(Part 1 here)

What is it? What was it used for? Circles beget circumambulation, and so several guesses have been made that it was part of the ritual at the stones. This, going around as a form of prayer, is still present in Hindu temples and ceremonies. It’s called Pradakshina (Sanskrit for ‘moving to the right’), and in temples, devotees set off on a clockwise path around the deity, or brides and grooms around the sacred fire during a wedding ceremony.

The Stonehenge stones are also arranged on a northeast/southwest axis in line with the midsummer and the midwinter sun—on the day of the summer solstice, the sun rises and strikes the northeast entrance to the stones; on the day of the winter solstice, the sun sets at the southwest point of the circle. Stonehenge has been dated (at its earliest) to the end of the Neolithic period, around 3000 BCE, and construction continued for a good 800 years after. If the stones stand today, more or less as they were composed some five thousand years ago, with that northeast-southwest axis, then the reasoning is that Neolithic man knew something about the sun, the moon and the stars. And they followed the path of the sun, and understood what the summer and winter solstices were. So, it’s an observatory of some kind? Something that allowed Neolithic man to track the movement of the sun?

And, other evidence leads to another theory: Skeletal remains of humans and animals have been discovered at Stonehenge, leading to the hypothesis that it was either a burial ground, or that humans and animals were sacrificed there, again, as part of some sort of ritual. But, it dates distantly enough in historical time—when no records were kept of its use—that nothing about the actual ritual is known for sure.

There are several other ‘henges’ in this part of England in Wiltshire, most notably the bigger (larger circle) henge at Avebury. Like Stonehenge—and the construction of the Avebury henge is contemporary to Stonehenge, with the same dates of construction, about 3000 BCE to about 2400 BCE—Avebury has a large ditch around the outer circle of stones, and two inner circles of stones. The village of Avebury was first laid out sometime in the Middle Ages, outside the henge, and then crept into the henge, as it is today.

The henge at Avebury, Wiltshire. Source.

The existence of Stonehenge and the Avebury henge, and the dating of their antiquity, is primary evidence that by this Neolithic era, around 4000 to 3500 BCE, early man in Britain had transformed from the hunter-gatherer to the agriculturist, settling in the valleys, clearing the land and transforming it into fields, and staying in one place. The henges also point to a fairly stable—and successful—economy. If the henges were used for religious or ritualistic purposes, given their sheer size and the weight of the stones, Neolithic man had enough leisure to pursue the building of the henges, and was productive enough in his agrarian work that he could devote time to this.

Stonehenge today; making sense of what you see: A circular ditch is the first approach to the stones. The ditch and the bank around it are what make the ‘henge.’

The ditch around the stones at Stonehenge.

