(Part 1 here)

The New Cathedral Rises

The first service at Salisbury Cathedral was held in 1225 CE, when Bishop Richard Poore deemed that enough of the church had been completed. The next year, in March, the Earl of Sarum, William Longspee, who had been present at the dedication of the foundation (he laid the fourth stone)—died. He is the first person to be buried in the cathedral.

The effigy of William Longspee, Earl of Sarum, at Salisbury Cathedral. Source.

Longspee was the illegitimate half-brother of two kings, Richard I and John. It was John who signed the Magna Carta on June 15th 1215, at Longspee’s urging, bringing some measure of peace between a disliked king and rebel barons. There were thirteen original copies of the Magna Carta, one of which—presumably because Longspee had been witness to the document—made its way first to the cathedral at Old Sarum, and then here, to Salisbury when the old cathedral was translated to this spot. It’s still at Salisbury Cathedral, displayed in the Chapter House.

The West Front of Salisbury Cathedral.

And…the work goes on…and on: Bishop Richard Poore was transferred to Durham in 1228, and left strict injunctions to his successor, Robert Bingham, to finish the work on the building. But, Bingham was a fairly lazy chap, spendy too, it would seem. When he died in 1246, the church building fund (or something like that) owed one thousand seven hundred marks to the treasury, and, the church was not finished.

William of York became bishop next, and died ten years later, with the cathedral still not completed. Two years after that, Bishop Giles de Bridgeport finally called the building done. This was the 30th of September, 1258—thirty-eight years after work had first commenced.

By this time, according to contemporary accounts, the bishop’s palace and the surrounding buildings were also finished, but not the chapter house and the cloister. All built, in the city which was called now, New Saresbury.

What’s in a name? There’s a fair bit of confusion about the name. Was it Sarum—New Sarum—Salisbury—or, as here, Saresbury? Most sources agree that the old town was called Salisbury or Sarisburie, and sometime in the 13th Century, a corrupt reading of documents led to the name Sarum. Today, the cathedral stands in Salisbury (two miles southeast of the old town) and its original space and the fortified town, now in glorious ruin, is called, helpfully, Old Sarum.

The vaulted ceiling of the Nave with the pulpit in the foreground.

Even with the dragging out of the construction (well beyond what was an initial seven year estimate?), Salisbury Cathedral has a more or less uniform, and Gothic, style of architecture, because the style did not change much in those thirty-eight years. When it was completed in 1258 A.D., the final cost was about £26,000 or 40,000 marks.

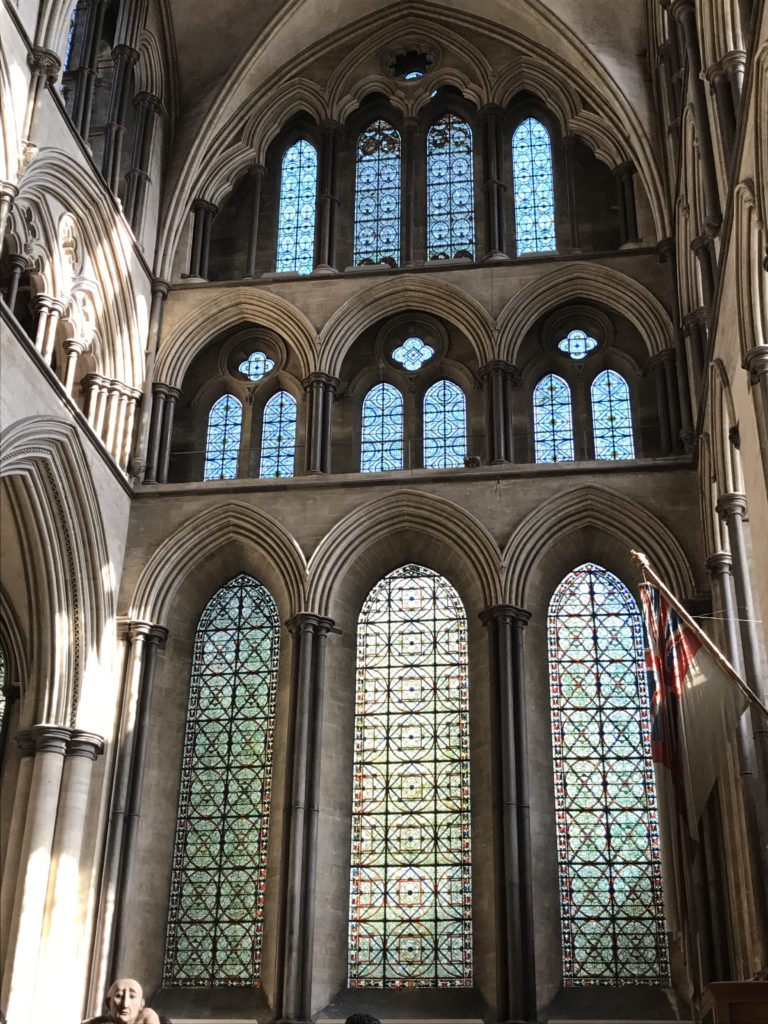

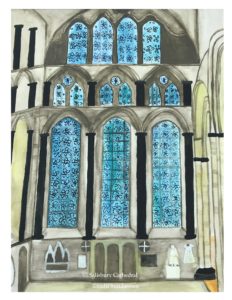

The stunning stained glass windows of the South Transept.

The stunning stained glass windows of the South Transept.

