others. She tells Nelly Dean that she accepted Edgar because he will make her mistress of Thrushcross Grange, and it’s a life of wealth—something Heathcliff could never give her. Heathclifff overhears this conversation, and rushes out of the house besieged by a madness and doesn’t return.

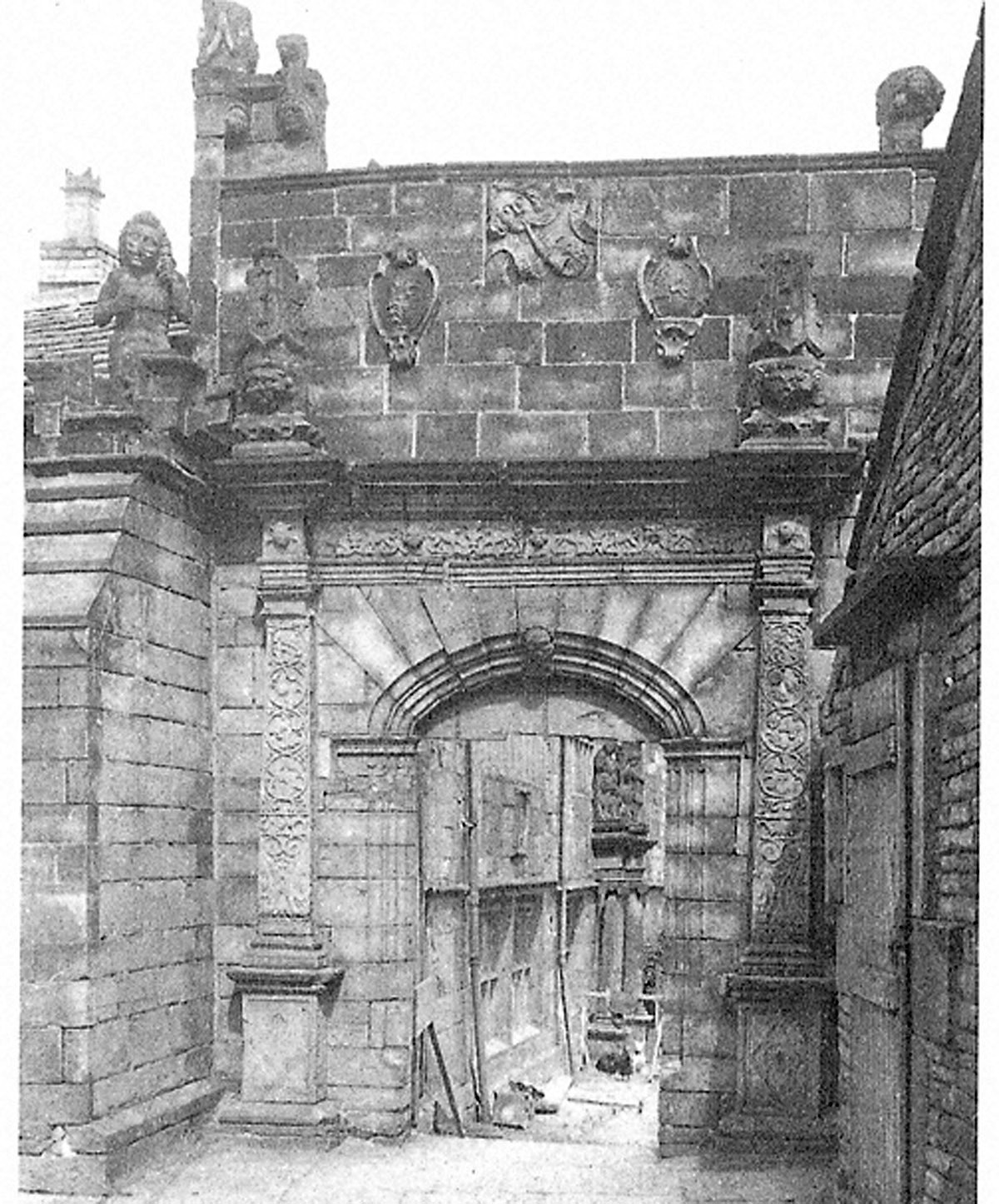

The front gateway of High Sunderland Hall (said to be the model for Wuthering Heights). Here’s Lockwood describing his first impression of the Heights in the novel: ‘Before passing the threshold, I paused to admire a quantity of grotesque carving lavished about the front, and especially about the principal door…’ Source.

