We just left the thriving Chola dynasty of ancient India extinguished at the end of the 4th Century CE. All of a sudden, and with no seeming explanation.

And then, for three centuries there was nothing out of southern India. It was as though entire existence had been wiped out. Because there’s nothing to tell us of which dynasties ruled, who they fought, who they married, what they built, or whom they patronized.

By the 6th Century, one of the other kingdoms of ancient India (who had ruled alongside the Early Cholas) emerged in power, along with another two.

And, still, no Cholas.

The Cholas of ancient India (?) come back, with a whimper for now:

And then, one little tantalizing trickle of information emerges: Vijayalaya Chola captures Tanjore about 850 CE.

That’s it. Who was he? Was he descended from our Early Cholas? If yes, where had they been for five centuries?

Nobody knows.

Historians speculate that he was a feudatory chieftain of one of the three then-ruling dynasties, the Pallavas, who were in constant conflict with the other two—the Chalukyas, and the revived-from-ancient-India Pandyas.

As these three rulers regularly combated each other to maintain their fluid boundaries, perhaps when Vijayalaya Chola took over the city of Tanjore, he was acting on behalf of his feudal lord, a Pallava king?

Questions abound, of course. Had Tanjore belonged to the Pallava and been taken by the Pandya? Or had someone else taken it? Or had it originally belonged to the Pandya, and the Pallava sent the Chola to take it?

Whatever the actual history, Vijayalaya Chola—who certainly had no right to the spoils of a war he was fighting on behalf of his sovereign (the Pallava)—captured/recaptured Tanjore and…well, he declared himself king.

Make a note of Tanjore, because it then became the capital city of these Later Cholas.

(The Early Cholas in Part 1 and Part 2 were established at a port city called Kaveripattinam, and they ruled from there. Obviously, during the five centuries when no historical account of them exists, they lost that capital.)

As you drive up to the Airavateshwar Temple, you first see the walls surrounding the courtyard, and the glimpse of the vimanam, the tower over the inner sanctum. Astride the walls are statues of Nandi, Shiva’s bull.

So now, here is our Vijaylaya Chola, holding on fast to Tanjore, and naturally, he was not to have it easy.

It was a while before the Pallavas could bestow their attention upon this infraction, but they did eventually turn in battle toward Vijayalaya the usurper. Simply put, they were defeated, and Vijayalaya set about cementing Chola power in south India again—and here, began the Later Chola empire.

A good thing it was too, because three magnificent temples that you can visit today come from these Later Cholas.

The first is the so called ‘Big’ Temple at Tanjore (very appropriately named actually, you’ll see why when we visit there); the second, forty kilometers northeast at Kumbakonam, (the Airavateshwar Temple we are now going to visit); and a third, another forty kilometers northeast of Kumbakonam.

However, I’m going to zip through these Later Cholas…

…until we get to the man who built the Airavateshwar Temple in Darasuram, Kumbakonam, for two reasons.

One, despite the five-hundred-year (or so) gap between the two Chola dynasties, there would not have been much difference in the basic elements of their lives. The same wars (different dynastic enemies to be sure); the same entertainments; the same charities; the same duties and responsibilities. Again, I’ve talked extensively about all this in Parts 1 and 2.

And two, on a future blog post, we will visit the grand temple at Tanjore, and there I will slow down in recounting the story of these Later Cholas.

The first and most prominent king to appear in this new storyline is Rajaraja Chola I. This was a century and a half after Vijayalaya re-launched Chola supremacy.

Rajaraja I was a younger son, and his path to the throne was long and complicated–some infighting and a murder of a Yuvaraja (the crown prince), exciting stuff! Upon ascending, however, he set out to conquer and to defend, amassing territories in northern Sri Lanka, some of the Maldives Islands, and some of the other kingdoms in south India.

If this new Chola power had been shaky for a while, under his rule it was secured. He built the fabulous and gigantic temple at Tanjore, which will come up in a future blog post, and so I will not dwell upon him now.

Rajaraja Chola I’s mammoth temple at Tanjore. Source

After another century and a half, during which time the direct Chola line of descent flickered out, a king laid claim to the throne whose mother was a Chola princess. King Rajaraja Chola II (the builder of the Airavateshwar Temple) is descended from this maternal line, and by the time he came to rule in 1143 CE, the Cholas were comfortably in control of a vast amount of southern India.

But…the Later Cholas are already destined to obscurity?

Rajaraja Chola II had a somewhat placid reign, and began constructing the Airavateshwar temple toward the end of it.

