At the end of September, 1066 CE, William, Duke of Normandy, took a boat across the English Channel to land on the coast of Sussex. A little more than a fortnight later, he had defeated the English king, and established himself sovereign in a Norman Conquest.

So complete was William’s victory that the very character of English society altered beyond recognition. Language, law and politics knelt to Norman rule. The English nobility fled the country in large numbers, or died during the invasion, and their daughters, sisters, and wives who inherited their estates, married William’s French nobility. Most of the high offices in the land—both the laity and the clergy, including the Archbishop of Canterbury—went to the French.

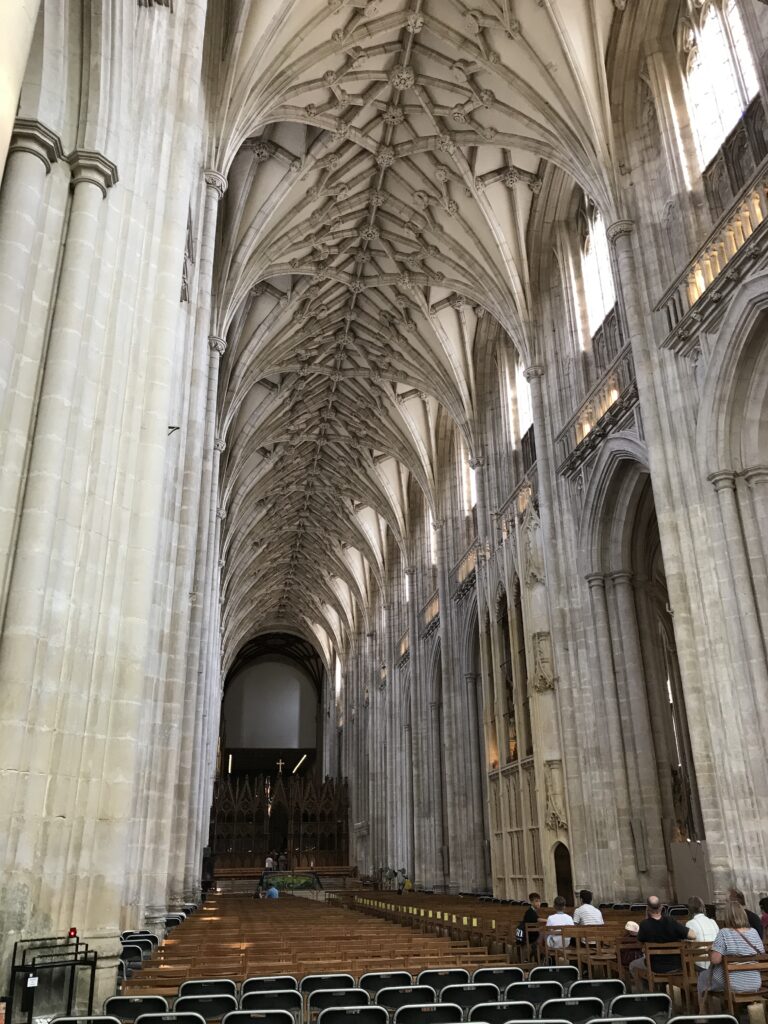

Even in the architecture of England—such as can be seen today—so very little remains of that before the Normans Conquest. On my blog, Bath Abbey, Winchester Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, and even the little Church of St. Nicholas at Steventon where Jane Austen worshipped, all date to Norman rule in England.

The magnificent nave in Winchester Cathedral. I wrote a blog post about the cathedral in following Jane Austen to her resting place, but several Normans are also buried here, and it will crop up several times in this blog post on the Bayeux Tapestry.

A few years after William’s Norman Conquest, someone. . .(we’ll investigate the origins) put together a splendid piece of embroidery on linen, recounting the story of the duke’s annexation of England.

It’s called the Bayeux Tapestry, and is still housed in the town of Bayeux in Normandy in France.

In 1077 CE, William went back to Normandy (for the first time after the Norman Conquest) to attend the consecration of the Bayeux Cathedral (on a future blog post). The tapestry was made for this event, and then, and for maybe centuries after, hung in the cathedral nave.

Let’s step back a little. . .for an (extremely) concise history of England until William came:

The Romans ruled over Britain for four centuries, until about 410 CE—and then, just as the British departed from India after independence in 1947, en masse, literally—the Romans also left that northern island they had conquered and lived in for four hundred years.

