(Part 2 of 5); Part 1 here

The American Civil War ended in the village of Appomattox Court House, bringing to a culmination four long years of hardship, privation, and a vast destruction of life and property.

A civil war—and I’d made the comparison of it with a fierce family conflict—is fought between people who have. . .connections, either some point of contact somewhere in the past, or childhood tussles, or familial links, or even long adult friendships.

Most of the officers on both sides were West Point graduates, which meant four years of study, and four overlapping graduating classes, and so, they most of them knew each other from college. The ones who stayed on in the army after graduating had further associations, either serving below or above their antagonists in this American Civil War.

Interestingly enough, the two generals who commanded the opposing armies—despite their both being military men, both graduates of West Point, part of the army family—had come across each other only once. This was during the Mexican War (1846-48) when Lee was Chief of Staff for General Scott, who was directing the U.S. Army, and Grant a mere lieutenant. It was a. . .non-meeting, really.

On the 9th of April, 1865, when Grant and Lee assembled for the surrender at Appomattox Court House of the (Confederate) Army of Northern Virginia, Grant mentioned their previous encounter. Lee did not remember, or rather he was courteous enough to say that Grant must have been there, and honest enough to admit that he did not recall his face.

So, just who were these two men who brought about, and were present at this moment that began the healing of America after the Civil War?

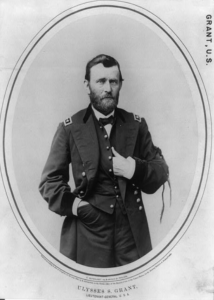

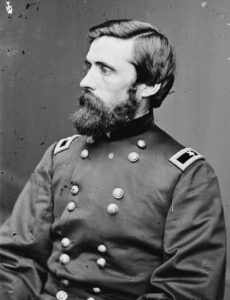

Grant, well before Appomattox Court House:

Ulysses S. Grant’s autobiography begins with this curious phrase, “My family is American—”

It was published in 1885, and he signed the preface on the first of July—twenty-two days before he died, seven years after his presidency, twenty years after he accepted Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

It was still a time of great immigration into the United States; there had been a sharp movement westward after the Louisiana Purchase, and the country was big, big enough to hold a giant influx of people fleeing their own lands. . .in search of that American dream. America was still being built by new Americans, who could yet cast longing glances backward at their erstwhile homes.

Not so, for Grant.

He, and all the American Grants, were descended from one man, a Mathew Grant, who came to America in 1630, to Dorchester, Massachusetts, from Dorchester, England. (The English Dorchester’s most famous resident is Thomas Hardy, the novelist. I wrote two blog posts on our visit to Hardy’s house there, Max Gate, Part 1 here, Part 2 here.)

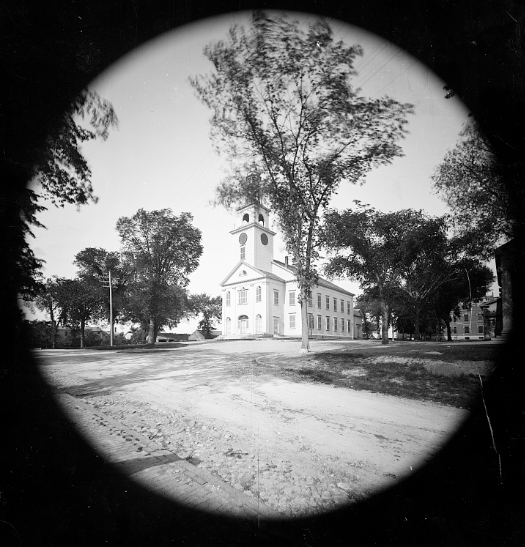

Mathew Grant came aboard the Mary and John, and was one of the original settlers in Dorchester. In a few years, he had become a freeman (just what it means; a term that granted the right to be free in colonial America) and a member of its First Parish Church.

The is the First Parish Church of Dorchester. This building dates to about 1897, I think, but is the fifth of this church’s reconstructed buildings. The first one, that Mathew Grant was a member of, would have been crude–logs and thatch.

Grant’s grandfather, Noah, had fought in the Revolutionary War (his great-grandfather had also been a soldier) and had eventually settled in Deerfield, Ohio, with a second wife.

Grant’s father, Jesse Grant, was the first child from this second marriage. When the second wife died, the family broke up—Grant’s grandfather went elsewhere with his two youngest children, and the others (including Jesse) were left to the care of families in the Deerfield area.

A first connection, John Brown and Ulysses Grant:

Eventually, Jesse Grant learned the tanning trade and went to work for Owen Brown in Hudson, Ohio, who owned several tanneries and was a very rich man. Owen Brown had fervent abolitionist ideas—he funded anti-slavery movements, and colleges which opened their doors to both women and African Americans.

It was here, under the tutelage of his first employer, that Jesse Grant received his own instruction in the abolition of slavery. He was a largely uneducated man, his formal schooling limited to ‘six months,’ and perhaps a few more months here and there.