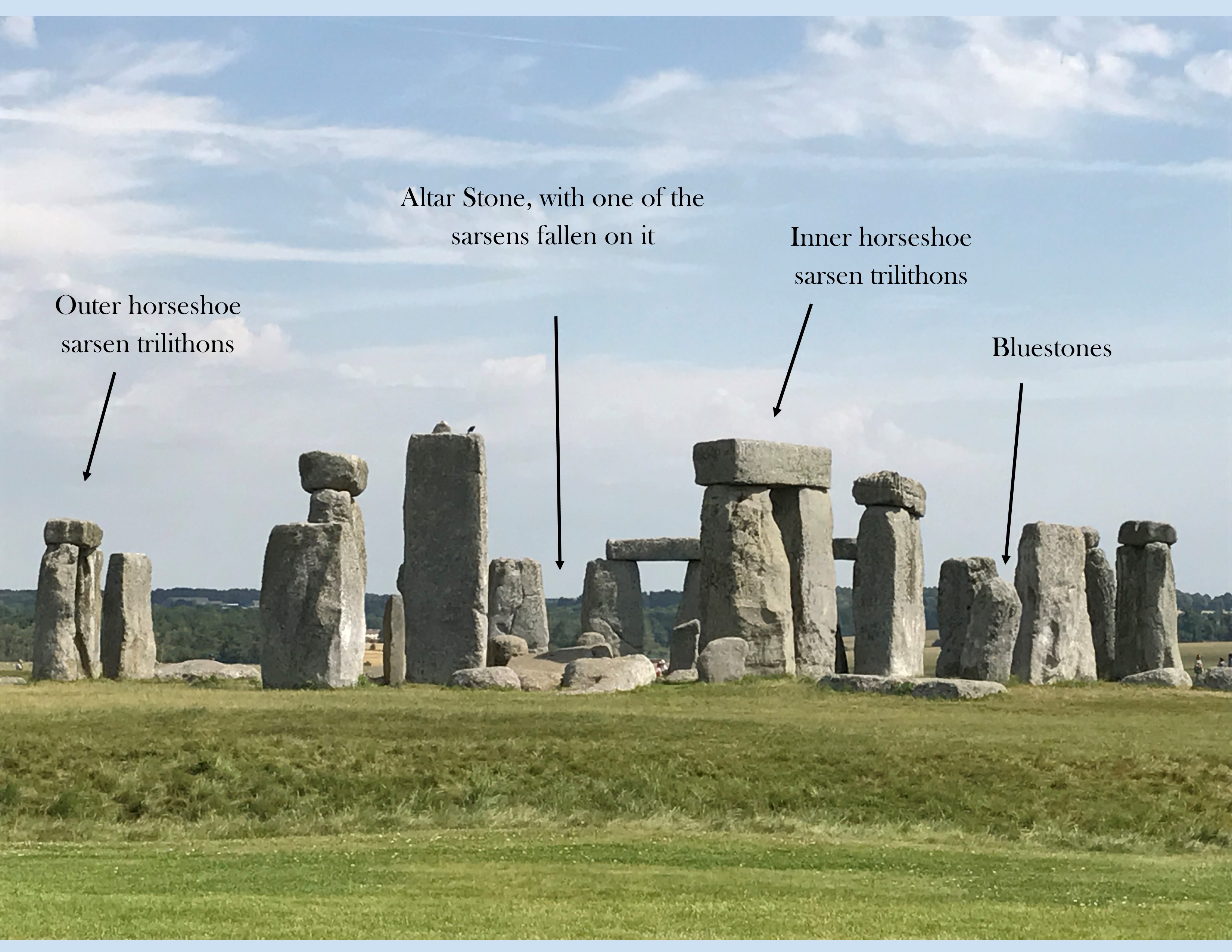

The mammoth outer stones—in the form of a horseshoe—are sarsen stones, a silica sandstone, and they’re the most visible. The sarsens are shaped in the form of trilithons, which is two upright standing stones, crossed over on the top with a lintel.

Sarsen stones.

There’s also an inner horseshoe, also formed of sarsens in the shape of trilithons. Five trilithons were raised originally, and today only three still stand. One of the fallen trilithons is now over the altar stone, set wide in the ground, its width facing the northeast entrance to the circle, so presumably, the rising sun on the summer solstice would strike the altar stone.

Within the outer sarsen horseshoe are also a series of bluestones, smaller stones in a circle near the inner sarsen horseshoe. While the sarsens are plentifully found in Wiltshire, so, sourced locally, the bluestones come from 200 kilometers away in Wales. The bluestones are indeed ‘smaller’ than the sarsens but weigh three or four tons each, and this was before, or about the time the wheel was invented. Or rather, the wheel was probably in existence when Stonehenge was raised, but elsewhere in the world—there’s no definite proof that it was used in England. How then did Neolithic man bring these bluestones from as far away as Wales? That’s a conundrum, and one theory to explain this is that the bluestones were found in Wiltshire after the glaciers receded after the Ice Age.

The sarsens weigh close to twenty-five tons, and closely sourced or not, they still had to be moved to the Stonehenge site. It boggles the imagination, that in prehistoric England, man managed to shift such mammoth stones before the use of the wheel.

And then, there’s that whole alignment on the northeast/southwest axis. If you visit Stonehenge today, on that broad earthwork avenue leading to the northeast entrance is a solitary upright stone called the Heel Stone or alternatively, the Sun Stone—because the sun on June 21st rises over this stone before the light enters Stonehenge. And the Heel Stone sits in the middle of the avenue that people walked on to enter the site. Also, anyone standing at this point on the winter solstice will see the sun setting on the southwest end through the stones.

So, it’s an astronomical wonder? Constructed in a country famed for its cloudy skies, its lack of sunshine, and by prehistoric man who had just about graduated from his hunting-gathering days to becoming a stay-in-one-place-agriculturist? And yet, he was curious enough about the sun, the stars, and the solstices? Prehistoric man certainly built Stonehenge—its dating is in little doubt. But why? And how?

And, the news about Stonehenge keeps coming: About two weeks ago (from the date of this post), a new study was published in Scientific Reports about the possible origin of the human remains found at Stonehenge.

