(Part 1 of 5)

We’re on a long drive from…well, one place to another this past summer, and I’m bored and swiping on the map on my phone for somewhere to stop and stretch our legs. A name pops up. Appomattox. Appo-ma-ttox. Appo—

My kid, in the back seat (who’s obviously been paying attention in history class) pipes up, and fixes my memory into place.

We redirect the GPS, and we’re off. It’s a good thirty miles aslant of our intended route, but what matter, when there are such riches to be met at the end of it!

The village of Appomattox Court House:

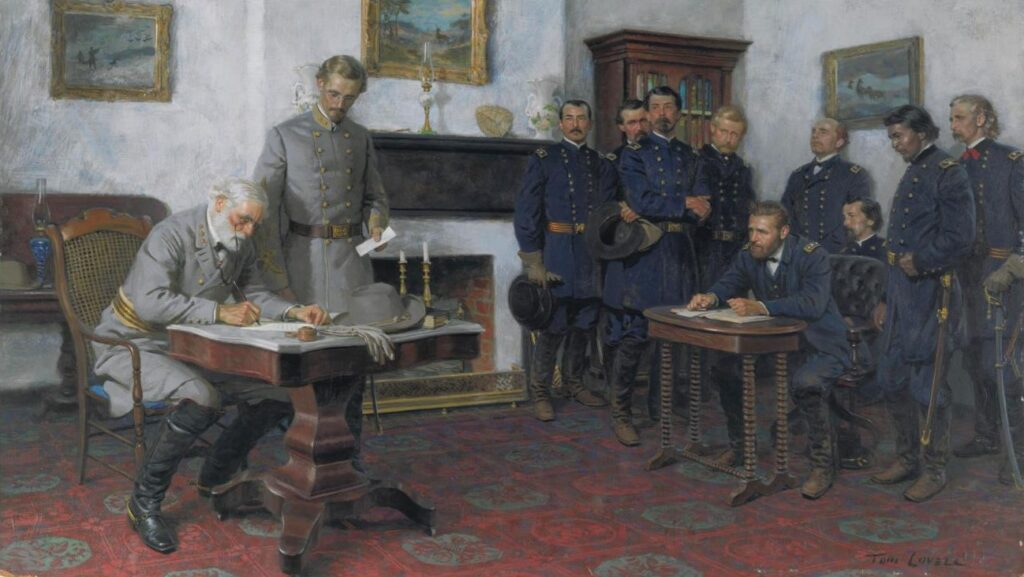

Appomattox Court House, a miniscule village in Virginia, thrust itself into prominence on the 9th of April, 1865, by hosting two most famous generals—Grant of the Union Army and Lee of the Confederate Army—as they signed the official document that brought an end to a crushing, expensive, and devastating civil war in the United States.

Grant and Lee met in the front parlor of Wilmer McLean’s home at Appomattox Court House. Lee brought along just one officer, Colonel Marshall (by his side in the gray Confederate uniform). Grant dismounted in the front yard and went in alone at first to greet Lee. Then, his officers came in—his staff and the generals who were nearby during this last campaign. Painting by Tom Lovell from here.

After the war, the village decayed, as the court house was moved to nearby Appomattox Station—three miles to the west. And, it wasn’t until 1940 that the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park was established in an effort to preserve this vital heart of American history.

There’s no telling what we’re going to encounter when we get there. Possibly, a modern recreation with realistic figurines of soldiers, a voiceover as we trundle along in a cart on a track, images projected on cavernous walls, and piped sounds of a battle. Or curators in Civil War costumes performing reenactments of that momentous day. (Full disclosure: I love a good reenactment, only just now, I’m in the mood for quiet.) Or newly-raised houses with shining siding and plaster. Or, all of the above.

When we pull into the parking lot—it’s none of these things. It’s a fine and warm day, with a swathe of golden light laid over the hills and the close cropped green of the turf, the trees in full leaf in the countryside. The houses in the village cluster below a slope of dark forest, looking blessedly normal, not pumped up out of proportion. It could well be the Appomattox that Grant and Lee saw—well, maybe a little cleaner, the grass grown in, not ravaged by battle and heavy artillery, but the same. Normal.

But what’s the name of the place?

Alexander Patteson (Patterson?) and his brother, Lilbourn, were the intrepid men who ran a stagecoach, beginning about 1809, between Richmond and Lynchburg—the latter is west of Appomattox Court House. And the road passed through the little village, which was then not much of anything at all.