But he was thoughtful, curious, eager to learn and he read all he could get his hands on. By the age of twenty, he was contributing articles to the newspapers and engaging in discussions with his townsfolk under the structure of debating societies.

Grant’s parents, Jesse and Hannah Grant in later life.

At the time of Jesse Grant’s employment—when he lived in Brown’s house, as was probably normal during that time—Brown’s son, John, was still a young boy, who had imbibed his father’s passion for the abolition movement.

As John Brown grew into manhood, Jesse Grant found him to be of ‘great purity of character, of high moral and physical courage, but a fanatic and extremist in whatever he advocated.’

John Brown attempted the raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859, hoping to capture the arsenal, arm slaves and incite them into rebellion. He was taken prisoner and executed. Lee had a hand in John Brown’s capture—another connection between people in this American Civil War—but more on that anon, in Part 3 when I speak of Lee’s background.

This raid on Harper’s Ferry was the first shot fired—so to speak—in the Civil War that ended at Appomattox Court House, that first nudge that began the momentum toward the war. A folk song arose around the circumstances, ‘John Brown’s Body,’ and it became the anthem of the Union soldiers.

Grant would have been aware of this connection with John Brown through his father, who had known him boy and man. But also, two days before the surrender at Appomattox Court House, when a contingent of his soldiers marched past him—exhausted, needing rest, but willing to shoulder their weapons and continue the fight upon his orders, they began singing ‘John Brown’s body.’

At that moment, Grant must have felt a tear in his eye—things had come a full circle. He did not know then that Lee would capitulate in two days, and Grant too was worn out by this long war, sick and plagued by headaches. If Lee did not surrender, he would have to chase him, more would die, perhaps even some of these young men raising their fresh voices in song, who had already sacrificed so much for their country.

If Grant’s grudging attention to his studies in his childhood is anything to go by. . .

. . .Appomattox Court House may never have happened.

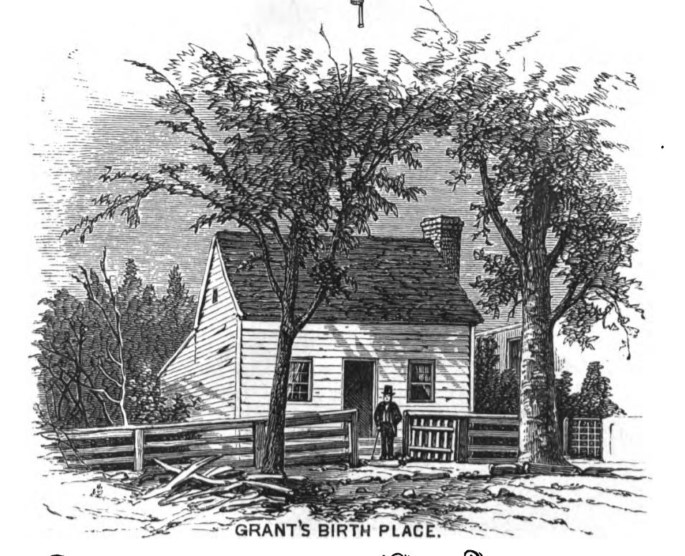

Ulysses S. Grant was his parents’ first child, the first son, and he was born in small single-frame cabin on the banks of the Ohio River at Point Pleasant that his father had built.

The tiny home in which Ulysses S. Grant was born in Point Pleasant–then and now. In the first picture, the gentleman in the front is supposed to be the physician who delivered him. Grant’s father planted those two trees. Image Sources: A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885 and Google Street View.

A year later, in 1823, the family moved some thirty miles east to the village of Georgetown, Ohio and Grant lived there until he went to West Point at seventeen.

Grant’s father was determined that his own children would not have the sort of lazy education that he had had, but in this early America, especially in a sparsely inhabited village in Ohio, the choices were few.

And Grant was not particularly good at his studies, nor was he interested in school work. It’s no wonder, because he describes the ‘subscription schools,’ (I guess that’s how they raised funds) with just one schoolmaster or mistress, who might themselves have been educated, but had little training to teach.

The schoolroom contained all the children whose parents had paid the subscription—from the very young learning their alphabet, to seventeen and eighteen-year-olds, presumably at a higher level of arithmetic, but still repeating ‘a noun is the name of a thing.’

For the rest, Grant does not complain of his childhood. His father owned a tannery—that was his trade, and also land which was put to corn and potatoes.

As the oldest son, Grant helped in all the chores. He ploughed the fields behind the two or three horses they owned, sowed the crop, harvested it and brought it in, looked after their cows, chopped wood for winter fires, and brought in the firewood. He also, desultorily, went to school each day.

Grant’s childhood home, built by his father, in Georgetown, Ohio—two views. The first picture is from the 1930s and shows the outer walls to be all white plaster. In the second, a current view, there’s brick over the main building and no front porch—possibly done by a later owner, because it wasn’t until the 1970s that the house was restored and preserved. Image Sources: First picture from here; second picture is a Google Street View.

His parents then gave him time off in the summer to go swimming in a nearby creek, or to take a horse and cart to visit his grandparents, or skate on the frozen pond in winter, or harness a horse to a sleigh over winter snows.

