But…not all the credit goes to the Romans, surely:

Before the Romans came to England and built the Roman Baths at Bath, there was good king Lud Hudibras. He ruled over England sometime in the 7th or 8th Century BCE, and had both a great sorrow and a terrible dilemma. His son had leprosy, a devastating disease, with no cure in the times in which he lived. Otherwise, this boy, Bladud, was a fine, stalwart young man, engaging of manner, fine of face and form, a splendid heir to a vast kingdom.

But, Bladud could not live at the English court anymore. Over time, this dreaded illness would eat away at his extremities, turning his hands and feet into stumps, causing everyone to recoil from him in disgust. What sort of a future king would Bladud make?

Lud Hudibras, with a heavy heart, sent his son into exile. His weeping wife, the Queen of England, gave Bladud a gold ring fashioned as two clasped hands, a large one and a small one. I had it made when ye were born. Bring that to me anytime, my son, she said, and I will know it is ye. But, don’t come back until ye are fully cured.

Bladud accepted his father’s dictate and went out wandering into the countryside. The first man he met was a poor shepherd. Bladud exchanged his princely clothing of silks and satins with the shepherd, and went on in his rough and mean sackcloth and tattered coat. He found his way to a village and became an assistant to the local swineherd.

Every morning, he drove his pigs out into the forests where they would chomp peacefully while he prayed for a cure from his leprosy. Instead, his pigs caught the leprosy from him. So, Bladud had to leave his employment with the diseased pigs.

One day, his four-legged companions and he crossed over the River Avon near Bath and to his surprise, the pigs ran squealing and yelping down the valley and plunged into the warm and steaming bog below. They played in that scalding mud, rolled around it in, until Bladud yanked them out of it.

When he washed them later that night, he discovered that their blisters had cleared, leaving pink, happy skin. This happened day after day, and Bladud realized that the bubbling, heated mud of the bog contained curative properties. So, he jumped into it himself and a few weeks later, his skin was clear, gleaming, and healthy. He was cured!

Bladud went back to the court and found his parents, the king and the queen, quite heartlessly in the midst of a feast, the commoners held at bay by a rope fence. He managed to slip under the rope and drop the ring into the queen’s goblet of wine.

When she drank to the end, something clinked in the goblet and she saw the ring. “Where is my son?” she cried out joyfully. And, Bladud, his skin as unblemished as the day he was born, stepped out from the crowd to kneel and kiss his mother’s hand.

General rejoicing abounded at this return of the heir to the throne. After that, either his father Lud Hudibras sent him off to Athens to study for eleven years, or Bladud went himself. He didn’t return to England until his father was dead and then he ascended the throne of England.

It was now Bladud created the city of Bath, made pools of the natural hot springs and opened them to the public so all could profit. The baths were dedicated to the Goddess Minerva and fires were kept burning day and night—when the flames ran low, through the magical powers of the king, they turned into stones and new fires sprang in their place.

During his time in Athens, Bladud had imbibed history and philosophy, and also a fair amount of sorcery. Given that he now had power over a perpetual stone fire, he was convinced he could fly. So, like Icarus, he fixed wings upon his back and launched himself from a cliff. He fell. To his death, dashed into pieces on the earth below.

And…it’s all fiction, this story about the (non) Roman Baths:

It’s a fine story. I’ve had a bit of fun embellishing it myself, rounding out their characters and visualizing the ring that the queen gave to Bladud.

This story appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain. Nominally, our Geoffrey’s giving us an actual history, but he lived in the 10th Century, about eighteen hundred years after Lud Hudibras and Bladud. And, Geoffrey’s entire history has been more or less debunked since the 16th Century.

Besides, some of the names seem made up to me. What do Hudibras or Bladud even mean? It’s almost like Geoffrey, quill perched quivering over sheet of paper was thinking, what shall I name Hudibras’s son? Bladud, said his baby, lying on the hearthrug in front of the fireplace. Bladud, it is! cried Geoffrey.

So, it’s fiction, all of it. Because there’s no actual confirmation that either Bladud or his father existed, or that they ruled over England. But this is the romantic background of the discovery of the mineral hot springs in Bath—prompted, no doubt, by the fact that the baths at Bath would otherwise have been credited to the invading Romans, and not to an English hand on very English soil. Because all the discovered (and existing) remains and antiquities at Bath—coins, altars, steam rooms, saunas, sculptures, temples and inscriptions—date to the Roman era in England.

