We blew into Winchester Cathedral at the end of a very long day, and I use that verb advisedly. We had spent the morning and afternoon in Austen country—Steventon where she grew up, and the St. Nicholas Parish Church (Part 1 and Part 2 on the blog) and Chawton Cottage (Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3) where I wandered around for far too long. So, by the time we got to Winchester Cathedral, there was, it seemed, just a teacup full of time left before the church closed for the day.

But, stepping inside was into a sea of calm. I paid my respects at the grave, and still had time to walk around the cathedral, breathe the air, and dwell on its history. And while Jane Austen is arguably its most important occupant, Winchester Cathedral was there for many centuries before her, and its mellow stones are steeped in legend…and some myth. Read on.

The Somewhat Origins of Winchester Cathedral: Good King Lucius was kind to his people, attentive to their needs, scrupulous in insisting that the meat from the hunts be distributed carefully, and that the old and the very young be taken care of. And, he was a bold and a brave warrior, not afraid to protect his borders and to command his army against the Roman invaders. But, something was missing from the king’s life. A purpose. A devotion. A belief.

Then came news from across the great waters of common men, who through the power of their faith in Christianity, performed miracles of healing. Lucius listened to these wondrous tales, and wrote to the Bishop of Rome, Eleutherius, asking to be converted. The Bishop agreed, and sent two missionaries to the court of Lucius. He was baptized, and soon, his people took on this new religion and it spread all through Britain. Lucius then founded some of the earliest churches in the country.

Or so the legend goes.

But Lucius, credited with bringing Christianity to Britain…did not exist at all. And since he didn’t, I added a bit of fiction myself—all that about him being good, kind, missing something in his life. Makes for a good story, I thought.

Even as fictional a Lucius is, as time went on, ‘histories’ of Britain embellished on this contact between Eleutherius and Lucius and added their own details. The best explanation for this centuries long ‘fake news,’ is that it filled in a ‘pious history.’

So, let’s get this clear. Lucius did not exist. The stories about him are untrue. But, a stained glass window in York Minster celebrates King Lucius, and gives him a face. It’s a powerful mythology.

center. How can you argue when presented

with an actual image? Source.

The imaginary Lucius was said to have been the founder of the old church, Old Minster, at Winchester. But, the Old Minster has been dated to the 7th Century, about 500 years after Lucius, well, didn’t exist. In the 9th Century, the Old Minster got a competing church, New Minster, built alongside—so close, it is said, that the chanting monks’ voices battled each other.

Today, neither Lucius, the Old, nor the New Minster exist. Instead, just a little north of the site of the Old Minster is the cathedral of Winchester. Which was first constructed beginning in 1079 by Bishop Walkelin. This was at the beginning of Norman rule in England.

William the Conqueror and the Normans in England: Winchester Cathedral was begun after the Norman conquest of England—important enough, because a lot of contemporary churches and buildings in England date to this time period, either in whole or in part (that is, the contemporary buildings retain a part of the Norman buildings, or have been remodeled on early Norman buildings).