(Six centuries later, the Norman Conquest may have changed the English landscape, but the Romans did leave something of themselves—see my blog posts on the Roman Baths at Bath).

In that vacuum, hordes of settlers and invaders came from northern Europe into England. One particular Germanic tribe, the Angles, spoke a form of Old English and lent their name to the very name of the English.

These several incursions into England, after Rome, became the Anglo-Saxons. Initially, they were split into several kingdoms, with much infighting, until England (more or less) became one country. That survived until the Norman Conquest.

(You see me putting Norman Conquest in capitals? It’s fairly normal, because it was such a stunning event for England. The Norman Conquest.)

An even shorter history of Norman France until William:

Because there’s really not much to tell of Normandy until the 10th Century. It was anciently part of old Gaul, until the ‘Northmen,’ also Germanic (Norse Viking mostly) came to settle in northwestern France and mix with the locals. Their name, the Normans, Normandy, the Duchy of Normandy, all came from ‘Northmen.’

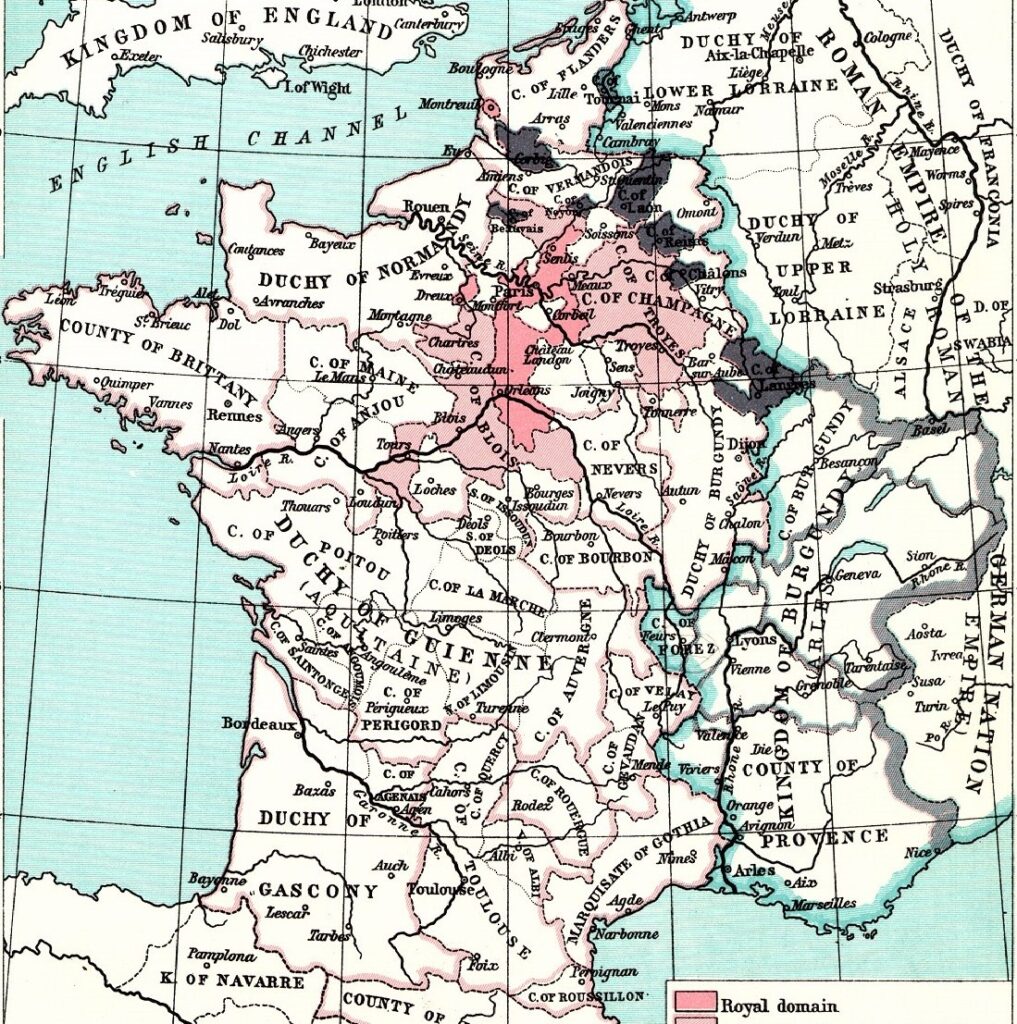

A map of France around 1035 CE. You’ll see how little the ‘King of France’ owned of the land, just that darkened pink around Paris. The rest were independent kingdoms or duchies, each with differing levels of non-alignment with the ruler of France. Image Source: William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, 1926.