In 1838, Grant’s father applied to his Congressman (in whose keeping was the nomination—it still is) for the open seat at West Point, recently vacated by a neighbor’s son who could not pass the examinations.

Ulysses S. Grant comes (inadvertently) into being:

Grant had been christened Hiram Ulysses at birth. It was said that his grandfather liked the first name and his grandmother, the second. She had been reading François Fénelon’s The Adventures of Telemachus, the son of Ulysses, a book she had borrowed from her son-in-law, Jesse Grant.

The title page from François Fénelon, the Archbishop of Cambrai’s novel.

All very good, but at this point when Grant was admitted into West Point, his local congressman changed his name while sending in his nomination. The mistake was perhaps natural. Grant’s mother had been a Simpson, and the congressman thought that his full name was Ulysses Simpson Grant.

And so, Grant got his everlasting name—christened by someone who was neither father, mother, grandparent or relative.

The first step toward a military career:

In May of 1839, seventeen-year-old Grant set off on that long journey that would take him from his little village of Greenfield in Ohio, to West Point Academy in New York state. (General Robert E. Lee graduated from West Point ten years earlier, in 1829.)

He went alone. You would not send your kid to college now like that: what about the mattresses, the clothes, the laptops, the mini-fridges, microwaves and the teary goodbyes as you trudge back to your empty nesting lives, knowing full well you’ll be back on campus in a few weeks for the Parents’s Weekend, and will see your kid at Thanksgiving, for the Christmas break, and long weekends!

In those days, cadets did not leave their studies at West Point for the first two years, and although Grant’s father was in comfortable financial circumstances, he probably never thought of taking him to the school and settling him in.

The trip began at Ripley where Grant took a steamboat to Pittsburg up the Ohio River—three days. From there, he took a canal packet to Harrisburg, and from there his first train ride to Philadelphia. He dawdled in the city for a few days, spent a bit more time at New York City, and finally, some two weeks later, arrived at West Point.

West Point Military Academy, seen from the Hudson River. Image Source: Painting by Andrew Melrose from here.

At West Point, Grant was about as undistinguished a student as he had been during his school days. There was nothing to foretell his eventual success at Appomattox Court House. He was good at mathematics, but not much else interested him, and, looking ahead to a career, he thought he would return the Academy as a math professor.

As time passed, he learned all his drills, even saw General Scott (Lee was his Chief of Staff during the Mexican War), and felt a little thrill of admiration and inspiration—but not much it would seem; math was where he wanted to be.

He graduated and signed up for the 4th United States infantry. A cavalry regiment had been his first choice, but it was a crack regiment, not for the studiously indifferent, and he did not get in.

Mrs. Grant comes into being:

Grant’s first posting was at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Illinois. One of his West Point classmates, Frederick Dent, had his family’s slave plantation nearby, some eight miles north, and so Grant went to visit White Haven, as the house was called.

In time, the family’s oldest daughter, Julia, came home from school and visiting friends and Grant and she began courting.

Mildly, at first. Their encounters were mostly riding around the countryside, visiting friends and neighbors, typically properly chaperoned by one of Julia Dent’s younger siblings.

After many such meetings, Grant’s regiment was ordered to a new posting, and it was then he realized that Miss Dent meant more to him than he had previously thought. He asked his commanding officer for a few days leave before reporting for duty, and Lieutenant Ewell agreed.

Grant then set off to meet his lady love and convince her to be his wife.

Along the way, he had to cross a small stream with no bridge fording it, not a problem usually, because the stream either ran dry, or barely wet. On this day, in May of 1844, it was filled to brimming—the consequence of a few days of torrid rain.

He plunged in with his horse; they both went swimming downstream with the current, and after some struggle, he managed to make the opposite bank. But, he was drenched through, dripping with mud, his boots filled with water, his hat plastered against his head.

Julia Dent would probably reject him at first sight.

White Haven, the plantation Julia Dent’s father owned on Gravois Creek. Image Source.

When Grant arrived at White Haven, bedraggled and grubby, Frederick Dent kindly lent him a suit of dry clothes—but they were not the same size and the garments didn’t fit; most likely they hung loose on him, the coat sleeves draping over his hands and the pant hems dragging on the ground. Grant topped out at five feet eight inches; Frederick Dent was possibly much taller and bigger. (I actually searched around a bit for Frederick Dent’s statistics to be absolutely sure, but couldn’t find anything–only presidents and famous generals have their heights and weights measured for posterity!)

Whatever his appearance, or his stammering declaration of love, Julia Dent accepted him.

It reads like a rather cool business—Grant told her that had his regiment not been ordered away from Jefferson Barracks, he would not have come down on one knee before her. She, too, admitted the same, along the lines of hadn’t thought of ya until now (other than as my brother’s fellow officer). Or, something like that!

Grant’s obviously downplaying it–he’s writing a military memoir after all–because their affection was clearly strong.

The engagement thus begun lasted four years, during which time they saw each other only once, but they did write constantly, getting to know each other more—and better—before they married.