He was a benevolent and altruistic ruler, donated vast amounts of money for the maintenance of other temples and charities, and, having no heir, sensibly—and with forethought—designated one from another maternal line.

The extent of Rajaraja Chola II’s territories during his rule. Source

And yet, his reign was the beginning of the end of this Later Chola dynasty.

The man for whom he was named, Rajaraja Chola I (who had ruled some hundred and fifty years before our Airavateshwar builder) had set the Chola dynasty firmly on the map, much as his ancient India predecessor of the Early Cholas, King Karikala, had done (see Parts 1 and 2).

Turns out, the name is about the only thing Rajaraja II (our builder) had in common with Rajaraja I.

Somewhere along the line, after stamping their might upon history, these Later Cholas had become complacent. And Rajaraja II was not as…fierce, or territorial, or aggressive as the other kings of his dynasty had been.

While the Early Cholas disappeared from historical narrative around the 4th Century with an abruptness and lack of reason which is astounding, historians pinpoint to our builder’s rule as the turning point at which the Later Cholas fell to the same fate.

Even during Rajaraja II’s rule, the outer edges of his kingdom began to fritter away; within, his central administration weakened, and his alliances with neighboring kingdoms deteriorated.

An immediate effect was that his successor was forced to involve himself in a civil war in the Pandya kingdom, taking one side, while the other was supported by a Sri Lankan ruler—thereby gaining him the enmity of both the (opposing) Pandya and the Sinhalese.

Our Later Chola founder, Vijayalaya Chola, built this temple in Puddukotai in Tamilnadu. By this time, the Pallava kings had already employed, to great effect, stone and granite in their temples, and the Chola king borrowed their architecture to create this earliest example of the Later Chola period.

A century and a half later, his great-great-great grandson Rajaraja Chola I would build a gigantic stone temple in Tanjore, and another century and a half later, Rajaraja Chola II would build the Airavateshwar temple. Source

However, it was while things were still going swimmingly that Rajaraja II embarked on his Airavateshwar Temple.

Brick or stone?

The brick-and-mortar temples of the Early Cholas, five hundred years ago, had long been surpassed by building in the stone and granite of the country.

The Pallavas, in the 7th Century or so, had built their seven stone temples at Mahabalipuram just south of the Chennai. The Later Cholas used the same material in their other two splendid temples and the art of carving and sculpting in stone had become a fine and refined skill by the time Rajaraja II came to construct the Airavateshwar Temple.

And, he built it much along the same lines as the earlier temples of the Later Cholas—in a large scale, an expansive complex, with several imposing gopurams.

Today, however, the Airavateshwar temple grounds are much constricted—mostly to a wall surrounding the great shrine to Lord Shiva, an adjacent shrine to His consort, Parvati, in a separate enclosure north of the main shrine, and a pond. The pond, the water tank that gave the temple its name and fame.

An aerial view of the Airavateshwar temple complex today. The main shrine is below, the Parvati shrine just north, and to the east is the temple pond. All these would have been part of a larger structure with more temples, and streets within. Source: Google Maps

We went to visit the Airavateshwar temple towards noon, after having been to four other temples in the Kumbakonam area. Within that city, so numerously populated with places of worship, one temple wall almost seems to share its height with another—they are so closely stacked.

The Airavateshwar temple is outside town, a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is within a sward of green lawn, and as you approach, you see the vimanam—the tower built on the main shrine—rise magnificently over the walls.

Sitting in repose on top of the walls are identical statues of Nandi, who is Lord Shiva’s sacred bull, his mount. Most Hindu gods have their mounts. Shiva’s son Murugan’s mount is the peacock; his second son Ganesha’s mount is the mouse.

Every Shiva temple will have a Nandi, typically facing the deity. And several temples have Nandis around the complex–here in Airavateshwar, of course, the Nandis are on the walls also; a first indication to a pilgrim that this is, indeed, a Shiva temple.

What does the water tank have to do with the name of the temple?