12th Century France itself was a collection of kingdoms—the king of France had very little real estate, and little power. He was surrounded by the duchies of Normandy (of course), and Brittany, Aquitane, Gascogne etc., all independent kingdoms, who vacillated in their alliances with the King of France.

In fact, at an earlier period of his rule over Normandy, William had a fairly amiable association with the ruler of France, but it deteriorated greatly before he conquered England. And William carried that enmity over the English Channel into his new kingdom—to such an extent, that it gave birth to the historically frigid relationship between England and France in the ensuing centuries.

So, if we are not to consider William an Englishman (which he most certainly wasn’t), then a Frenchman (who ruled over England) created the rift between England and France!

Interesting theory, that.

I see a fair maiden yonder across the waters:

We’re now at a point where the kingdoms of England have coalesced into a whole country, and the Duchy of Normandy has established its own sovereignty.

And here, a marriage was arranged between England and Normandy, which became the launching pad for William to make that Norman Conquest of England.

ᴁthelred, bestowed with the unfortunate sobriquet of ‘The Unready,’ which defined his entire rule, was the king of England. In the 980s, he was plagued by several invasions by the Danes, his head swiveling from one assault toward the other.

ᴁthelred, frozen on a 11th Century coin. He looks rather sharp here, but his epithet was ‘the Unready,’ as in ᴁthelred the Unready! The ‘unready’ part seems to have been a posthumous designation, a riff on his name, because of the way his life eventually panned out. Image Source.

Duke Richard The Fearless (Richard I) was ruler of Normandy, and ᴁthelred picked a quarrel with him. Something about the Danes selling their English plunder on Norman shores, something about ᴁthelred sending a fleet to land on the coast, and being beaten back, or ᴁthelred having captured Richard the Fearless and bringing him back to England trussed up like a turkey to the pot. The Pope intervened to settle their differences, but the animosities continued to simmer.

When Richard the Fearless died, his son, Richard the Good (Richard II) became the Duke of Normandy.

With the new rule came some wiser decisions. Richard the Good either offered up his sister, Emma, to ᴁthelred, or the latter made the proposal.

Either way, in 1002 CE, ᴁthelred married Emma and brought her back to England. He would have been about thirty-five or thirty-six. She was about eighteen.

Richard the Good was William’s grandfather, and so, Emma was his grandaunt—that is the relationship that gave William the Conqueror his first step into England, a way to establish legitimacy to his claim to this foreign throne. It actually mattered a fair deal to William that he had an excuse, and how do I know this?

We’ll figure it out when we come to the actual story told in the Bayeux Tapestry—because, frankly, more than half the story in the tapestry is the justification for the Norman Conquest!

Emma, Queen of England, wife of two English kings, and mother of two English kings:

That, in the subtitle above, was to be Emma’s fate, a splendid one, you might say.

Let’s examine her name first. Emma. A fairly common English name, you’d think?

Not so. When Emma first married ᴁthelred and came to England, they didn’t like her name one bit. Too foreign, they thought. It was bad enough to have an alien queen. . .well, they didn’t call female consorts queens then, but ‘Lady of the English.’

Let’s change her name then, into something that sounds more English. So, they rechristened poor Emma as the very English (at least it was Anglo-Saxon then) ᴁlfgifu!

(Can we all agree that Jane Austen’s novels are about as English as the English can be? Then, both she and her Emma Woodhouse must be turning over in their graves—who would have thunk that Emma was originally a Norman French name?)

ᴁthelred gave his new bride several towns and villages as her own, including the city of Exeter and she brought her Norman nobles to England as governors and mayors (the Anglo-Saxon word for these administrative officials was ‘reeve.’)

Little did the English know then, but the Norman Conquest of England had already begun.

