The old Cathedral at Sarum; the new one at Salisbury

Old Sarum; the Salisbury Cathedral that was: When the bishop conducted services at the cathedral at Old Sarum during a storm, gales raged high and howled strong, snuffing out his voice. The sparse congregation, huddling together, strained forward to listen as the wind grabbed the words from his mouth and flung them into the uninhabited corners of the building. Rain streamed through the leaky roof, drip-drip-dripping with a clatter onto metal plates strewn around the church to catch the water. It was cold, it was damp, and the fireplaces threw out a miserly, grudging heat.

With all that rain, there was still no real potable water in the fort at Old Sarum. The wells ran deep, but hauling up this sweet water in sufficient quantities for the entire fort was a chore. And pricey.

Water, water, everywhere, but not a drop to drink.

Old Sarum, with the footprint of the old cathedral, below left; the keep, center, and the encircling fort walls. Source.

Old Sarum, with the footprint of the old cathedral, below left; the keep, center, and the encircling fort walls. Source.

English churches pride themselves on being available to worshippers all through the day, and especially for services on holy days—Ash Wednesday, during the celebration of orders, at Christmas. But, only the brave ventured to the cathedral, because they first had to pass the gates into the walled fortress of Old Sarum under the watchful and suspicious eye of the Castellan. Old Sarum was a military fortification and the soldiers were not particularly religious or devout. And, they didn’t care if you came to the fort to worship at the cathedral—if they felt like it, you still got knocked about.

The soldiers also harassed the clerics, not allowing them to stray outside certain paths during their processions, and even beating them up, by one account. Sarum provided no housing for the clergy—usually a staple of the church—and they had to instead rent from the laity.

It was, taken together, an untenable, unhappy situation.

Old Sarum Cathedral, the footprint.

Old Sarum Cathedral, the footprint.

The Pope intervenes: Bishop Richard Poore, sometime in 1217 A.D., sent messengers to Rome, asking permission to move, ‘translate,’ the church from within Old Sarum to another, more accessible and wholesome site.

How do I know all this, from a distance of almost 800 years? Because, Pope Honorius III, in granting the request in the form of a papal bull, gave not only his permission for the move of the cathedral, but also helpfully detailed every grievance.

Honorius didn’t write his bull willy-nilly; he had his Papal Legate, Gualo, Cardinal of St. Martin, investigate the truth of the matter beforehand. Gualo presumably traveled to Old Sarum cathedral, sat shivering through at least a service or two, encountered the rude stares of the soldiers in the town, and saw for himself the troubles Bishop Richard Poore spoke of. Gualo recommended the moving of the church, and Honorius agreed.

Bishop Poore on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral (holding in his right hand, it would seem, a model of the cathedral). Source.

Bishop Poore on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral (holding in his right hand, it would seem, a model of the cathedral). Source.

The Cathedral site: And so Salisbury Cathedral came into being. Legend has it that Bishop Richard Poore shot an arrow in the direction where he wanted the new cathedral to be constructed, and it killed a deer on that spot.

If Poore did this from Old Sarum, he had a mighty strong, and soldierly, arm—Salisbury, the site of the (new) cathedral, is two whole miles southeast of Sarum. The plot of land on which the cathedral was to be constructed was called Merrifield, at first, anyhow.

It’s also argued that Salisbury, Old Sarum and Stonehenge lie along a ‘ley line;’ the best I can understand this is that the ley line is a more or less straight path through the landscape, either through land formations or, a ‘spiritual’ path. It’s possible. Look on a map, and you’ll find Salisbury on the south, Sarum two miles northwest, and further northwest from there, about 8 miles as the crow flies—in a more or less straight line—is Stonehenge.