This was very early, and there were no real roads to speak of for a very long time—just tracks in the ground, muddy, miry, with gravel pits, rocks and potholes aplenty. Which is where Patteson’s fortitude comes in. His passengers suffered jolts and bruises regularly, were thrown off their seats and bounced against the wooden ribs holding up the canvas cover of the roof, stuck in swamps…wheels broke, horses refused to budge, mules were as, well, stubborn as they are supposed to be—essentially, every trip was an adventure, with a threat to humans and property alike.

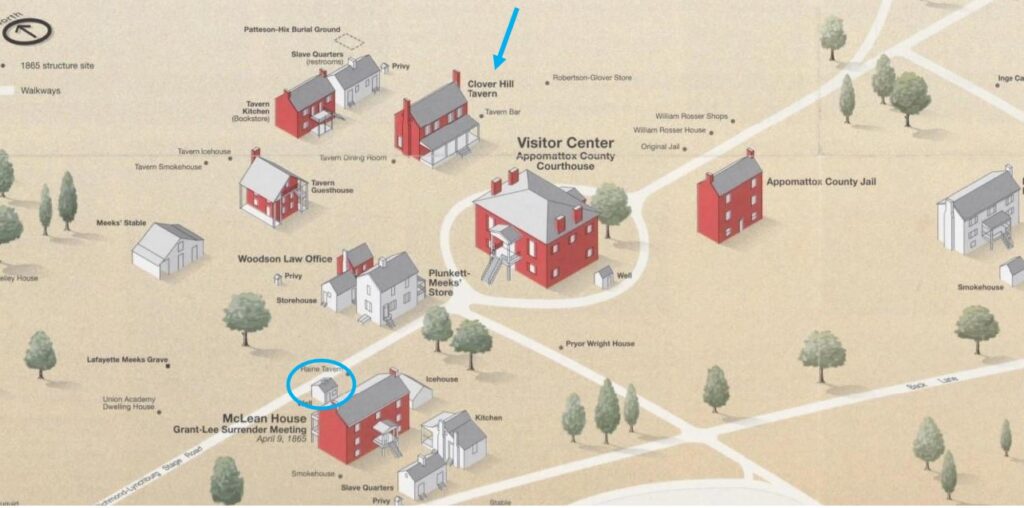

The first building in the Appomattox Court House/Clover Hill village area was this hotel—the Clover Hill Tavern. You see just the tavern in this picture, but it has (and had) various outbuildings—a separate kitchen, slave quarters, stables, smokehouse, icehouse, carriage house, and extra-guest quarters. It was also Alexander Patteson’s residence. All the tavern buildings you will see today are renovations of originals—so, original.

But, people needed to travel and the Pattesons bravely invested in the stagecoach route. The ‘coaches’ were anything but, merely wagons where travelers clambered into their hard, wooden seats from the front near the driver, and prayed that they would get safely to Lynchburg, a journey of some hundred-and-twenty miles.

In twenty years, it was a well-established route—the stage ran every day except for Sundays, drawn by four horses, and carried the mail and passengers.

Both people and horses needed some place to stop, sleep, and feed. So the Pattesons then established a tavern on the spot (of the current Appomattox Court House) along the route, and called it the Clover Hill Tavern. The tavern was built in 1819.

A new owner comes:

Alexander Patteson died in 1836 (thereabouts) and just before, he sold the tavern to a Captain John Raine, whose name is mentioned in the park brochure (much more on the Raines later).