A second connection, Ewell and Grant:

Remember the lieutenant who gave Grant the extra days of leave to go a-courting?

When the Civil War started, Ewell was on the Confederate side, a general in the army. Grant fought him, and captured him on April 7th, 1865, two days before the surrender at Appomattox Court House. And Grant retained the same esteem and regard he had had for Ewell in the days of the ‘old army,’ for the man who was now his prisoner.

Oh, I don’t want this army life no more. . .yes, ma’am, I wanna go home:

Grant had early on written to a professor of mathematics at West Point, offering himself as an assistant whenever a position came open. He continued his studies independently while waiting for the appointment.

But it did not come soon enough, and Grant was still in the army when America annexed Texas (which had belonged to Mexico) and the Mexican War (1846-48) began.

Grant now made first contact with Lee briefly during the war, or saw him, or was at the same meeting—it’s not quite clear to me how exactly that happened.

He also came to know several other officers who went on to serve in either the Confederate or the national army during the Civil War. Later, as a matter of point, it was useful for him to have either served under their commands, or have known them in some manner that gave him an insight into their characters, whether they were in his own army, or opposing him.

After the Mexican War, he came back to marry Julia Dent on the 22nd of August, 1848.

Ulysses S. Grant’s wife, Julia Dent. Image Source

What did Jesse Grant think of this union for his son?

There’s no real record—Grant says very little in his memoir, other than it took him a year after he’d betrothed himself to Julia, to go back home and ask for formal permission.

Maybe that by itself is suspicious? Why a whole year? He could have written before; they must have known of his visits to Frederick Dent’s family house. But then, they would also have known that it was a slave plantation, and that Julia’s family owned slaves.

The third connection, Longstreet and Grant:

However it was, Grant married Julia, and then he went back into the army. His parents, supposedly, did not attend. His friend, Frederick Dent—Julia’s brother—would have been at the ceremony as a matter of course. There was another man, James Longstreet, who was certainly there, but there’s some doubt whether he was Grant’s best man or not.

Longstreet had graduated from West Point a year after Grant and Dent, and they both knew him, were friends and. . .during the Civil War, were on rival sides.

Longstreet, a general in the Confederate Army, fought the last battle of the war—the Battle of Appomattox Court House, before Lee’s surrender.

The Dent family house on 4th & Cerre streets in St. Louis where Grant and Julia were married on August 22nd 1848. Image Source.

After his marriage, Grant moved around in various postings, eventually to San Francisco and the Oregon Territory. Mrs. Grant returned to her home at White Haven and had her first child, a son they named Frederick Dent Grant—after her brother and Grant’s friend.

Across the country, Grant found the separations from his wife very difficult.

He could not bring her along with him to the wild, wild west. San Francisco, especially, was a city packed with gambling, eating and drinking houses. The California Gold Rush had begun and prospectors poured into the state, spending their money with abandon in the city. Men with gold in their pockets melted into the bay between the houses on the waterfront, and no one was wiser, or thought to ask where they had disappeared. There were no real laws, but those of thick skins and fighting fists.

Chaos was rife up north also, if of a different kind, in the Oregon Territory and the newly-formed Washington Territory. Everything was scarce, prices were blindingly exorbitant, and cooks commanded a salary that was greater than that of a captain’s.

In this time of peace (relatively!), an army officer’s pay hardly sufficed to support Grant and his family. But perhaps, he would not have given up such a definite source of income—however small—if there had not been another problem that had dogged him from his West Point days.

Grant could not hold his alcohol. His fellow cadets at the Academy had once made him promise to keep from drinking when he had gone home on his first furlough; at the school, he had been reprimanded by his commandant—if he did not change his behavior, he could well be dismissed. So, Grant had remained as sober as he could most of the days.

That changed when he was on the Pacific coast—the days were long, there was not much to do, not much threat to his forces, he missed his wife and children. . .and so he began drinking again.

It became so untenable that his commanding officer demanded his resignation from the army. He would hold it for a few months, not send it to Washington yet, and Grant was to be given a chance to clean himself up.

Grant didn’t. He could not at that time, and so, in 1854, Grant left the army, making his resignation official.

How then did this man end the Civil War at Appomattox Court House? Read on. . .

A soldier no more:

When Grant came back home, they had two children—boys, the younger of whom he had not yet seen. His father-in-law had seemed rich, with his plantation and his slaves, but things had not been going well for a long time–even before Grant married Julia–as a long-standing lawsuit had slowly depleted his income.

Still, there was something.