Three years pass. Hindley Earnshaw and his wife have a child—that Hareton Earnshaw whom Lockwood meets at the Heights. The wife dies, and Hindley dissolves into a gambling drunk, neglecting Hareton, and leaving his upbringing to Nelly. Catherine then marries Edgar Linton and persuades Nelly to come with her to Thrushcross. There, Catherine is petted, and with a doting husband and sister-in-law, life is evenly happy.

The demons don’t rise.

Until…Heathcliff returns, now mysteriously a wealthy man, his hair cut, his clothes fitted and gentlemanly, his speech refined. He begins to visit Thrushcross and Edgar grudgingly allows this ‘friendship’ of a man he detested (because he suspected that strong bond between his wife and this man). All this fraternizing with Heathcliff leads Isabella Linton to fall in love with him, despite warnings of his true nature from both Nelly Dean and Catherine. She persists, and Heathcliff, awakened to the possibility of getting more under Edgar’s skin if he marries his sister, encourages her interest.

…and, the same gateway to High Sunderland Hall from the inside. Source.

Matters soon come to a head in that uneasy triangle of lovers—Catherine, Heathcliff and Edgar, and Heathcliff is kicked out of Thrushcross. Catherine flings herself into a tantrum and makes herself ill. On that very night, not knowing this, Heathcliff elopes with Isabella and on the way out, hangs her dog from a hook on the wall in front of her. Later, he will say that he does this so she knows his true character before she marries him.

When they return from this ‘wedding trip,’ two months later, Catherine is just beginning to recover, and Isabella is no longer under any illusions about her brutish husband, including the fact that he’s really in love with Catherine. Heathcliff haunts Thrushcross until Nelly lets him in to see Catherine and she’s witness now, and finally, to the intensity of their love. They’ve put aside the conventions that they’re each married to someone else, and clasp arms around each other passionately. “Go,” Nelly says, frightened, before anyone comes back home. Heathcliff finally leaves, and Catherine gives birth to a baby girl that night…before dying.

Her death is something awful for everyone. Edgar is heartbroken, for he truly loved her. Heathcliff turns more into a maniac, a savage who haunts her grave in the churchyard, and Isabella leaves her husband and escapes to London, where she gives birth to a baby boy, whom she names Linton Heathcliff, marrying those two names together. A few years later, she also dies.

Edgar Linton brings his nephew home for the short space of a day and a night, before Heathcliff comes knocking on the door to claim his son. Hindley, Catherine’s brother, is dead now also, leaving his son Hareton in Heathcliff’s care, and leaving Wuthering Heights to the man, because Hindley gambled away his property, and mortgaged it to Heathcliff.

As Linton Heathcliff grows up in Wuthering Heights—a sickly, effeminate child, much to Heathcliff’s disgust, and Cathy Linton grows up in Thrushcross—much in the mold of her flighty mother Catherine, but still very much loved by her father, a predictable interest springs up between these two cousins.

The main door into the house at High Sunderland Hall. Source.

Relationships are muddled and messy in this novel, since they all fall in love and marry within a tight circle. But, Linton and Cathy are cousins because the former’s mother, Isabella, and the latter’s father, Edgar, are brother and sister. And, Cathy is also first cousin to Hareton, because her mother Catherine was Hareton’s father, Hindley’s sister.

Hareton, though, is another vulgar youth, unlettered and illiterate, first neglected by his drunken father, Hindley, and then treated with contempt by the man who owns his property, Heathcliff.

Cathy and Linton write secret, loving letters to each other—they’re forbidden to meet, naturally, since Edgar and Heathcliff detest each other. Heathcliff encourages this strange ‘love;’ he wants them to marry so he can now get his hands on Thrushcross Grange also. It is a strange love, perhaps the weakest part of the novel to me. Cathy is too much like her mother, bold, irreverent, caring for nothing and nobody. And Linton is this washed out, whining, complaining, sofa-hugging fool. The ‘love’ is explained as pity…but it doesn’t seem enough.