The stones for the spire: There’s no exact date or confirmation of when the spire, the tallest in England, was built, but most probably between 1329 and 1375 CE, when Robert de Wyvil was bishop. He was a coarse and ugly man, uneducated, raised to his position by virtue of being from a family that had influence. It was said then, that if the pope had seen him, he would not have elevated him to this lofty bishopric. But, neither his looks nor his lack of learning stopped him from holding the office for forty-five years.

The spire at Salisbury Cathedral.

He was also a combative man, contending that the church and the fortress of Old Sarum (there’s some dispute whether it was Old Sarum or the castle at Sherborne) belonged to the church at Salisbury. William de Montacute, then Earl of Salisbury, who owned the fortress at old Sarum contested this.

Initially, it was all done in a civilized manner; Bishop Wyvil sued, the Earl responded in the courts, and then the court said o.k., duke it out, here’s a time and here’s a place, and whoever lives at the end of the combat wins Old Sarum!

Now, of course, neither the Earl nor the bishop was going to show up for the meeting of twelve paces at dawn (so to speak) themselves—they sent representatives to fight to death. As, um, interesting as this manner of dispensing justice sounds to us today, it must have been fairly common then, and the bishop’s man and the Earl’s man suited up in armor emblazoned with the arms of their patrons and assembled to fight. At the very last minute, the king sent an order by a messenger, stopping the combat. Very exciting stuff!

They afterwards came to a compromise and the Earl gave up Old Sarum to the bishop in exchange for two thousand five hundred marks. Wyvil promptly then had the king sign an order in which he was granted the stone walls of the Old Sarum church to be used for improvement of the new church at Salisbury.

Bishop Wyvil later acquired the castle of Sherborne—he died there and is buried there—hence, I think, the misunderstanding about whether it was Old Sarum or Sherborne he wanted in the beginning. Either way, he got both, and Salisbury Church got its spire. From my reading of this, I’m assuming that the stones of the old church at Old Sarum were used to build the spire, also because nothing remains of the old cathedral at Old Sarum—nary a wall—just the footprint of the foundations.

The fortress at Old Sarum today, with the footprint of the old cathedral, below left, and the keep, center. Source.

The riches of Salisbury Cathedral: Over the years of its existence, with the help of ambitious bishops, the cathedral at Salisbury accumulated a fair bit of tangible wealth.

Around 1534 CE, King Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and persuaded all English churches to convert to Protestantism. His commissioners then roved the countryside, demolishing churches and monasteries that wouldn’t listen to the king’s ‘coaxing,’ and enforcing that persuasion in churches that did agree. Thankfully, Salisbury Cathedral made that switch over, and in the process, the commissioners made an inventory of the church’s belongings—which came to seventeen pages full of stuff.

The North Aisle.

There were paintings of Christ and the Virgin Mary, framed in silver set with precious stones and pearls. Pyxides (cylindrical boxes) of ivory, crystal and silver, one which contained the chain with which St. Catherine tied up the devil. Several silver chests, inside one of which were “the relics of eleven thousand virgins.” (I’d be curious to know what exactly those ‘relics’ were—not their remains, surely? Difficult to see how you can cram eleven thousand virgins into a single chest!) Several gold and silver crosses, some enormous. Many gold candlesticks, studded with precious stones and jewels. Crystal and silver ampoules, one of which contained the tooth of St. Anne, and another with the toe of Mary Magdalene. Censers of gold ornamented with leopard heads, chains and rings. Yards and yards of white satin, red and white velvet and gold cloth. Basins of gold and silver for holding holy water.

You may not be able to see these riches when you visit Salisbury Cathedral, but what you can see is equally priceless. In the Chapter House is an original copy, dated 1215 CE, of the Magna Carta, given to the church at Old Sarum and moved to the new Salisbury church. And also, the oldest working clock in the world, which dates to about 1386 CE and is displayed within the church.

The South Transept.

We visited on a warm, warm day, as the sun slanted in between the trees, and positioned cool shadows on the massive greens around. It’s called a ‘close,’ all that green space of neatly trimmed grass surrounding the cathedral, and it’s the largest close in England, clocking in at 80 acres. Here, finally, was the space for the houses for the bishop and the clergy of the church surrounding the close, and none of the restrictions of the cathedral at Old Sarum. And here, Salisbury Cathedral has dwelt for the past 800 odd years.

They were setting up for a military event the next day, and several officers in uniform walked around in the close with the clergy. A lady in the soccer field beyond the cathedral said that Prince Charles was to be the chief guest. “It’s a see-cret,” she said, closing one hazel eye in a wink. And then, with a rich laugh, “But, we all know.”

I grinned, liking the way she tells this little non-story. Unfortunately, we cannot come back here tomorrow to gawk at the prince—we have to visit that third member of the ley line. Stonehenge.

The choir stalls.

We went for evensong—the evening service with, as the name suggests, the choir. They seated us in the Quire, on ancient wooden benches carved by hands long gone, and the voices of the choir rose around us and diffused through to the gorgeous vaulted ceiling. The priest read a passage from the Bible, the choir sang again, and the sun flowed through the windows and laid patterns on the ground. When we left, the stones still hummed with music.

Outside, people stretched out on the lawns, some in the sun, some in the shade, and chatted desultorily. We sat also, and watched the sun warm the age-old puce-colored stone and the carvings of the west front of the cathedral, looked up at that tall spire etched against that blue, cloudless sky. And then, it was time to leave, and walk down the west cloister walls, looming to our left, barrack-like, until we reached the car park.

The North Transept at Salisbury Cathedral.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—Max Gate: The house that Tom built—Part 1—Thomas Hardy’s home in Dorchester

One Reply to “A Church in translation–Salisbury Cathedral—Part 2”