These remains were discovered in the 1920s, in a series of 56 pits around the inner circumference of the stones. They’re called the Aubrey Holes, named after John Aubrey, who first noticed the pits in the 17th Century. The bones were buried in leather bags in the pits, but after the dead had been cremated. After they were discovered in the 1920s, the bones were all piled into Aubrey Hole 7 and buried again.

More recently, the bones were dug up and put through a series of analyses with new techniques of reading meaning into the remains. The conclusion, published in the Scientific Reports study, is that the individuals buried at the Aubrey Holes came from Wales, and were not local to Wiltshire—or at least, they had not lived in Wiltshire for more than ten years, or the analysis on their cremated bones would have shown evidence of local food and drink, and not that of the Welsh countryside.

While one of the uses of Stonehenge has long been identified as being a cremation ground of sorts, this new study now brings attention to the bluestones again. The Aubrey Holes are most likely the original standing places of the bluestones—so, was that then part of the burial ritual? For people from 200 kilometers away in Wales? They cremated their dead, and brought their bones and the bluestones with them from Wales to bury the bones and set the bluestones upright upon the remains?

Since the remains of the dead date to the early 3000 BCE construction of Stonehenge, how did this Welsh Neolithic man move the bluestones, which weigh about three or four tons? There are still many questions without answers, but some answers now, with this latest study, which provide a sort of clarity. Of one part. And, raise more questions!