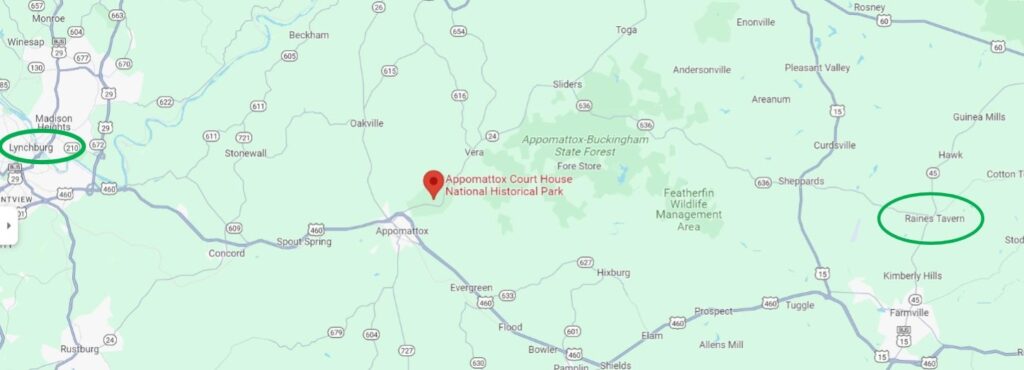

John Raine was no stranger to tavern-keeping, or at least, his family had done so for many years. Thirty miles east of Appomattox Court House, along that same wagon trail from Richmond, is another tiny hamlet, Raine’s Tavern. It was previously perhaps just known as the Raine Homestead, and, seeing the opportunity to make money from weary travelers on the Richmond-Lynchburg route that so conveniently passed their homestead, the Raines had established a tavern. Soon, I guess, the collection of houses that grew around the tavern formed itself into a village—called for the tavern.

Raines Tavern, the place, the village, is still on the contemporary map. Lynchburg, the end of the old stagecoach route is on the left; Appomattox Court House is in the middle. Image Source: Google Maps

At Appomattox Court House, John Raine and his wife ran the Clover Hill Tavern, and his brother Hugh owned 206 acres in the area. The population in the village of Clover Hill was now about a hundred-and-fifty inhabitants.

The locals, farmers and other workers, had to go to Farmville for their legal business—a trip of thirty miles. (Look just south of Raines Tavern on the map above for Farmville). On poor roads, this was time-consuming, costly, troublesome, and took their attention away from work at hand. They petitioned the Virginia Legislature to create a new county seat at Clover Hill—this meant creating a new county, and constructing a new court house because Virginia Code required it.

So, in 1845, the Legislature carved land from four surrounding counties—Buckingham, Campbell, Prince Edward and Charlotte. They named the new county Appomattox, after the river that ran just north and drained the land around. The new court house was to be established at Clover Hill village—again, according to code, every inhabitant in the county now had no more than a maximum of fourteen miles to travel for justice.

The new (1867) jail on the left; the court house on the right. This pathway was the stagecoach route; you see how the court house sits bang in the middle of it. The court house is exactly like its original, only it’s a reconstruction, built in 1964.

The first government building raised in the new village of Appomattox Court House was the county jail, just north of the stage road—it doesn’t exist anymore, the jail on the modern premises was built in 1867. The court house was built next, in the center of the village, forcing the stage road to curve around it in both directions before continuing toward Lynchburg.

John Raine moves his residence:

About a year after the incorporation of the county seat, John Raine sold the Clover Hill Tavern to Samuel McDearmon, who was the county’s delegate to the General Assembly and had already purchased much of Hugh Raine’s property in the village.

John Raine still owned land just south of the stage road, steps from the Court House, and here, he built another tavern, a single frame, possibly two-storey tavern and called it….Raine’s Tavern.

So, there were two Raine’s taverns—one at Appomattox Court House, and the other, owned by a brother, I think, thirty miles to the east on that stage route, which had lent its name to the hamlet also.

Both taverns had superb kitchens, and they were frequented not only by the stage travelers, but equally by the residents, who gorged themselves on roast pullets, venison, squirrels and hare, stoat (a young piglet), pound cakes, and sweet newly-drawn milk.

The blue arrow indicates the longtime location of the Clover Hill Tavern—it’s been here since 1819. The little blue circle, southwest of the tavern is around what is called the Raine Tavern—it no longer operated as a tavern in 1865 during the surrender at Appomattox Court House. And doesn’t exist today. Just behind the Raine Tavern is the new Raine Tavern (1848), better known now as the McLean House. Image Source

Wilmer McLean steps into history…a bit:

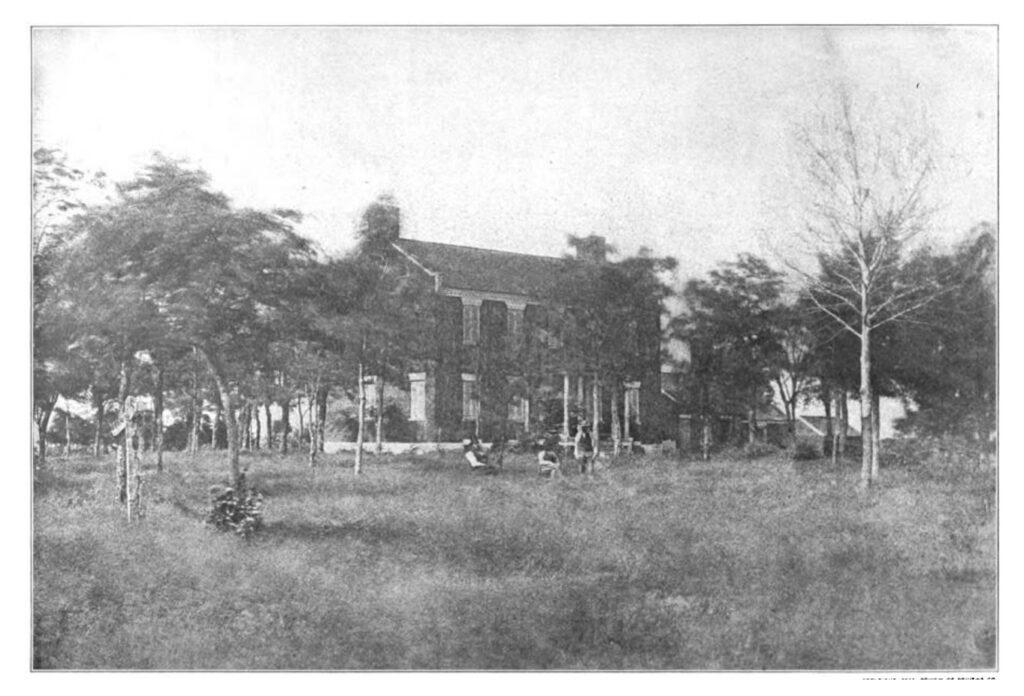

Trade must been good in 1846, because just two years later, John Raine built another structure to serve as the new Raine Tavern. This one was handsome, red brick and mortar, a wide porch running the length of the front, an upper balcony held up by white posts, and seven steps leading to the porch. It had three-storeys, the first two above ground, the third—the basement storey—more like a daylight basement.

The kitchen was in the backyard, along with the slave quarters, and the stables were accessed by a path on the left of the house which went past the structure to the back. Also in the back were the ice house, the smokehouse, and an outdoor privy.

This, became the new Raine Tavern, presumably with the same menu offerings as the other Raine Tavern which (still) stood in the front of this house.

The new Raine Tavern, built in 1848. It’s also the McLean House today (and during the surrender at Appomattox Court House in 1865)—not an original building but a reconstruction. Image Source

By 1863, two years after the Civil War had begun, the Raines were no longer substantial landowners in these parts, and Eliza Raine’s estate sold the tavern to a Wilmer Mclean, who had no idea—when he bought the house to convert it into his private residence—that he was stepping into history with that purchase.

What’s in the name?

So, to be clear now about the nomenclature. The village was first called Clover Hill, after the tavern established there. For a while after it became the county seat, it was still called Clover Hill, but when the court house was built, and the ‘trade’ in the area shifted to lawyering and court sessions, it soon became Appomattox Court House. And this, is how Grant and Lee knew it to be on that day in April, 1865, when the Civil War came to end here.

It is today called the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, and is preserved as such—no one lives there.

Just west of the park is the city of Appomattox, which was historically Appomattox Station, because it was a railway stop on the Southside Railroad from about the 1850s.

From this point, I’ll be referring to both places by their historical names: Appomattox Court House and Appomattox Station.

The American Civil War in numbers (my way):

A civil war is the most devasting conflict within a country, an internecine rivalry that pits friend against friend, each straining to recognize ideals and values that define the purpose, structure and rationale of a country. Think of it as a discord within a family, bound by ties of blood, faith and love, who cannot come to terms about their beliefs and tenets.

America was still a very young democracy when the Civil War began less than a hundred years after the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1776. It was a country in the midst of an expansion and settlement westward, with a stark contrast in the economics of the northern and southern states—the former were becoming increasingly industrialized, and the latter were supported by a vast network of slaves in their agriculture.

And, how did the westward expansion come into play? Because it became a question of whether these new states would be slave-holding or not.

So the Civil War delved into the very core of a nascent nation’s identity, as laid out in its constitution.

Just who, were we, the people? What did we stand for?

In November of 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, and that, effectively put an end to the question of slavery—he was a staunch abolitionist. First, South Carolina, and then six others states seceded from the Union—even before Lincoln was sworn in—and formed the Confederate States in an effort to protect their right to own slaves.