Emily Brontë from a family portrait by their brother, Branwell. It’s about the only established likeness of Emily, and her sisters. Hopefully, Branwell was a skilled artist. Source.

Edgar Linton is now dying, slowly, and Heathcliff, in a rush to get the two married, essentially kidnaps Cathy and Nelly Dean when they’re out in the moors and keeps them captive until a forced wedding ceremony is performed and Cathy becomes Linton’s wife. She, now is the Cathy Heathcliff, the daughter-in-law, whom Lockwood meets at the Heights at the beginning of the novel. Linton, of course, dies well before Lockwood comes to this part of the world.

Here, Nelly Dean’s story ends. Lockwood then returns back to his home in London, and comes back to the moors some eight months later to find many changes. Heathcliff is dead, mourning for Catherine, called to his grave by her, so says Nelly Dean. Cathy and Hareton have struck up a friendship—where she once despised and mocked him for his lack of learning, she begins by offering to teach him his letters. He’s a fast learner, and as he studies, his coarseness falls away and his innate and birth-given refinement nudges in. Lockwood does not meet anyone other than Nelly Dean on this trip, but he does see Cathy and Hareton walking out, hand in hand. That, is the happy ending.

The painting Branwell made of himself and his sisters—Anne, Emily and Charlotte, left to right. He later painted himself out, quite obviously, as you see. Source.

Wuthering Heights is a blisteringly raw book. The Victorian world gasped in horror when it was first published, but they read it—they all read it, and speculated about this man ‘Ellis Bell,’ who wrote it. Emily Brontë, and her sisters, all published their novels under male pseudonyms.

It’s a novel that is laid exposed, stripped of any pretense at civility or civilization, primal in its emotions. Heathcliff and Catherine’s love is a throbbing, awesome thing, rooted deep within themselves, something that can neither be denied nor neglected. They’re both, however, extremely disagreeable characters, offensive and inconsiderate, which has nothing to do with learning manners or sophistication—it’s just who they are. Brontë then tells us that their love is their redemption, however boorish they may be. And, she is such a fine writer that, yes, you will believe it. But once Catherine dies, Heathcliff doesn’t even have that excuse anymore—the hanging of the puppy on the hook before he marries Isabella is just one of his repulsive acts.

He descends into the loathsome for the rest of the book. Which is perhaps why a few movie renderings of Wuthering Heights end their story when Catherine dies, and don’t deal at all with the stories of the next generation. But Brontë takes us there, beyond, and strips Heathcliff bare, shows us the man beyond the lover…and he’s disgusting.

Haworth Parsonage, where Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë lived and where they wrote their novels. We visited the parsonage and then went down to the village for a cup of coffee. On our way back to the parsonage and the car park, we passed the church where their father, Patrick Brontë conducted services. I dawdled, my mother went on ahead. When I turned, I saw her perfectly framed in that warm sunshine, the parsonage ahead, and took a photo. And, converted it into a painting for this blog post.

The novel gallops at an unrelenting pace—this is why the Victorians, aghast as they were, could not put it down—and when Nelly Dean finishes her story and Lockwood leaves the moors for London, that is when your heart begins to beat more evenly, perhaps is even joyful by the end.

I realize that this is not a ‘book review,’ more a sort of Cliff notes on the novel, but it was difficult to figure out how to explain that intense madness within the pages without telling the story, and still encourage you to read it. It is undoubtedly worthwhile.

The original photo I took of Haworth Parsonage.

Wuthering Heights is powerful storytelling. Consider that the three Brontë sisters, who wrote such vehement, passionate novels, were all spinsters (Charlotte married a year or so before she died), living quiet, unoffending lives in a parsonage at the edge of the wild and stormy moors. And even so, the reserved, dreamy Emily Brontë, wrote this dynamo of a novel.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—the king who didn’t exist—who built the cathedral that does—Now I lay me down to sleep—Jane Austen and Winchester Cathedral—Part 1

It’s unbelievable that a foreign speaker writes a review of such quality,hats off Indu.

Thank you!

Such a beautiful write-up, Indu! You have captured the significant events in this novel so well! And I love the picture and painting of Amma!

Thank you, sis!