If not the Romans building the Roman Baths…who then?

There’s little tangible evidence that the people of England enjoyed the benefit of Bath’s waters until the Romans came. Which is not to say they didn’t.

And, the-temple-dedicated-to-Minerva legend persists, in a somewhat convoluted way; even if Bladud didn’t build the temple, the theory goes that the Celts did and dedicated it to their goddess, Sulis. When the Romans came and began their building, they regarded Sulis as Minerva, and for a long while, called the town of Bath as Aquae Sulis, the waters of Sulis.

So there. The Celts discovered Bath before the Romans did. And the Roman goddess Minerva is actually Bladud’s Minerva, but she’s also the Celts’ Sulis. Got all that? As I said, convoluted a bit.

However, just to add to the confusion, here’s another theory about the sequence of events. Bladud has been debunked. But, it’s also likely that the Celtic Druids discovered these wondrous warm waters erupting from the earth at a constant temperature (by magic, it is said) and built a temple over the springs to their goddess Sulis. That goddess Sulis was identified by the Romans as their goddess Minerva—and they merely continued the Celt tradition.

Bathing Beauties:

The Romans must have been a very clean people. If you’ve read the Asterix and Obelix comics, there’s one in which the British (fighting the Gauls) stop their battles at 4 o’clock exactly, because it’s tea time. (A spot of milk for your tea, old chap? Thank you, don’t mind if I do).

I’m guessing the Romans went home at dusk from the battlefield and bathed. From the evidence of the baths at Bath, the Romans obviously loved their baths!

The Romans probably discovered Bath and its beauties during the reign of Nero, around 50 CE. They built the baths and their temple to Minerva, with its perpetual fire in front of the altar. That fire, much like our fictional king, Bladud’s fire (who predated the Romans by a good eight hundred years or so) was kept alive day and night, and when the fire burned down, it left a sediment of stones, just like Bladud’s fire.

There’s an easy enough explanation for this. The coal that kept the fire going constantly was dug up from three miles outside Bath at Newton. And when this almost powdery Newton coal burned down, it calcified into rocks.