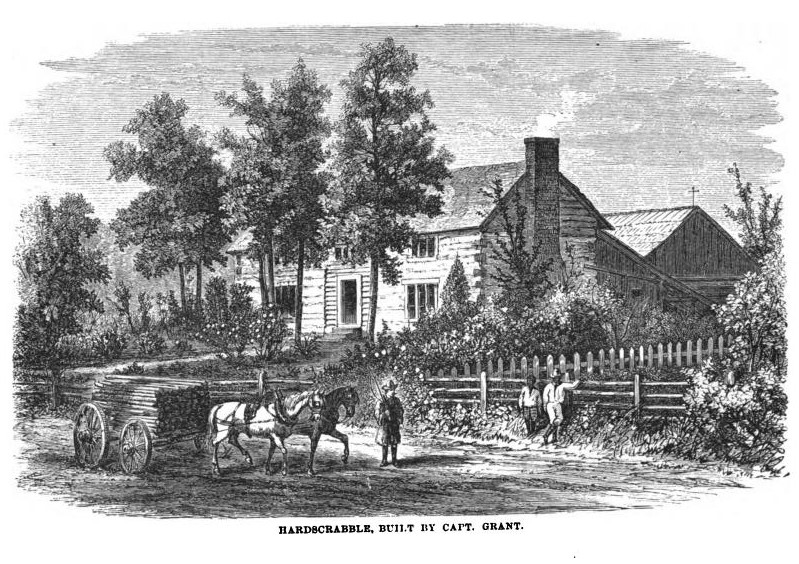

His wife owned some land close to the plantation, and they moved there to clear the trees and the brush and to build a new house. It was a back-breaking life.

Hardscrabble, the house Grant built near White Haven. Image Source: A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885.

Grant cut trees down himself, hewed them, shaped them into logs and built a cabin in the woods. Trees were aplenty, and he took logs in a cart to the market. He worked the farm, grew potatoes and wheat, bought some livestock, and hearkened back to his childhood days when he had labored on his father’s lands.

The Grants did not stay long in the cabin; they moved back to White Haven and here Grant looked after the family land—he did not own the slaves, but he oversaw them. His wife, however, owned slaves, given to her by her father.

By most accounts, Grant was uneasy about employing slaves as forced and unpaid labor. When one of his brothers-in-law proposed to travel to the Pacific coast overland to set up a business there, a family slave named George wanted to go with him. Grant gave permission. George protected his young master on that perilous journey, and then married and lived in California, a free man.

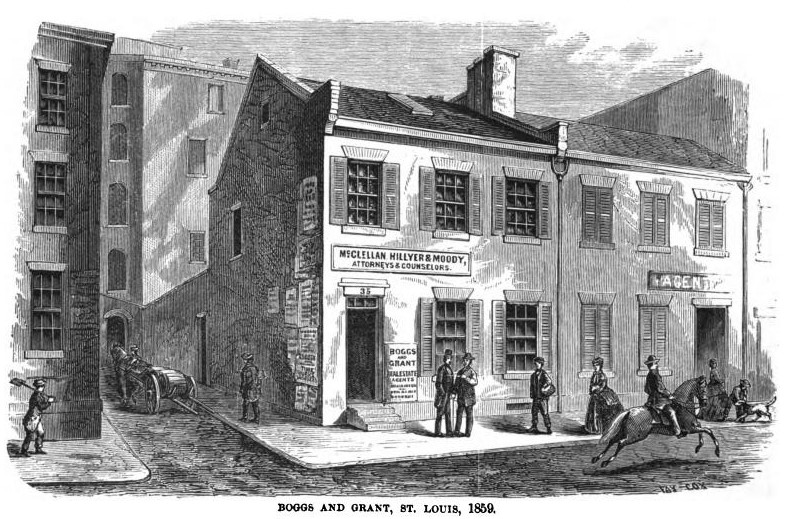

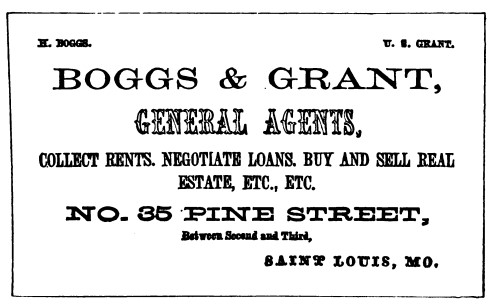

But the White Haven plantation had been steadily in decline, the money was still not enough, and so Grant joined a Dent relative, Harry Boggs, in a real estate agency in St. Louis. That failed.

Grant sets up shop with Harry Boggs. Image Sources: A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885.