Alas, this English queenship does not last:

Remember that I’d said the Danes were the premier enemies of the Anglo-Saxons in England? Well, some ten years later, in 1013 CE, a Danish king, Swen, came over to conquer all England and ᴁthelred had to flee the country with his wife and children. Where did they go? Why, to Normandy, of course. His wife’s home.

So now, we’re at a point where the king of England is languishing in exile in Normandy, with his own kingdom in the hands of the Danes.

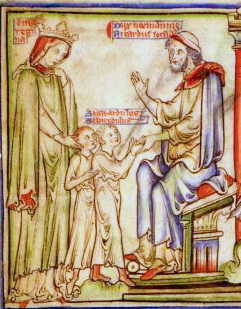

Here’s a very maternal Emma (you’ll see as you read on why I emphasize on that maternity) presenting her two sons, Alfred and Edward (the Confessor) to her brother, Duke Richard II of Normandy, when ᴁthelred and she had to find refuge in France after the Danish conquest. Image Source.

But, another English queenship beckons?

A year later, in 1014 CE, Swen, the Danish conqueror of England died, and was succeeded by his second son, Canute.

Succession to the throne was decided by a council of Wise Men called The Witan. They were comprised of the leading earls, bishops, and thanes (we’ll meet someone with this title later on in this narrative) in Anglo-Saxon England. The Witan’s influence was nominal, their function more ceremonial than actual. In other words, they had little power and did what they were told.

But the Witan’s authority, now, was fortified by prevailing English sentiment among the yeomanry and the gentry, that was very much against these invading Danes.

Canute, who ought to have been king of England by all rights, was kicked out, and our ᴁthelred, aging and infirm, was invited by the Wise Men to don the crown. He did, but some way into his second rule, his oldest son, Edmund Ironside, who was born from ᴁthelred’s first marriage (Emma of Normandy was ᴁthelred’s second wife) rebelled against his father and set himself up as king of northern England.

(Another Jane Austen aside about the English name, Edmund, since I’m a bit of an Austen fan. Edmund Bertram is the main male protagonist of Mansfield Park, a very wishy-washy kind of hero, but in that analysis, I could easily fill another blog post. Maybe, I will, in the future).

Back to old England now. . .

In 1016 CE, two years into ᴁthelred’s second reign, Canute the Dane came back to England and conquered several places. Edmund Ironside joined forces with his father, but just about now, ᴁthelred died, leaving Canute in possession of a large part of England.

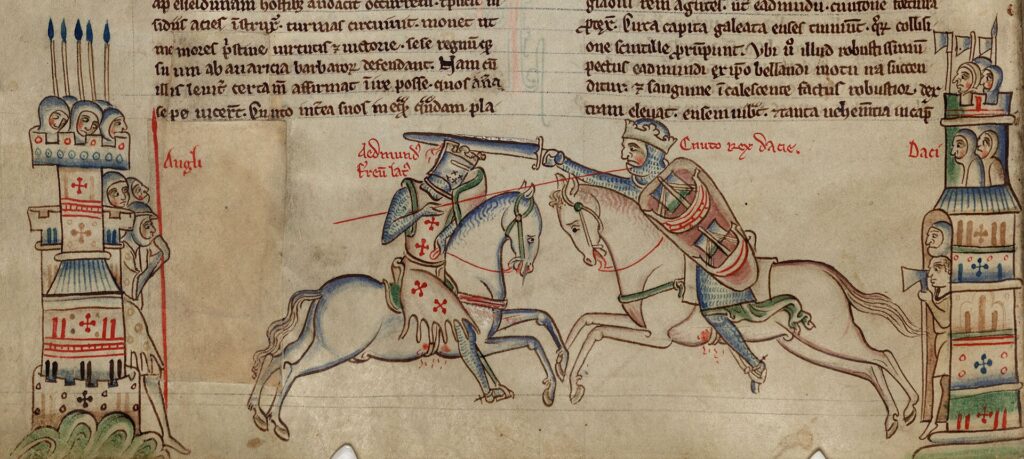

Then, Edmund Ironside died, possibly under dubious circumstances, and Canute was elected ruler of all England now.

Edmund Ironside and Canute in battle—from a medieval manuscript, possibly well after both their reigns? Because Edmund’s demise doesn’t seem to be this clear cut. There was some suspicion that Canute ‘brought about his [Edmund’s] death.’ Image Source.