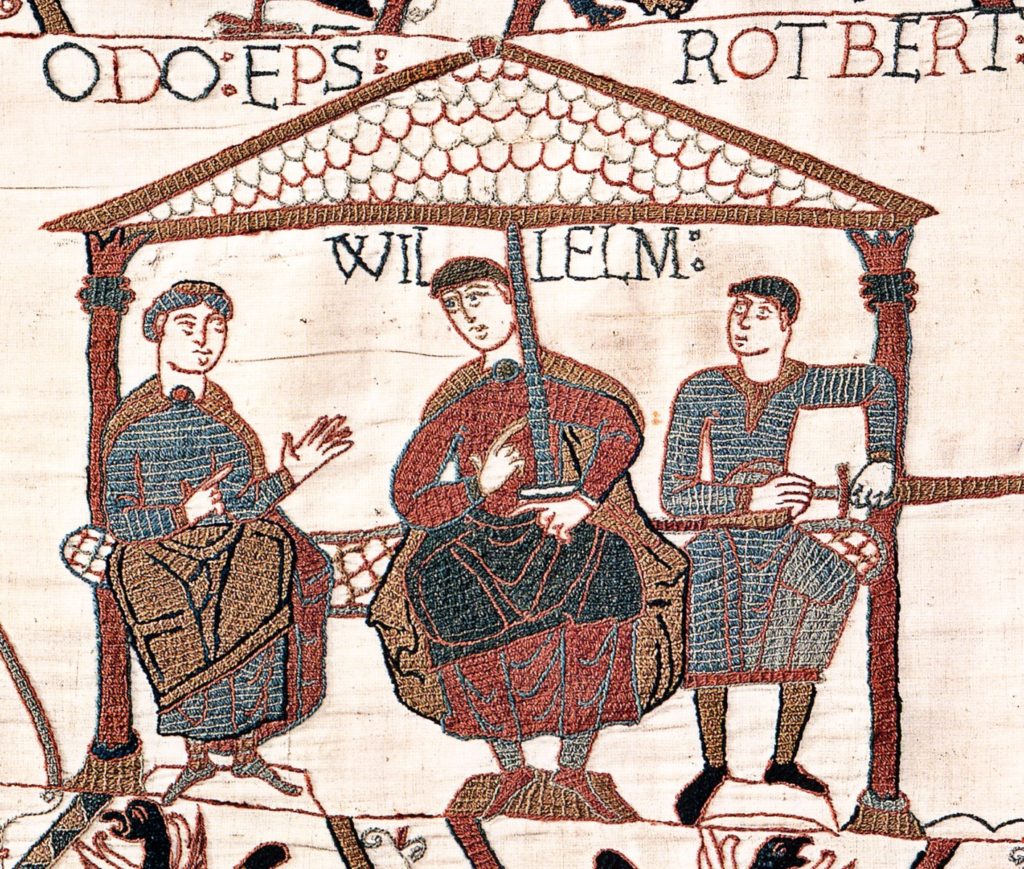

In 1066 A.D., the English king Edward the Confessor died. He had no children, and had held out a slight promise to William, the Duke of Normandy (northwest France) that William should be heir. Edward and William were related, of course. Upon Edward’s death, however, his brother-in-law Harold seized the throne of England. By September of 1066, while Harold was off fighting elsewhere, William landed in England to lay claim on the throne of England, and successfully defeated Harold.

And, a new era begins: It wasn’t a minor invasion of England. By 1072 A.D., William had put down all rebellions and claimed all the land as his. The Norman army he brought over became the new English aristocracy. The language of the courts became something called Anglo-Norman, a mixture of French and English. It is said William never learned English at all, and most people became bilingual. Englishwomen were forced into marriage with the Normans—perhaps as a necessity, since the old English nobles had fled the country. And, William ruled over them, iron fist and all.

He allowed the aristocrats a feudal tenure, whereby they ‘owned’ land only at the mercy of the king, in return for providing armies to him, or taxes from their tenants and treasuries. (This last part about the feudal tenure is how the Mughal kings ruled India also from the 16th Century onwards. This was called the ‘law of escheat;’ the Mughal king was proprietor of all lands. The nobility were given ranks called mansabs which determined how much land they held, and what service they gave to the king in exchange. In Mughal India, when the amir died, by law, the lands went back to the king, and he would cast an eye over the property, and another eye over the heirs and, if they were loyal enough to him, he’d give them their father’s property back. Temporarily, of course.)

around the time of William’s conquest of England, 1070 A.D., perhaps. Source.