Salisbury—Old Sarum—Stonehenge Ley Line. Source: Google Maps

Salisbury—Old Sarum—Stonehenge Ley Line. Source: Google Maps

Poore creates riches: In 1219 A.D. a wooden chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was constructed on the site of the yet-to-be built cathedral, and Bishop Poore celebrated divine service in it and consecrated a cemetery. Poore also then began arrangements, in earnest, for money to be raised for the cathedral at ‘New Sarum.’ Each of the canons and vicars was asked to give up a fourth of their annual incomes for seven years, and the nobility around guaranteed money for the next seven years. Preachers went far and wide with collection plates, with also the bribe of indulgences and pardons to those who either gave a gift or their time and labor toward building the cathedral. Everything had a price.

However, not everyone kept their promises. The clerics were perhaps the most delinquent, because Bishop Poore then decreed that if the canons and vicars did not pay the money within fifteen days of it being due, the corn on their lands would be seized and sold in the open market to make up the default.

The spectacular West Front of Salisbury Cathedral.

The spectacular West Front of Salisbury Cathedral.

Bishop Poore struck ground for Salisbury Cathedral on the 28th of April, 1220. People came from all over to witness and take part in this great event. Poore conducted a service, and then, accompanied by the clergy, he took off his shoes, and barefoot, walked the rest of the way to the place where the foundation was to be laid, singing the Litany. There, he gave a sermon, and laid the first stone in the name of the pope.

The second stone was laid in the name of the Archbishop of Canterbury; the third in his own name. The fourth and fifth stones were laid by the Earl of Sarum and his wife, Ela de Vitri. Others followed—nobles, Dean, chanter, chancellor, treasurer, archdeacons and canons of the church at Old Sarum. When the rest of the nobles returned from Wales, where they had accompanied King Henry III, they also laid stones on the foundation, and pledged money toward the construction. And so began that cathedral at Salisbury.