The war began on April 12th, 1861 with the first shot fired on the Union territory of Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Fort Sumter fell, and the north clamored for the taking of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

From Manassas to Appomattox:

Even though Fort Sumter was the first act of aggression by the Confederacy, the Civil War is most popularly bookended by the phrase, ‘From Manassas to Appomattox,’ because Fort Sumter was pretty much a rout; it fell in one day.

To take Richmond now, President Lincoln appointed Major McDowell as the commander of the Army of Northeastern Virgina—which would transition into the Army of the Potomac, which survived until the end of the war. McDowell had very little directive experience, but he did have some interest in Washington, and was promoted three ranks to brigadier-general to take command.

He set off with troops numbering 35,000 to meet General Beauregard of the Confederate Army in the First Battle of Bull Run—named after the river, and just north of the city of Manassas. Both armies had been rustled up equally quickly, with poorly-trained soldiers and a general lack of organization.

General Beauregard camped out in the farmhouse—well, it was a mansion, really—of Wilmer McLean, and some battles were fought in McLean’s fields.

Wilmer McLean’s Manassas home. It was a plantation of some 1200 acres and was called Yorkshire. Image Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, Editor-in-Chief, 1911.

Remember this name, because if there is one person in this Civil War who epitomizes the Manassas to Appomattox phrase, it is this man. The First Battle of Bull Run—the first real battle of the war, was fought on McLean’s lands. After the Second Battle of Bull Run, a year later, in 1862, McLean moved a hundred-and-fifty miles south in Viriginia, to a small—and what he doubtless thought—obscure village called Appomattox Court House where he hoped to escape from the ravages of war.

And, what happened? The Civil War followed him not just to his village, but right into his parlor—General Lee signed the articles of surrender in Wilmer McLean’s front room.

On April 14th, 1865, a mere five days after the surrender at Appomattox, President Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre by John Wilkes Booth, who sympathized with the Confederacy. The police forces took twelve days to hunt down and shoot the assassin. They did so on April 26th, 1865, on the day that General Johnston of the Army of Tennessee (Confederate) also held up the white flag and surrendered 90,000 troops—the largest surrender of the Civil War.

Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, was captured on May 10th, 1865.

President Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. Painting by Francis Bicknell Carpenter. Image Source

On the first of January, 1863, President Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all people held as slaves were free from that moment. As a consequence, as the federal troops advanced upon every place within the Confederacy during the Civil War, every person within was automatically granted freedom.

By the end of the Civil War, there were more than 1.5 million casualties—some 620,000 soldiers lost in direct conflict, and the rest—the majority—from disease, or casual wounds that would be minor today, or a lack of hygiene, or poor nutrition. The Confederacy suffered much heavier losses than the U.S. Army—almost until the end of the war, Federal officers were able to provide their men with rest and food, not so in the Confederacy.

The war had been fought to end slavery. Four millions slaves were freed by the end of the war.

And then, began the long reconstruction of the south.

And, the peace, healing and reconstruction started, effectively, in this quiet village of Appomattox.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Primary Sources: Campaigning with Grant by General Horace Porter, 1897; Lee at Appomattox by Charles Frances Adams, 1902; Various NPS brochures; The End of an Era by John S. Wise, 1901; Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, 1894; The Life of General Robert E. Lee by G. Mercer Adam, 1905; A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885; Ulysses S. Grant by Owen Lister, 1901; Memoirs of Robert E. Lee by A. L. Long, 1885; Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee by Rev. J. William Jones, 1906; Biography of Wilmer McLean by Frank P. Cauble, 1969.

On the next blog post—General Ulysses S. Grant: who he was, where he came from, and how he became commander-in-chief of the Federal army—the ‘how’ is pretty astonishing—The end of the American Civil War—Appomattox Court House—a village steeped in history—Part 2

BRILLIANT lesson in American History!

Thank you, Mathan Achayan!

Thank you, Indu, for a very well written short history of Appomattox. I would also like to suggest, Team of Rivals (about Lincoln and his cabinet), by Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Grant, by Ron Chernow. Fascinating history. My wife and I once drove the freeway through Pennsylvania, saw the sign “Gettysburg,” but did not detour and stop to visit the site. It is one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences we missed, and I look back on that decision with regret. You folks made a wise decision to stop.

Many thanks for the book recommendations! Yes, Appomattox Court House was a wonderful chance visit indeed. But, Gettysburg is still there 🙂 and I hope you get to visit in the future, Fred.