One the first things Canute did upon assuming his all-pervading kingship was to send for Emma, very recently ᴁthelred’s widow. He wanted to marry her.

An alien queen of England for the second time:

Emma and her first husband, ᴁthelred, had three children, but it doesn’t seem like she cared for them. When Canute’s call came, she abandoned them. Her two sons and a daughter were left in the care of her brother, Duke Richard the Good of Normandy.

As a consequence of not being able to go to England—even though they were an English king’s children—they grew up more Norman and French than English. In a way, their mother’s desertion probably helped to save their lives, because Canute initially set out to exterminate as many of ᴁthelred’s kinsfolk as he could find. Once his bloodthirst had been satisfied, he settled down to becoming a good king of England. He eventually inherited Denmark (from his older brother) and conquered Norway.

Here’s our Emma from an illustration in a 13th Century miniature (well after she died), in a charming representation of true motherhood with her two ‘ᴁthelings,’ her sons with ᴁthelred. One boy is Edward the Confessor (as king of England) and the other is Prince Alfred. This was when she fled England with ᴁthelred, and sought shelter with her brother, the Duke of Normandy. Image Source.

Emma now fulfilled one part of her destiny—she became the wife of a second king. With Canute, Emma became Lady of the English all over again, and they had two children.

Meanwhile in France. . .

Even as Canute ruled, in France, Richard the Good (Emma’s brother, Richard II) died and was succeeded (eventually) by his second son, Robert. Poor ᴁthelred was one of few kings possessed of an ungainly epithet, in being called ‘the Unready.’ Robert, the new Duke of Normandy was ‘the Magnificent.’

Why is Robert important?

Because he’s a direct link to William the Conqueror; Robert was William’s father.

There are some murky accusations against Robert in this gaining of the Normandy crown, as in he deprived his elder brother, who was Duke of Normandy (as Richard III), of his life in doing so—and I’ve a theory that William sets it all right with his own marriage. When we get to William marrying his Mathilda, we’ll look into it, in Part 2.

What claim did Robert and William the Conqueror have upon England?

Robert succeeded to his Norman throne while Canute was still king of England. The Normans thought of Canute (and his Danish father who had first conquered England) as usurpers to the English throne.

Emma’s sons (and the dispossessed English king ᴁthelred’s sons) Alfred and Edward, were living in Normandy—the new Norman duke Robert was their first cousin. It was Robert who had the army—and the might—to pick a fight with Canute.

And, before Canute died, Robert began agitating against him, ostensibly on behalf of his first cousins—Alfred and Edward had a right to the English throne, Canute must be thrown from the land. Or something like that. Most likely, Robert wanted England in a Norman Conquest for himself, and this was one way of pretending that he had a right to fight for it.

Still in quest of an English king for England?

Robert, Duke of Normandy, did not succeed in his quest for England, but it was this motive that gave William the idea of conquering England.

Robert died, and Canute, in England died. They were each succeeded by their sons. Robert’s son, of course, was William, who had a very shaky claim to even the Norman throne, let alone the English one. William was illegitimate. And, William was only seven years old when his father died. Could he hold onto Normandy with this double-disadvantage? We’ll see as we go on.

Canute’s son was the one he had by Emma. And here, with this son of Canute’s, Emma fulfilled the first part of the ‘mother of’ prophecy. She’s still to become mother of yet another—a second—English king.

King Harthacanute—Emma’s and Canute’s son. The first of her sons to become an English king, Harthacanute succeeded his father to the throne. Image Source.

Then, Harthacanute, this Canute-Emma son died in 1042 CE.

At this point, the nobles in England were (again) frustrated with being ruled by ‘foreign’ kings, and The Witan began casting around for an actual English king.

They found one in another of Emma’s sons, Edward, first cousin to Robert, Duke of Normandy (who is dead now). Edward was Emma’s son with the once-king of England (or should I say twice, since he ruled two times) ᴁthelred.

Edward the Confessor is English, is he?

The irony is that Edward was about as French as the French can be. He had been born to ᴁthelred, an English king, for sure; he had even been born in England. But he had grown up in Normandy, steeped in French culture, language and society. Because, when his mother married Canute, she had left him and his siblings in Normandy, without a backward glance, or worry about her children.

With Edward on the throne now, Emma became the mother of the second king of England. And Edward was uncle to the now-Duke of Normandy, William. Our Conqueror. That Norman foot-in-the-door with Emma’s marriage to ᴁthelred, had just wedged the door open a little more.