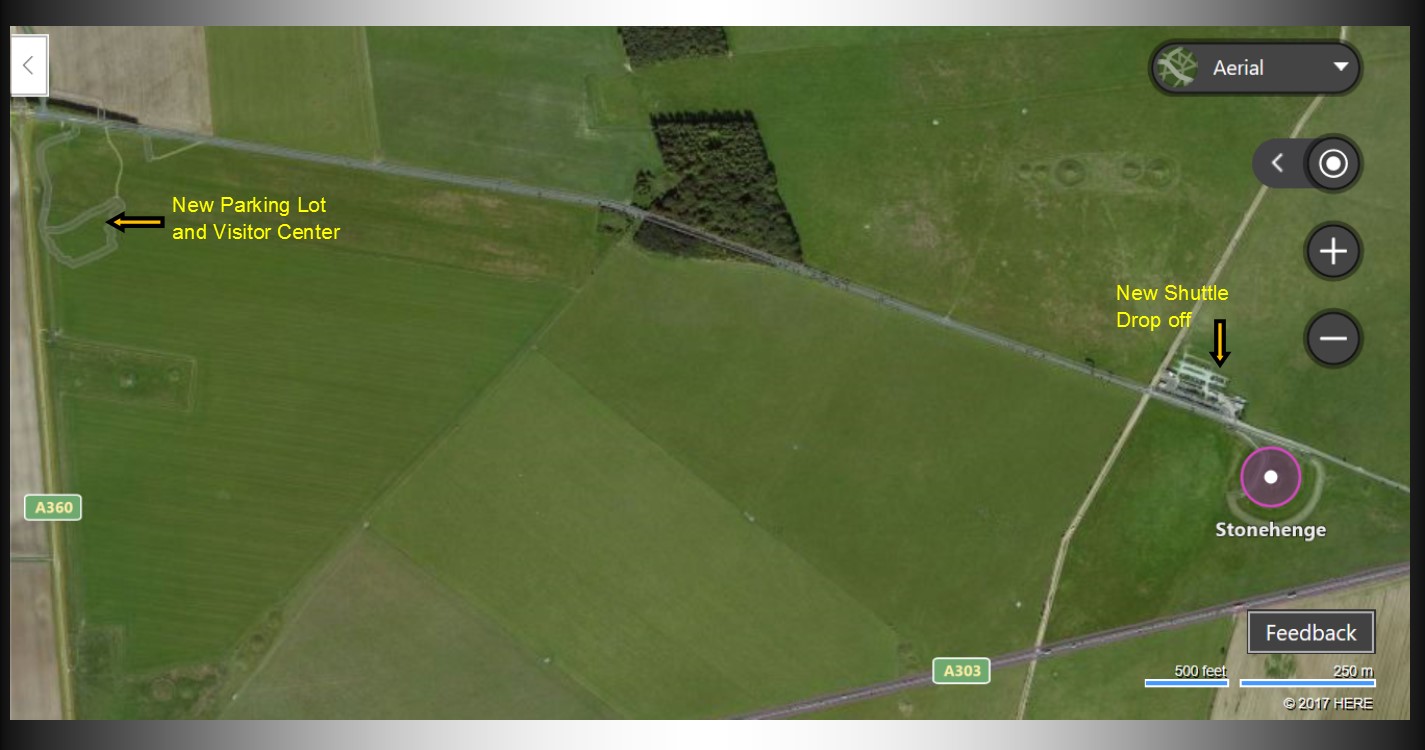

Source: Bing Maps

Visiting Stonehenge today: I wanted to look at an aerial view of the monument as I was writing this blog, and curiously enough, Bing maps shows an aerial view that dates, by my counting, to some four years ago, before the new visitor center was built. Look at the screenshot I took of Bing Maps, the view of Stonehenge. The old parking lot was obviously right next to the stones, marked as ‘New Shuttle Drop off’ on the map. But the new parking lot is much further west, near the new visitor center, marked as ‘New Parking lot and Visitor Center’ on the map. You can see the A303 just south of the stones—that’s still there, and it runs very close to the monument. Originally, I think, the road east leading to the stones went all the way to meet the A303, but it’s cut off now—there’s no access to the stones from the east at all, only from the west. And, you have to park at the new visitor center, get on a shuttle bus, and get dropped off at that old parking lot right next to the stones.

We headed east from Stonehenge into Jane Austen country on the day we visited, and as we drove on that road below, the A303, there’s a beautiful view of the stones. It doesn’t show up that well in the picture I took from the car, and looks much better in person. I think you still should get up close to the stones, gauge their size, and marvel at this feat of engineering.

View from the A303 highway, eastbound. The highway is divided here, so perhaps you won’t see Stonehenge from the same point, driving west.

Stonehenge contemporaries: There’s a consistent fascination about Stonehenge, not just for its antiquity, but also for its clear lack of identifiable purpose, for the conjecture on who built it, how they carried those colossal stones up and placed them upright, and what ceremonies were conducted within. There are other, equally ancient sites in the world, which speak of man’s prowess in building and providing us with a glimpse into how that man actually lived.

The Pyramids at Giza also date to this Stonehenge time period, involving dizzyingly high edifices using giant stones. And, an entire city, Mohenjodaro, was discovered in the 1920s in the flood plain of the Indus River. Mohenjodaro is magnificent, with assembly halls, avenues, a marketplace, wells for water, a university building, and public baths. We’re not talking agriculture as a mainstay; there was some other economy also, and definitely music and arts, so vast amounts of culture and understanding. Considering that the Indus Valley Civilization that existed more than five thousand years ago, this level of complexity is mind-boggling.

Mohenjodaro in Pakistan. In the foreground is the Great Bath; the Buddhist stupa is at the back. Source.

Stonehenge isn’t quite as sophisticated, but England was (still is!) on an island, and so Neolithic man would have been fairly insular. Because, simply crossing the choppy English Channel, for someone who wanted to migrate from the mainland to the island, or the other way around, would have been a life-risking attempt. Only once that was conquered with some modicum of success could there be the exchange of goods, and then ideas and engineering concepts. Mohenjodaro and Stonehenge could well have co-existed and there would have been no contact between the two peoples.

But, take into account Stonehenge’s alignment to the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset, and it’s puzzling how prehistoric man, confined to an island, could have known all this, or…how he knew this and future generations forgot it, and we have to now stab in the (relative) dark to discover what it was. Still, it’s history. It’s mystery. It’s an eternal fascination.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—I-think-I-went-to-England-for this!—the next few blog posts, we roam around Jane Austen country—to begin with—Not Northanger Abbey: Jane Austen, Steventon and the Church of St. Nicholas—Part 1

Very detailed and comprehensive account of the Stonehenge monument. As a lover of heritage stories, I like both the parts. If you don’t mind, let me point out a slippage in the first paragraph of the second part. The ‘pradakshina’ in Hindu temples and at wedding ceremonies is performed in a clockwise direction, not otherwise. Anti-clockwise movement is considered inauspicious.

I have great admiration for your ability to marshal a vast quantity of facts and present them cogently. I see it right through your books and write-ups. Incidentally, I have reviewed your book “The Mountain of Light” in my blog “Reflections in Tranquillity.” I look forward to seeing more posts by you. – Subbaram Danda, Author, Blogger and Freelance Journalist, Chennai, India.

Thank you for your kind words! You’re absolutely correct that the Pradakshina is performed in a clockwise direction. In my mind’s eye, I ‘walked’ in the correct direction, but obviously put it down incorrectly while writing. Thanks for the catch; I’ve made the change.