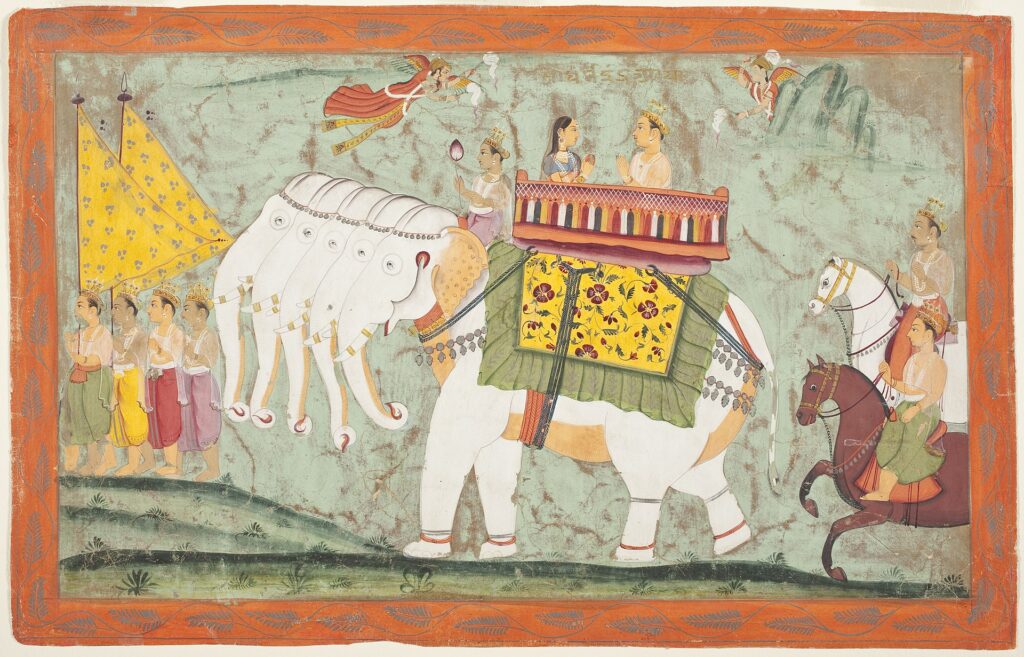

Since we’re visiting the Airavateshwar temple, here’s a good time to remind you that this Lord Shiva is called Airavateshwar—in other words, Airavatam’s Eashwar, or, Airavatam’s god.

Airavatam, the elephant, was Indra’s mount—and Indra is the king of Gods.

The elephant, suffering in sin and in body, came here to bathe in the water tank, to purify his soul and regain his milk-white color. And because Airavatam prayed to this Lord Shiva and was cured, this Lord Shiva is called Airavateshwar.

Here is Airavatam, carrying his lord and master, Indra, and his consort, Shachi. Source

As an aside, the Tanjore/Kumbakonam area is rife with Shiva temples because the cities are of great antiquity, well-established in ancient India. Also, mostly Shiva temples because the Chola kings were Shaivites–followers of Lord Shiva.

Thankfully, however, every temple has a legend, and, a name from that legend to distinguish it from the hundreds of others.

Else, how was anyone to give directions? The second street from the Shiva temple. Er…which Shiva temple? Now, if I were to say, the Airavateshwar Temple, you’d know exactly which Shiva temple to head toward!

But…who built the temple?

The temple’s tank, the pond I mentioned above, was said to have been formed when Lord Shiva flung his trident into the earth and water gushed out. So, the waters had magical and therapeutic properties.

Well before Airavatam came to Darasuram, Yama, Lord of Death, who had angered a sage, went on a pilgrimage hoping to ease the burning sensation on his skin. He prayed at the Darasuram water tank, bathed it in, much like Airavatam, and was healed.

In grateful thanks, he built the temple to Lord Shiva.

Presumably since Lord Yama could not spend all his time at Darasuram, he decreed that those who managed the temple would become kings, and those who bathed in the tank—called Yama Tirtham; Yama’s tank—would be cleansed, not just of their bodily ailments, but also their sins.

Myth aside…

…King Rajaraja Chola II is considered to be the actual architect of the temple. Well, patron anyhow.

Directly in front, and at a short distance of the temple’s gopuram—the entrance tower—are the remains of another gopuram. The temple at Tanjore has two entrance gopurams also, and it was built well before this Airavateshwar temple, and so the form and structure was likely copied here.

This is the preserved gopuram—the actual entrance into the temple. It faces east, as do entrances to all Hindu temples. Further east (to the right in the first and second picture) across a patch of lawn, you can just about see the ruins of the other gopuram. (The ruined gopuram is the third picture.)

This entrance gopuram is a few steps down from ground level as you approach the temple. And within, in front of the gopuram are two other miniature temples, situated back-to-back.

Within the sunken courtyard, what you see at the very back is the entrance gopuram into the temple. Directly in front, the tiny stone platform (under the tiny stone canopy) is the Bali Peetham, with a statue of Lord Ganesha. Behind this, facing the entrance gopuram is a statue of Nandi.

The Bali Peetham—the sacrificial stone—was used for just that in ancient India, quite possibly for the sacrifice of small animals. Today, worshippers place offerings of fruit and flowers for the Gods here.