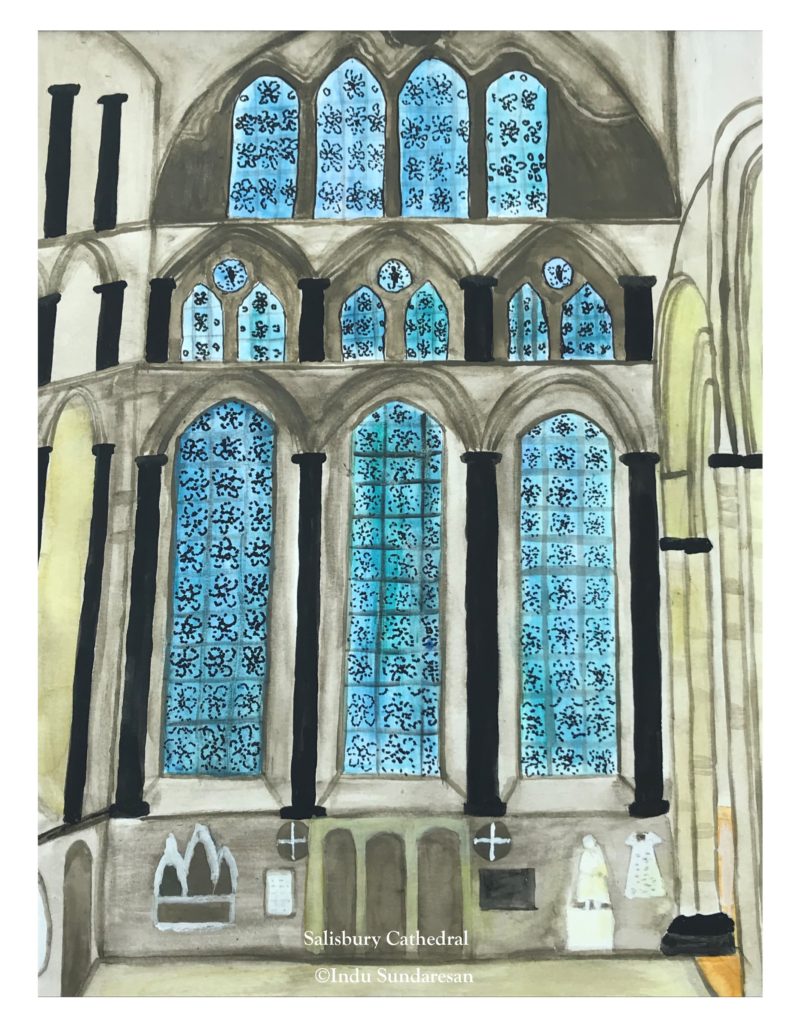

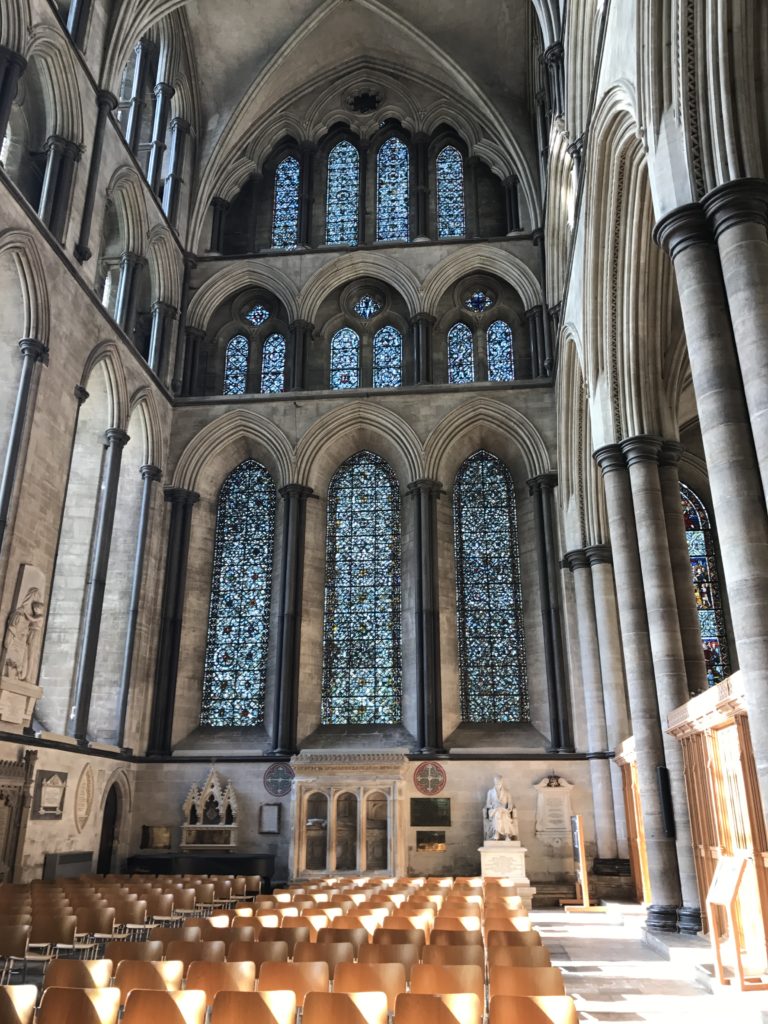

The North Transept in Salisbury Cathedral.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—The new Cathedral rises—Salisbury Cathedral—Part 2

I thoroughly enjoyed this elegantly told history of Old Sarum and its “translation” to Salisbury Cathedral. How refreshing to read such a rich and detailed post. I had high expectations knowing Indu Sundaresan’s riveting historical fiction novels, but I have to say this topped them. I hope there will be more video introductions ahead and more witty moments of learning and laughter–“Poore creates riches.”

Thank you, Janet! Means a lot that you say so!

Great start, in your own style. Keep it up. Do you plan to move on to historical novels based on English/ European history soon?

Good luck.

Thank you! Haven’t given a thought to that yet, Vasu.

all the info i read it in one breath, it was like a story! nice writing as usual! ^_^

Thank you!