And then, Emma, supposedly, falls into a bit of trouble.

Having been the wife of two kings of England, and now the mother of a second king of England, Emma had great power at court, which incensed the Bishop of Winchester. He accused her of ‘unchastity.’ To prove her innocence, she had to walk over red-hot ploughshares laid on the paving stones of the nave of the cathedral—and, she came through unscathed. Image Source.

I’m going to get sidetracked a bit here. This reminds me of another woman being tested thus for the same accusation—of being unchaste. In the great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, Rama’s wife, Sita, is kidnapped by the demon king, Ravana. Rama raises an army and goes to rescue his wife. When they meet after the war, he’s hesitant to accept her; has she not lived all these days with another man?

So, a fire is lit on the battlefield and Sita is forced to walk through it to prove her innocence. (Image below). Sita not only survives this Agni Pariksha—trial by fire—but the Lord of the Fire, Agni, himself comes to deliver her from his wrathful flames. Agni’s standing behind her.

Sita’s reprieve was but temporary, eventually, the accusation surfaces again, and Rama sends her into exile, despite her triumph at the trial by fire. Many years later, he wants her back, but, she refuses—nope, not coming back to you; you oughta have believed me the first time. Something like that. Image Source.

Coming back to our Emma of Normandy now, after her own trial by fire, without singeing her feet on the heated ploughshares, she went back to court, and presumably, to power.

She had the last laugh though on that Bishop of Winchester. I’m not sure where he’s buried, but her bones, and those of her second husband, Canute, are said to be in this ancient mortuary chest displayed near the high altar in Winchester Cathedral.