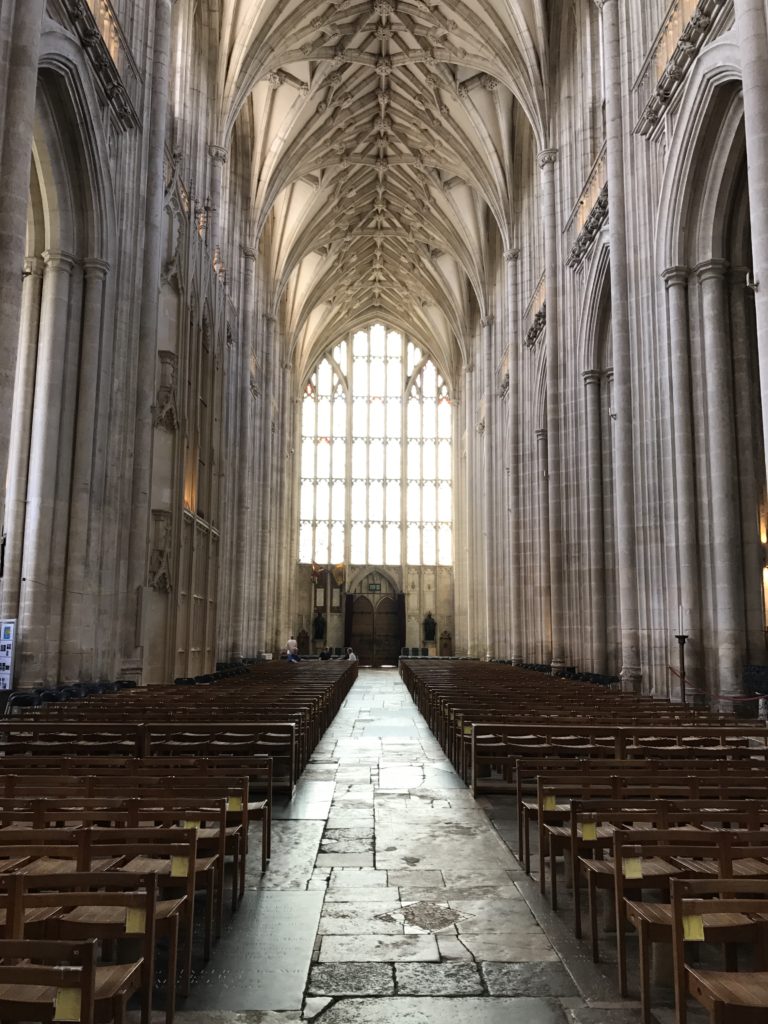

Religion changed also; now the high offices of the land were in the hands of those loyal to the new king of England, William the Conqueror. He began building the Tower of London. In 1079, Winchester Cathedral was built by one Bishop Wakelin, who was William’s cousin and had been his royal chaplain. Some of what Wakelin built still remains in Winchester Cathedral, notably, the long nave, the crypts and the transepts. The original tower over the transepts fell in 1107, and was rebuilt to what it is today, shorter than the towers on most other English cathedrals.

Henry de Blois, his king Henry II, and his friend Thomas: In 1129, Henry de Blois became Bishop of Winchester, under the auspices of King Henry I, his uncle. A few years later, his brother, Stephen de Blois became king. This Henry de Blois was an architect, credited with planning and designing hundreds of English villages and canals, and several castles. Whatever he might have contributed to the architecture of Winchester Cathedral, there still exists one item he gifted/brought to the cathedral. The massive, and gorgeous, Tournai font with scenes from the life of St. Nicholas of Myra.

The font was constructed and carved in the Belgian town of Tournai, its blue-black limestone quarried from a seam near the River Scheldt, and made by local masons. This work was mostly done in the 12th and 13th Centuries in Tournai, and most of the existing fonts—of which the Winchester Cathedral font is the most famous in England—date to that time period.