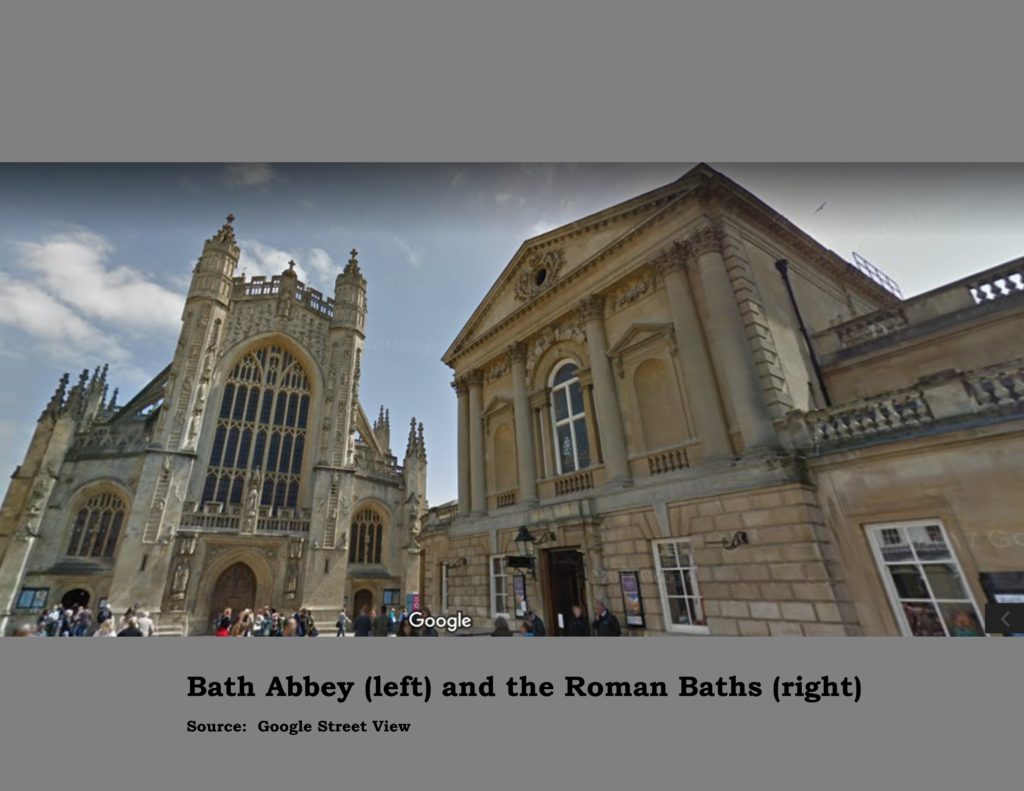

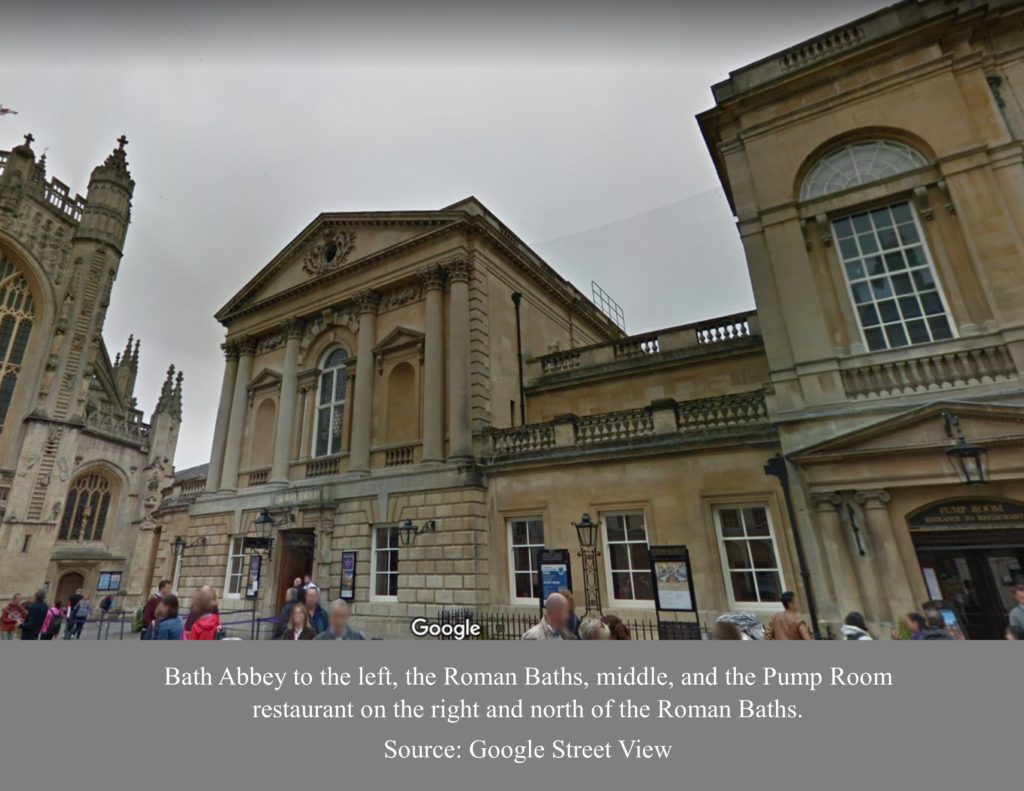

This temple to Minerva doesn’t exist in modern day Bath. But, Bath Abbey does, incredibly close to the Roman Baths. Both face the same courtyard, and are literally that proverbial spitting distance from each other.

In talking of the Roman baths at Bath, ancient writers also always mentioned the Minerva temple, almost as in, it was that close by. Which has led to the speculation that Bath Abbey must sit today on the ancient site of the temple to Minerva. But, the current plan of the Roman Baths shows that the temple was situated north of the Great Bath. So, it is the Pump Room restaurant that is directly above the ruins of the Minerva temple.

What’s in a name?

For a while there, no one was sure if Bath was called Aquae Solis or Aqaue Sulis. Solis is the sun, and Sulis is Minerva. Was the town called ‘waters of the sun,’ or ‘waters of Minerva?’