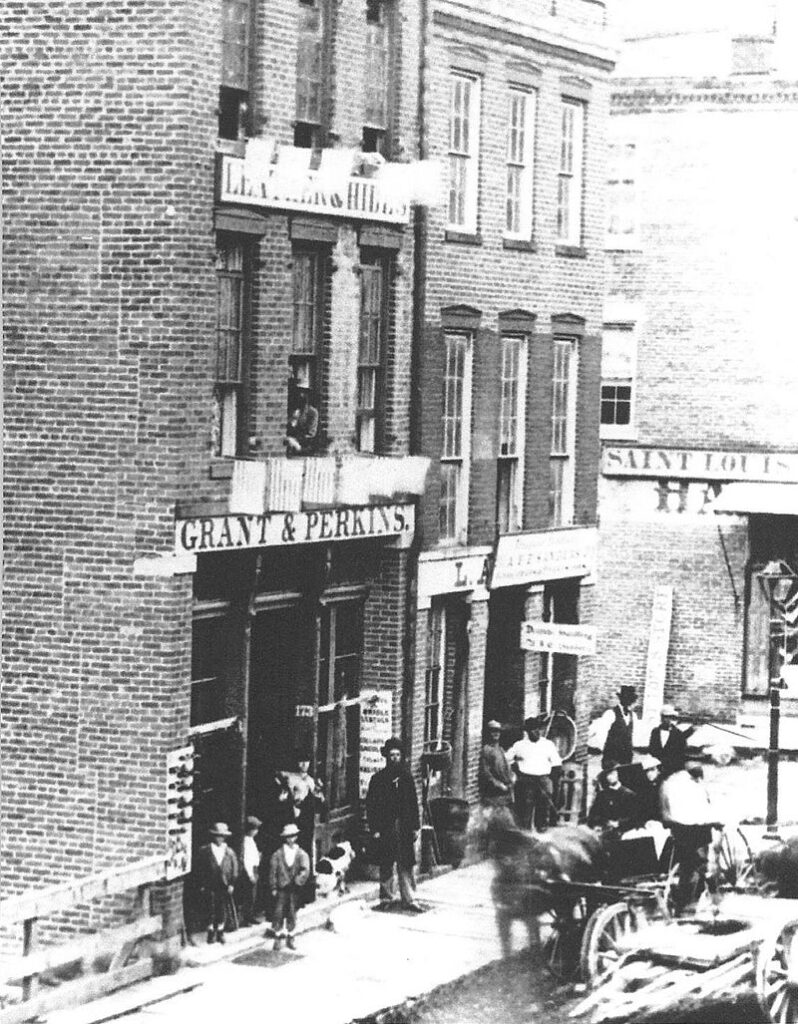

He tried his hand at yet other things, but they were none of them a success. So, he turned finally to his father who had moved and set up a leather and tanning store in Galena, Illinois.

Grant goes home. . .so reluctantly:

It’s curious that Grant hadn’t thought of approaching his father earlier, especially given that Jesse Grant was extremely prosperous at this time. But perhaps that rift caused by Grant’s marriage into a slave-holding family was. . .unbreachable.

Grant and his wife had visited his father’s house—so they were on companiable terms, certainly—but maybe Grant had some pride, and his father could not meet him halfway as long as he continued a strong association with the Dent plantation.

But now, with no discernable source of income, he went to his father in Galena, Illinois. Could he be given a position in the family leather store? Grant’s younger brothers were primarily in charge of the business and they agreed to take him on at six hundred dollars a year.

The aggravations of this new life must have been enormous.

Grant had never taken to his father’s ‘trade,’ tanning, even in his childhood, preferring to work on the land instead. And, he had to work under the supervision of brothers much younger than him. He did not know the stock as well as his brothers, and he was constantly being superseded by them when customers came in asking for one specific thing or the other.

He kept his equanimity however—he had a wife, and by now, four children to feed, house and shelter.

When Grant joined his father and brothers in Galena in 1860, he had been out of the army for six years, although he had kept up friendships with his fellow officers.

The Civil War started a year-and-a-half later. Four years from then, he was accepting Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Private citizen Grant leads a successful army to end the Civil War?

Think about this for a moment.

Grant was no lifelong soldier—his hiatus from the army had stretched seven-and-a-half long years at the moment when the Civil War began.

By his own account, he had been an unexceptional student at West Point, joining the Academy only because his father told him to; he guaranteed that mediocrity by graduating twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine. (Lee graduated second in his class–if you go just by that, would you think that Grant would force Lee to surrender at Appomattox Court House?)

He had not left the army—he had, in effect, been kicked out because he could not control his drinking. He seems to have been sober after, anyhow, if you consider the grueling work he assumed as a laborer, a farmer, a hauler of logs from Hardscrabble to the St. Louis market. He also knew that he could not take even one drink—the was no social drinking for him; it was all or nothing. And, he chose the nothing.

But, however abstemious, he had drifted into other jobs he was equally apathetic to—the real estate agency, a place at the St. Louis customs house, a clerkship—and had been successful at none.

So, how did Ulysses S. Grant become one of the most able generals of a U.S. army?

Future presidents must be super-keen on politics, surely?

The first election Grant voted in—at the age of thirty-four—was the presidential election of 1856, and he cast a vote for the Democrat Buchanan, or rather, against the Republican candidate.

This Democratic party was pro-slavery and Grant leaned Democratic, even while the whole question of slavery gave him some unease. But, he explains in his autobiography, that if a Republican (anti-slavery) candidate had won, the country would have immediately seen the secession of the Democrat-led slave states, and have been plunged into a war.

And that, in essence, is what happened after Abraham Lincoln won the November 1860 election.

There were three other candidates on the ticket—two were Democratic and Southern Democratic nominees, the third was from the Constitutional Union Party, which sat on the fence and tried not to consider the question of slavery at all.

Grant’s father and his brothers, with whom he was now living and working, were staunch Republicans. He was not himself eligible to vote in the 1860 election, since he had not been long enough in Galena to establish residency.