Or perhaps it’s not even the place that requires the slaughter of another living being.

Situated as it is, in the front of the temple entrance, the Bali Peetham is where you are to leave (sacrifice) your ego, and your pride and arrogance, so that you can enter God’s house with an open soul, humble and respectful.

The sunken courtyard in front of the entrance gopuram. Here, you see the back-to-back shrines more clearly. Nandi, facing the entrance and the deity, and the Ganesha shrine and the Singing Steps on the right.

At Airavateshwar, there are a series of stone steps on southern side of the Bali Peetham, enclosed now by an rusty iron railing so that no one can run up and down the steps.

That was a thing, though, that flit on the steps, because the sound of your feet flapping on the stone would cause a certain music. And so the steps are called the Singing Steps. With the iron railing guarding them, to preserve them, the steps are silent today.

God’s influence begins at the entrance:

God’s power is concentrated in various spots within the temple. In the main shrine, as a matter of course, where the presiding deity sits, but also, just as you enter, there is a pillar called the Dwaja Stambham. And you see it in the photo below. It is the first place of worship.

In most temples, there will be a series of steps leading up to the pillared porch behind the Dwaja Stambham. Here, in Airavateshwar, the steps are to the left and around the corner, so, the southern side of the main shrine.

The porches are called mandapams, and depending on the size and architecture of the temple, there can be a few of them.

This is where devotees traditionally gathered for meetings, or, if you are alone, this space provides a sedate ambulatory approach to the inner sanctum. A calming of your spirit before you view the deity.

The southern side of the temple and the steps leading into the mandapam. On the right, at the very edge of the picture is the Dwaja Stambham. Source

On festival days, temple deities were carried on wheeled chariots in a procession through towns and villages so that the populace could see and worship their gods. King Rajaraja Chola II constructed this part of his temple in the form of a chariot, rendering into granite the silhouettes of wheels, horses and elephants. The pillars holding up the mandapam and the ceiling also have exquisite carvings—stories of gods, kings and other mortals.

Enjoy the photo dump. The Airavateshwar Temple is every bit as beautiful as in these photos. More, if you are there, with the tranquility of the lush green lawns edging up to the outer walls of the temple complex, and the sunlit calm within.

All around the inside of the outer walls of the temple are a series of raised corridors, also originally to provide shade and a place of rest for pilgrims, and within which there are various other deities.

We walked around the temple courtyard in the pradakshina direction—clockwise; going the other way is inauspicious, and when we reached the northwest corner, I stopped a bit to tape the blog post video. And then, we made our slow way out.

An afternoon’s stillness:

There is a serene, sun-drenched tranquility at Airavateshwar, most unlike the bustle at that other famous Chola temple. The Tanjore temple, perhaps with a better publicist, and certainly with a major airport within city limits, is a more popular tourist destination.

It’s mammoth (maybe three times the size of Airavateshwar?) and its size is a marvel. (Again, future blog post.)

The front of the Tanjore temple, before the entrance gopurams, is clustered with vendors under crudely constructed shades selling plastic toys, whistles, animals and rattles in painted wood, slices of mango, pineapple and watermelon based on the season, and guides offering their services.

There are posses of beaming schoolchildren on a field trip, clad in their uniforms of blue and white, gaggles of college girls on the same purpose, and hordes streaming through the towering gopurams.

At Airavateshwar, it was us, and very few people—an undisturbed serenity lies over it all.

There was one old woman seated on the steps under the shade of the entrance gopuram, selling fruit and flowers in a blue plastic bowl for an archanai—a puja of thanksgiving and prayer—in the inner sanctum. One of the priests had leisure enough to come out into the mandapam and talk to us about the stories wrought so wonderfully in stone on the pillars and the base of the chariot.

And then, we wandered over the flagstones of the courtyard, warm under our feet, grass growing in between the seams. The only others were village women sitting in clusters, jute baskets by their sides, using bare hands to weed the clumps of grass.

Lunch was the next order of business and we found a nearby resort, with buildings—including the restaurant—scattered under a drowsy canopy of trees. A breeze wafted cool over us in that patchwork of tattered sunlight, dry leaves scurrying musically.

Food was good, but on that bright and heated day, the best part of the meal was an indulgence I don’t often allow myself. A tall glass of ice-cold rose milk.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next blog post—we come to America and a vital part of American history—The end of the American Civil War–Appomattox Court House–a village steeped in history–Part 1

Very well written.

Thank you, Ramkumar!

Thank you, most fascinating history!

Thank you!