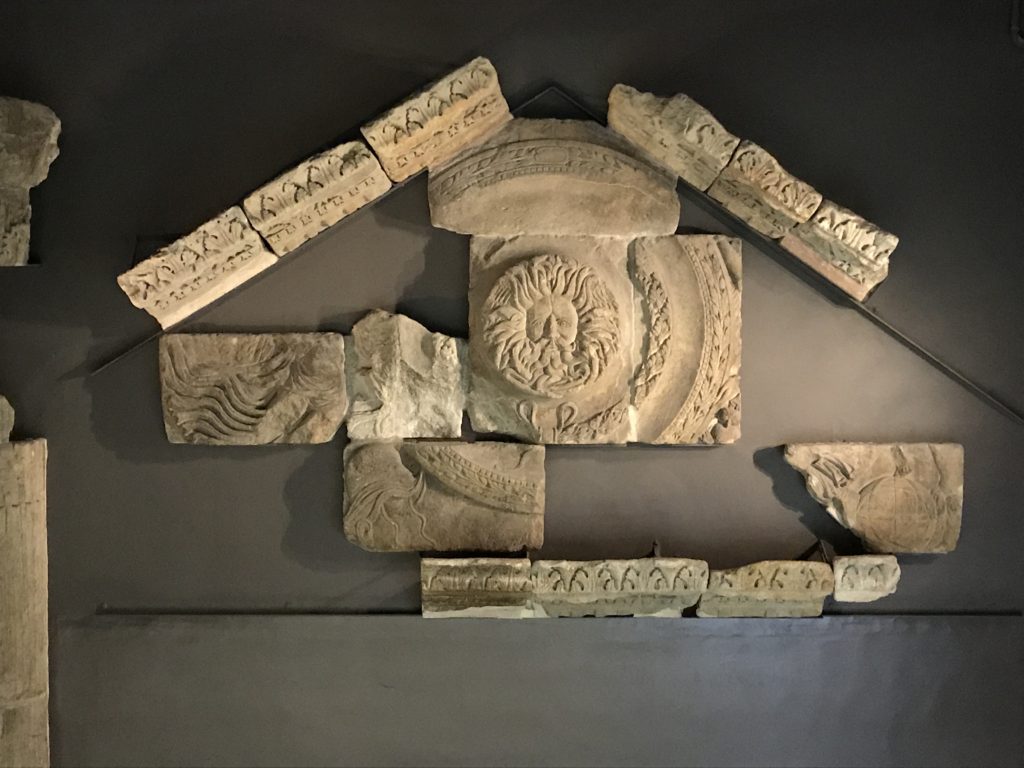

The discovery of the remains of the temple within the Roman Baths complex put that academic debate to rest. The temple was dedicated to Minerva, also the goddess Sulis, so the Romans must have called Bath after her.

By the nineteenth century, Bath was established as a meeting place for the swanks. Jane Austen set parts of her novels there; she lived in Bath for a few years and knew it to be a buzzing, humming, matrimonial market. (I’ve written several blog posts on Austen; the links should take you to the first parts and you can jump to the subsequent ones from there–Steventon Part 1; Chawton Cottage Part 1 and Winchester Cathedral Part 1). The eligibles spent their days in the pump rooms, and nights at the theatre or the various balls and dances held around the town. Hunting. Hunting. Everyone came for the benefit of the waters, ostensibly, but benefitted in other ways.

At the pump rooms, people faithfully drank glasses of the mineral waters for a cure, for gout, for a migraine, for their overall health. When the waters really did not effect those major cures that had been promised, historians then went back to the Bladud legend (see, even discredited, Bladud keeps coming back into the history) and said that if Bladud’s pigs had indeed been cured, then the pigs had benefited much more from the mud they had wallowed in, than the actual waters.

So, bathing in just the mineral waters in the Roman Baths, or drinking those waters, was not particularly helpful—especially cleaned of the mud and piped into Bath all sparkly and pure!

The Roman Baths vanish…for a while:

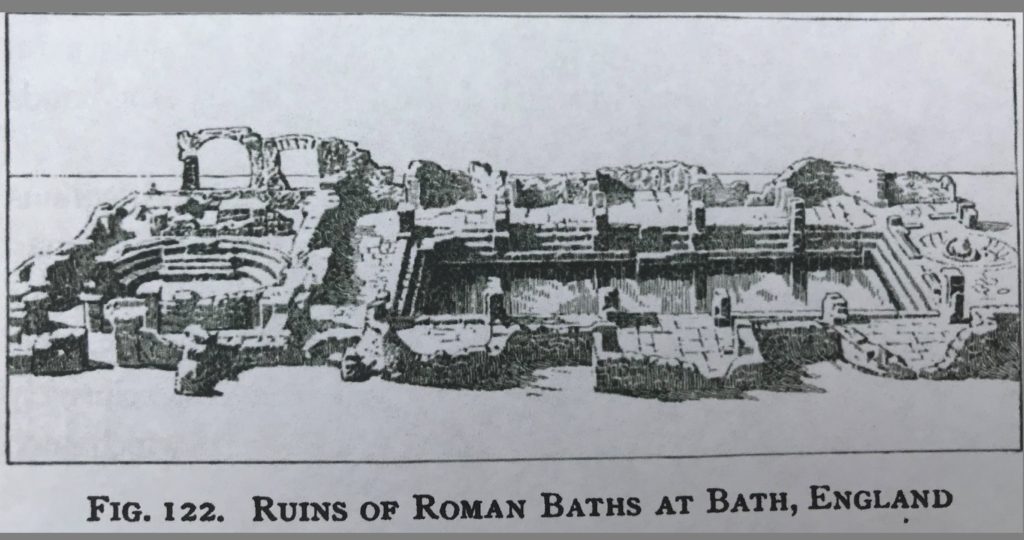

Although we now date the Great Bath, the other hot and cold pools, the saunas, and the temple courtyard to the Romans in Britain, the Roman Baths were only discovered in 1755. No one’s really sure when the Roman Baths disappeared from the narrative and written history at Bath.

But the Romans left England in the 5th Century and were presumably using the baths until then, and then there was the roil and toil of infighting in the country and the Saxons were invited in. By the time the Saxons took over—it was not they who destroyed all, but only some of the evidences of the baths—the infighting had laid several layers of earth and mud over the Roman buildings. This is known because the 1755 excavation also brought up Saxon graves, buried well above the Baths.

Source: Outlines of European History by James Henry Breasted. 1914.

Bath was a fairly big Roman stronghold, with all the main buildings (downtown, if you will) grouped around the source of the mineral springs. There were the Roman Baths, and the temple of Minerva, and, as another speculation, that the site where Bath Abbey stands today was occupied then by the Basilika, the temple of Diana. Tales of miraculous cures brought Romans from all over the country to Bath, and presumably Romans from Londonium—a hundred and fifteen miles away—to taste the waters, to bathe in them.

Two legions of Roman soldiers were quartered in Bath, so it was a well-populated town. The principal street ran north from the Baths, a hundred feet wide to accommodate horse chariots in each direction. The Romans were supposedly either kindly rulers of the English, or they had conspired to rule over the English by providing them with baths and massages to lull them into a contented state of slavery!

After a four-century rule, the Romans left England. An unsettled period followed, during which the Saxons invaded England. When they set up their camp outside Bath to besiege it, King Arthur (yup, he of the Round Table) defended the city. It was but a temporary respite. In 577 A.D. the Saxon chieftain Ceaulin took Bath.

The Saxons destroyed what little remained of the Roman altars, temples, pillars and buildings, and renamed the city from its elegant Aquae Solis (or Sulis) to a more appropriate but coarse ‘Hot Bathum.’ The Saxons then established a nunnery, converted that into a monastery, and then a church which eventually became Bath Abbey. (More on this on the blog posts on Bath Abbey; Part 1 here and Part 2 here). All the while, the Roman Baths slumbered so close to the monastery/church/abbey, underground and undiscovered.

At Bath Abbey the priests built their own baths, some public, some private, and despite all the digging and construction so close to the source of the mineral springs, they still didn’t find the actual Roman Baths.

The Abbey priests used the baths mostly for recreational purposes. Even in Roman times, there’s little mention of their medicinal or curative properties, and scant mention during Saxon or Norman times. Either the population was relatively healthy, or bathing in the waters kept them healthy. The Bladud legend—the cure of leprosy—didn’t exist before Geoffrey’s 10th Century History and then, it more or less died down.

Not so by Shakespeare’s time. A book published in the 16th Century mentions the baths—but not, presumably the Roman Baths which had not yet been discovered yet—instead, a Crosse Bath which was a large pool with a cross in the center used mostly by leprosy patients hoping for a cure; and a larger, and hotter, Common Bath; and a King’s Bath which was the largest, and closest to Bath Abbey.

The waters in all the baths were a deep blue and ‘reeketh’ with a sulfurous smell and taste. At noon and at midnight, with clockwork precision, the waters in all the baths were too hot to wade into, and so the baths were shut from half past ten until half past one, morning and night. Presumably, they were open the rest of the time.

And then, in the mid-1700s, the Roman Baths were discovered, along with an entire Roman city that had slumbered for some thousand years. And that is what we will visit in the next blog post.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next blog post—Healing Waters—The Roman Baths at Bath—Part 2—what they were, and what they are today.

4 Replies to “The Roman Baths at Bath–Healing Waters—Part 1”