Henry de Blois also, interestingly, intersects with one of the subjects of a blog post I’m going to write on Canterbury Cathedral. It is said Henry originally wanted to be Archbishop of Canterbury, but couldn’t get the job. However, when his brother, Stephen, became king of England, he made Henry papal legate, which put Henry in a higher office than the Archbishop of Canterbury (otherwise the highest cleric in the Church of England). When King Stephen died, Henry II became king of England. Under this new king, Henry de Blois and other bishops consecrated Thomas à Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury. Then, Becket angered Henry II, who put Becket on trial for treason against his king, and the man who presided over the trial was Henry de Blois, Bishop of Winchester. Later, Henry II had Becket killed in Canterbury Cathedral, and then hugely repented, and so we went to visit Canterbury. That story (about Becket) and Canterbury Cathedral, on a future blog post.

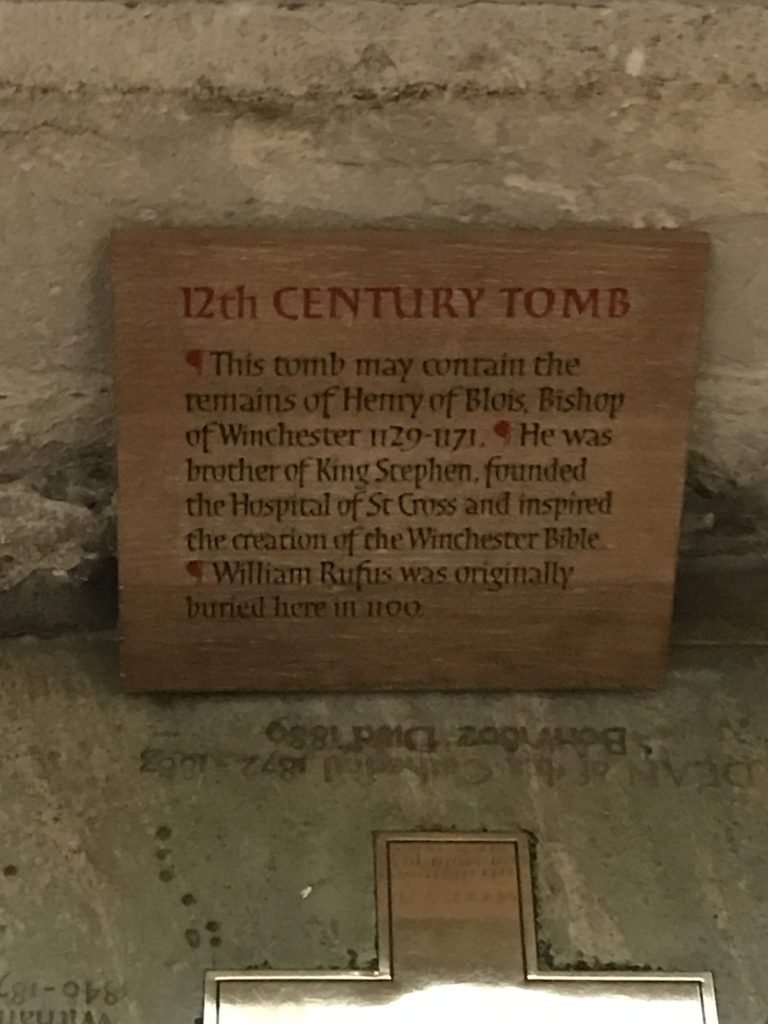

Henry de Blois is speculated to be buried in the choir at Winchester Cathedral. There’s a tomb there, which ‘may contain’ his remains. It’s the part of the church over which the tower rises, and the original tower collapsed in 1107 over this tomb. At that time, it was identified to be the tomb of King William Rufus. Now, Rufus was supposedly a hard-swearing, crass man with no social manners, much disliked by everyone, and the tower falling (even though it didn’t damage the tomb) was supposed to be a sign of the wrath of God on Red Rufus (he had red hair supposedly). Obviously, something’s changed since, some new discovery made, because that tomb in the center of the choir is no longer Rufus, but ‘may contain’ Henry de Blois.