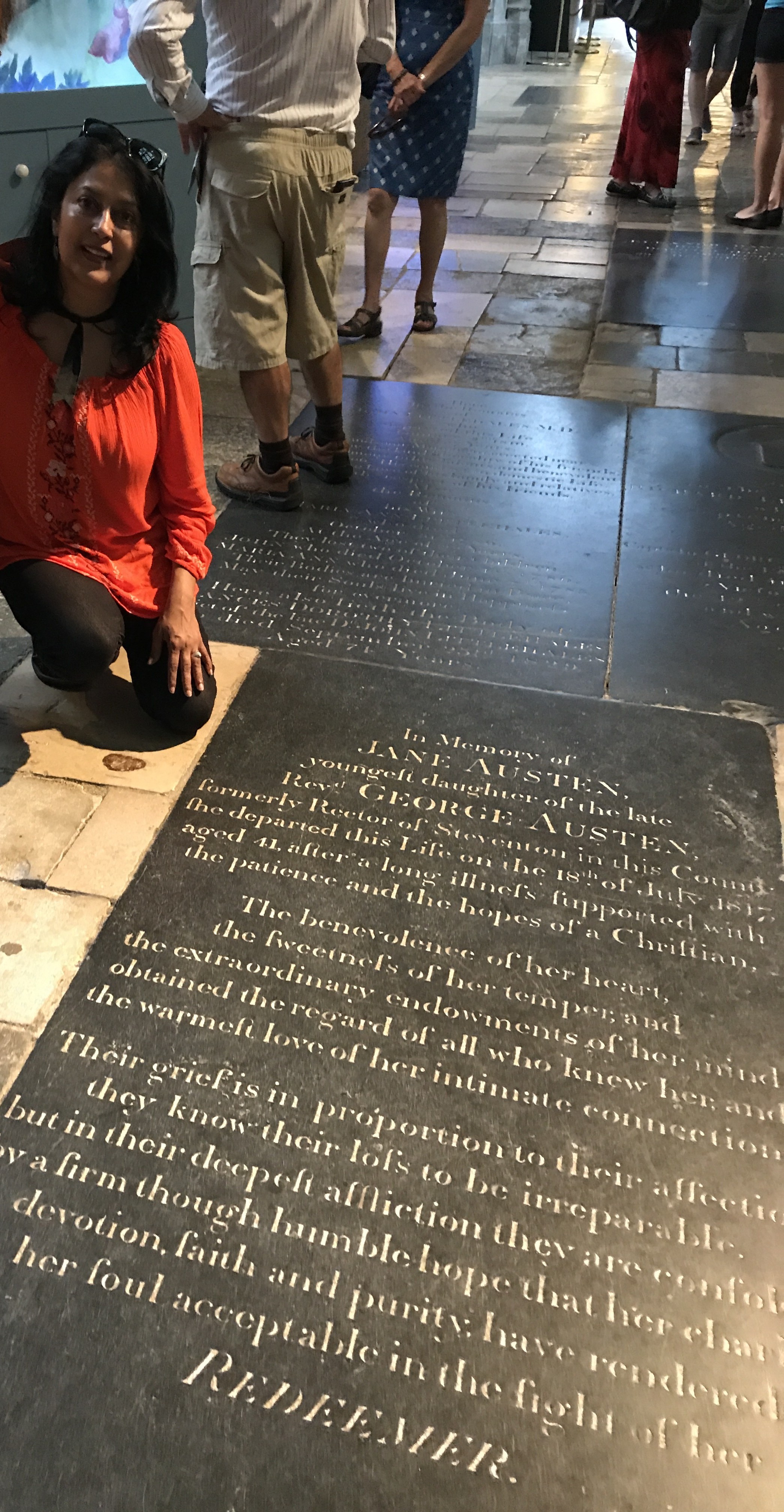

But. But. But. One more reference to Jane Austen. I think the most famous occupant of Winchester Cathedral is Austen, buried in the floor of the north aisle. And we went to visit her grave and pay our respects. And, of course, I wrote a blog post on that—Jane Austen and Winchester Cathedral, Part 1.

Back to Emma’s son, Edward, the king of England, who makes England as French as possible:

Given his childhood history, his long years of residence in Normandy, his fluency with the language, Edward set about appointing Frenchmen in most of the high offices in England. Not just administrative, but also in the church—several bishoprics and church livings went to the Normans, and in time, a Frenchman became Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Norman Conquest of England was well under way.

There was, naturally, some resistance to this foreign influx by powerful Anglo-Saxon earls and thanes, but the king’s men prevailed. Some of the English nobility (we’ll hear of one Goodwine, Earl of Wessex, later in this narrative) fled the country—across the English Channel to Flanders, and to Scotland.

Edward was supposed to have been a very pious, religious man, and he was called Edward the Confessor. We’re right up, in the history, at the very edge of William’s conquest of England. He did not take the country from his uncle, but from another man, Harold—we’ll see who this Harold was, and how he provided yet another excuse for William’s conquest.

The very first scene of the Bayeux Tapestry is King Edward the Confessor (seated, looming large over others) in confabulation with Harold, who would succeed him to the throne of England, before William came roaring in across the English Channel to conquer and change the character of the country. Image Source.

So, even before William the Conqueror took over England, the French, through his uncle, were well-established there.

In Normandy, William was about twenty-three years old, had been ruler since his seventh year, and despite all the foment, had managed to keep the ducal coronet upon his head. One of King Edward the Confessor’s advisors bent to his ear.

Edward had no heirs, no sons, wouldn’t it be a jolly good idea to invite William over to England? And maybe, just maybe, offer him the succession? So that the Anglo-French nobility, newly established, would not lose their standing and their places?

This was in 1051 CE—fifteen years before William conquered England.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Search Engine Keyword Phrases: Norman Conquest; Conquest Normans; Norman Invaders; Norman Invasion; 1066 Norman Conquest; 1066 Norman Invasion; Norman Conquest tapestry; Norman Invasion tapestry; reasons for the norman conquest; what is the norman conquest and why was it important; consequences of the norman conquest; Norman Conquest Bayeux Tapestry; William the Conqueror; William the Conqueror children

Primary Sources: Edward A. Freeman, A Short History of the Norman Conquest of England; John Collingwood Bruce, The Bayeux Tapestry Elucidated; Charles Dawson, ‘The Bayeux Tapestry in the hands of ‘Restorers’ and how it has fared.’ article in The Antiquary; Jacob Abbott, History of William the Conqueror; Dom Bernard de Montfaucon, Les Monuments de la Monarchie Françoise; Hilaire Belloc, The Book of The Bayeux Tapestry.

On the next blog post—William, before the Norman Conquest—his life, his wife, and his children—All Hail William, the New King–The Bayeux Tapestry—Part 2

One Reply to “All Hail William, the New King–The Unsurpassed Bayeux Tapestry–Part 1”