He refused to join any of the torchlight marches through Galena, for either party, but did stop him from drilling the members of the Republican party. He’d gone to listen the Democratic candidate, and had come back thoughtful. His politics were changing.

Grant & Perkins was the leather store Grant’s father ran with a partner—he bought him out in a while. The store, when Grant worked here, was run by his brothers, Simpson and Orvil. Image Source.

On the night of the election, the Grant store was kept open beyond closing hours, and a party went on through the dark. Grant celebrated with his father and brothers, and took around trays of oysters and alcohol, but did not touch any of the drink himself.

The fourth connection, Rawlins and Grant:

A few days after the first shot of the Civil War was fired by the Confederate Army on Fort Sumter, a Union territory in South Carolina, President Lincoln called for volunteers for the inevitable war.

In Galena, the men convened in a first public meeting, and Grant was asked to preside because he had been in the army.

There, he met John A. Rawlins, a sometime-farmer, a once-charcoal-hauler, a now-practicing-lawyer, who had taught himself the law. And, a fervent Democrat, who had stumped for the Democratic candidate who Grant had gone to hear.

John A. Rawlins during the Civil War, wearing his uniform of Brigadier-General. Image Source.

Like Grant, Rawlins’s politics had made a deep change. Firing upon Fort Sumter was a shot in the heart of the United States, a flouncing of its laws, a traitor’s bullet upon the flag. Patriotism, he said, knew no party affiliation, it was to the country.

“I have been a democrat all my life; but this is no longer a question of politics…We will stand by the flag of our country. . .”

John A. Rawlins, April, 1861, Galena, Illinois.

When Grant was asked to lead a brigade, he enlisted Rawlins on his staff—by the end of the Civil War, General Rawlins was his Chief of Staff.

This army life. . .it’s for me, after all?

For a while, Grant dithered around. He was not offered a commission in the army, he asked for it, but it was ignored. Eventually, he was appointed to the colonelcy of the Twenty-first Illinois Volunteers—a regiment he had mustered earlier.

When he first visited them to do a review, they were in disarray, had rebelled against their previous commander, had no discipline, and mocked Grant’s misshapen hat and his old coat, bare at the elbows. Grant’s West Point training kicked in, and he brought them to heel in short order.

After two months with this regiment, Grant was promoted to brigadier-general. His first command was at Cairo, Illinois, and included parts of southern Illinois, western Kentucky and Tennessee.

For a while, he chafed under the necessity to get permission to attack the Confederate forces, and once, he set out and captured Paducah, Kentucky, without orders. Then, over the next year, came the battles of Belmont and his assaults on Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. In the latter most, he captured 12,000 troops.

President Lincoln, who was most certainly paying attention to war news, nominated him for major-general of volunteers, and the Senate confirmed the nomination.

Whatever Grant had been in his earlier avatar as a soldier, he had blossomed into a commander who was steady, reliable, considerate of his men, aggressive, and determined to succeed.

The Ulysses S. Grant of the Civil War had come into being. Primed and ready for Appomattox Court House.

The fifth connection, Sherman and Grant:

It was at this capture of the forts at Donelson and Henry that Grant met William Tecumseh Sherman, who would become the general who ended the Civil War officially, when—after Lee’s surrender—the Confederate general Johnston gave up 90,000 troops to him.

General William T. Sherman near the Union lines at Atlanta. Image Source

Sherman had been superintendent at the Military Academy of Louisiana, and when the state was considering secession, he gave up his post and retired into civilian life.

When the war began, he signed up with the U.S. Army, and fought in the First Battle of Bull Run (that which was fought on Wilmer McLean’s lands—Wilmer, if you’ve read Part 1 of this blog post, was the man who had the happy advantage of the Civil War beginning and ending around him. He fled to Appomattox after the Second Battle of Bull Run, only to have Grant and Lee follow him, into his very front parlor, to come to terms about the surrender. More on Mclean, when we get there—Part 5 of this blog post.)

Anyhow, back to Sherman, who’s now in the U.S. Army, and who has, most fortunately for him, met Grant, the man who will give him his future commands.

Lee had a connection with George Washington, but Grant also?

Over the next two years, Grant proved his worth over and over again in various campaigns, and in 1863, Lincoln made him a major-general in the regular army—Grant had come home again.

The next year, the president promoted Grant again. He was to lead the entire U.S. Army. His congressman from Galena, Elihu Washburne, proposed a bill (re)creating the post of lieutenant-general, and it passed both houses.

On March 1st, President Lincoln nominated Grant for the post, and the Senate passed the nomination on the 2nd.

This rank of lieutenant-general had previously only belonged to one man, George Washington, and had never been used since.

Grant had to go to the capital to accept his commission personally from the president. He went, stayed at Willard’s Hotel, was mobbed everywhere—the newspapers had been full of his victories for a few years now—and attended a reception on March 8th, 1864, where he met his president for the first time.