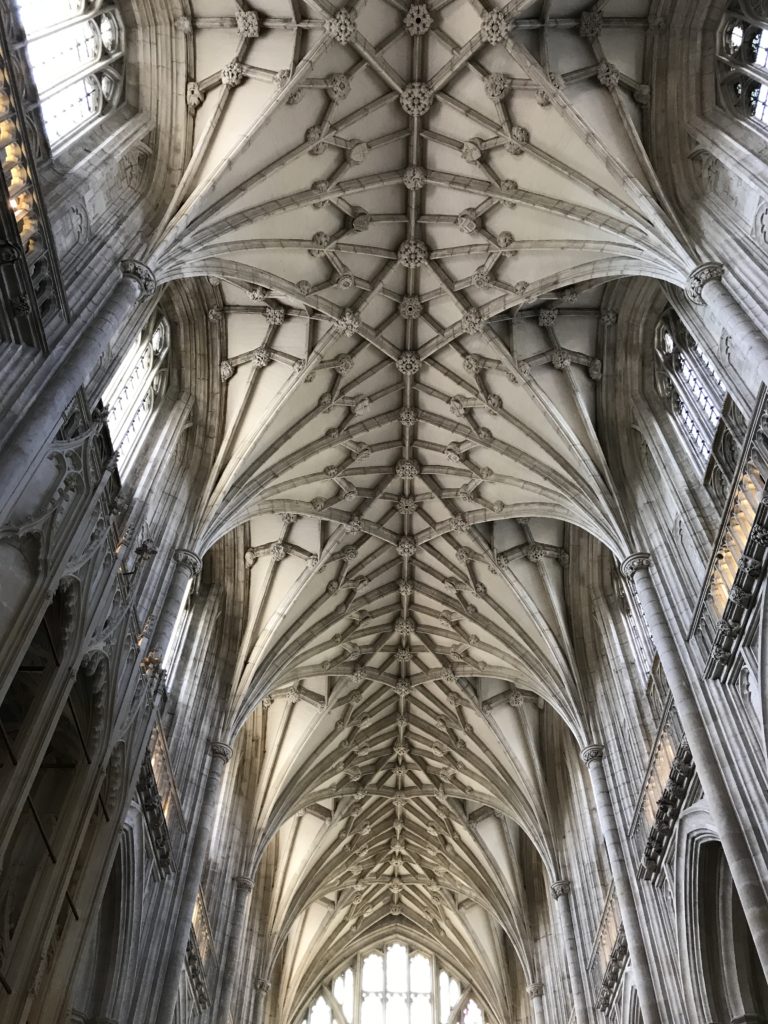

The Cathedral itself: Built up over the next few centuries, Winchester Cathedral today is a serene and lofty structure, filled with history and some spectacular architecture. The ceiling of the nave is carved in that limestone quarried from Bishop Wakelin’s property in the Isle of Wight.

The choir stalls , built of Norwegian oak, date to 1296. The arches were redone in the fourteenth century and the screens behind were put in by Bishop Fox in 1525.

Richard Fox was bishop of Winchester under King Henry VIII—that same king who broke from the Roman Catholic Church and created the now Church of England. Like many of the other bishops (in most of the other cathedrals also), Fox dedicated a space for himself within the cathedral once he died. A chantry chapel, it’s called. A chantry is a set of masses sung for the departed soul, to speed him or her toward heaven. Bishop Fox’s chantry chapel is the place where these masses take place, and it’s traditional for the person for whom the chapel is named to pay for its construction and for the priest whose duty it is to sing the mass.

The reredos of the high altar is a magnificent screen reaching the ceiling, with a cross in the center flanked by statues, all made in stone. The original reredos was constructed in the first half of the fifteenth century by Cardinal Beaufort. However, “In 1538, it was despoiled of its images.” It’s a somewhat bare statement. But, look at history and you see that Henry VIII was king then. And, he wanted to divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry Anne Boleyn. The pope said no. Henry threw a fit and in 1534, broke from the Roman Catholic Church and made England Protestant. Over the next few years, all English churches were expected to bow down to this new religion of their king’s choosing, and those which didn’t were damaged. It’s quite possible, since the timing fits, that this ‘despoiling’ of the high altar screen took place because someone in Winchester Cathedral refused to obey the king.

The reredos was then painstakingly restored. The central cross had withstood the despoiling, but all the other niches had to be filled. And, as you will see it today, it was redone with statues of the patron saints of the cathedral, St. Paul and St. Peter, the Virgin Mary, St. John, and the Archangels Gabriel, Michael, Raphael and Uriel, along with various bishops.

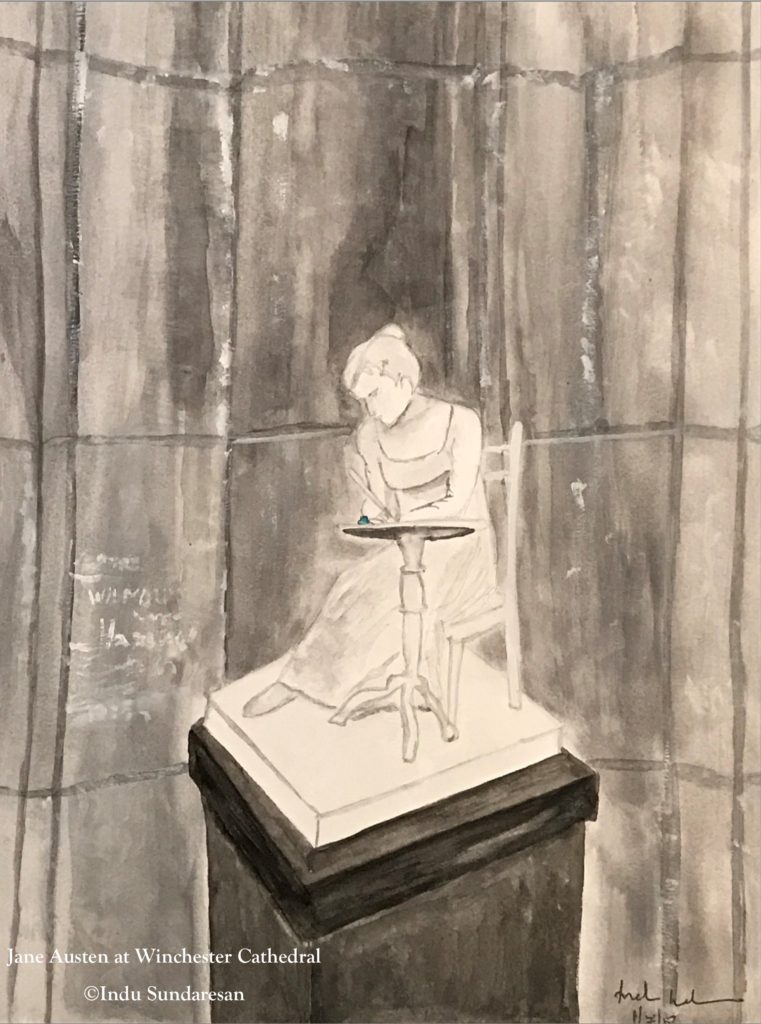

I’m glad we visited Winchester Cathedral. But, we went there exclusively because it’s the final resting place of one of the best and most famous authors in the world, Jane Austen. And, we’re going back to the year 1817 to follow Austen to Winchester and into the cathedral.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—Jane Austen’s final years—coming to Winchester—buried in the Cathedral—Now I lay me down to sleep—Jane Austen and Winchester Cathedral—Part 2

3 Replies to “Now I lay me down to sleep—Jane Austen and Winchester Cathedral—Part 1”