Grant then set about assembling his staff, making Rawlins (the Galena lawyer he met at the first public event after Fort Sumter) Chief of Staff, his brother-in-law, Frederick Dent, an aide-de-camp, and appointing Colonel Ely S. Parker, who was Native American, as an assistant adjutant-general.

Remember Parker’s name, in Part 4 of this blog post, he will play a significant role at the surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Then, Grant went to war.

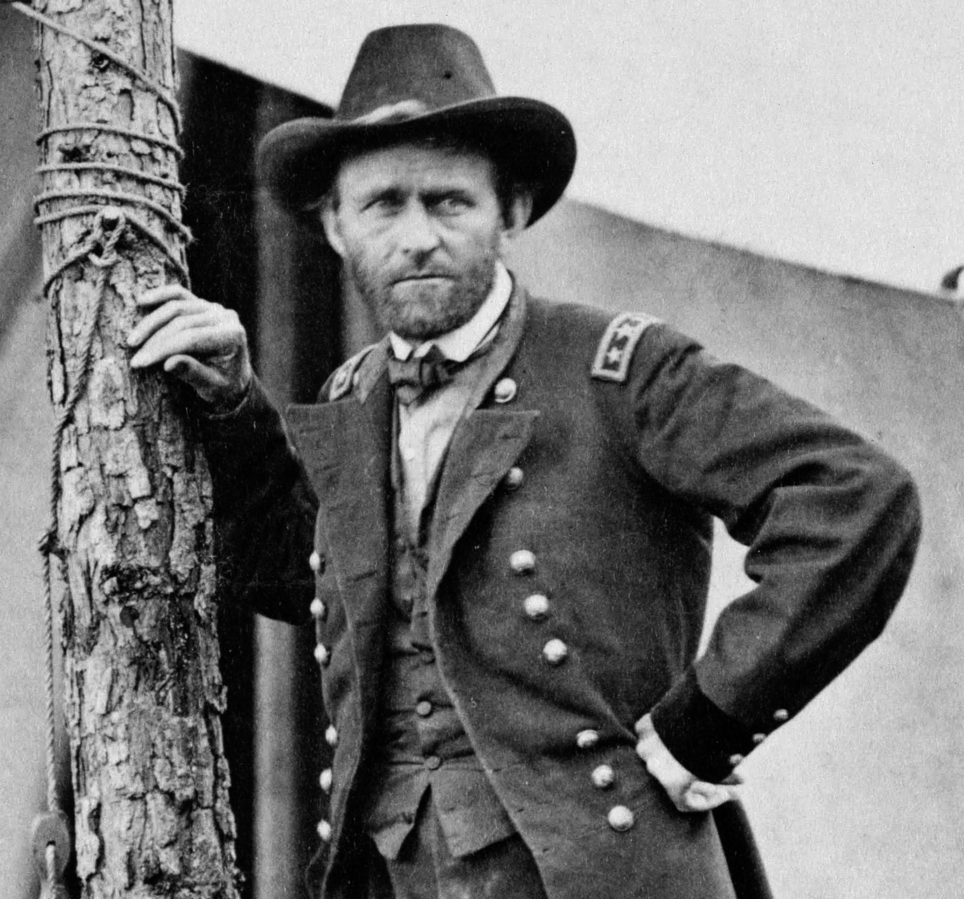

The Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Army at Cold Harbor. Image Source

In April of 1861, he had still been a clerk at his father’s leather shop. He had, as part of his duties–when he sold a hide of leather to cover a desk–carried that hide on his shoulder, draped it over the customer’s desk, and nailed it in place.

Then, he had begun soldiering again.

In a scant three years, he was lieutenant-general of all Union Armies.

Thirteen months later, he ended the Civil War at Appomattox Court House. Grant was forty-two years old that day.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this blog post, please consider sharing it, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next blog post—General Robert E. Lee’s personal history, and how he came to take part in this essential part of American history—The end of the American Civil War—Appomattox Court House—a village steeped in history—Part 3

Primary Sources: Campaigning with Grant by General Horace Porter, 1897; Lee at Appomattox by Charles Frances Adams, 1902; Various NPS brochures; The End of an Era by John S. Wise, 1901; Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, 1894; The Life of General Robert E. Lee by G. Mercer Adam, 1905; A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885; Ulysses S. Grant by Owen Lister, 1901; Memoirs of Robert E. Lee by A. L. Long, 1885; Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee by Rev. J. William Jones, 1906; Biography of Wilmer McLean by Frank P. Cauble, 1969.

Dear Indu,

I finished reading your Blog (Part 2) just now. It is obvious that you had mastered all the pertinent historical facts which is quite admirable. You have succeeded in transforming ‘prosaic’ history into something like a story — interesting and enjoyable. The sub-headings make the narrative meaningful and easy to grasp. Through your masterful presentation of Gant’s story you have made me a keen student of American Charitra! Grant’s story holds a moral lesson apart from his military victories. That is, one should not lose heart when unanticipated set backs happen. Keep up the good work, Indu.

With all good wishes and regards,

Mathan Achayan

Thank you, Mathan Achayan! I love the ‘American Charitra!’ So glad to hear you’ve enjoyed reading this.