(Part 1 here)

A Space to Write: To any writer, perhaps the most important room in the house is the place to write. Hardy had three. In his original plan for the house, the ‘two up, two down,’ his first study was one of the ‘two up’ rooms upstairs, over the drawing room.

Left, Hardy’s First Study, above the drawing room. Right, Hardy’s Second Study, originally the guest bedroom.

At that time, even though the house was called a ‘two up, two down,’ there was a small guest bedroom behind the master bedroom which was over the original small kitchen on the ground floor. This later became his second study.

And later, during the 1894 additions, he built himself a third study behind the guest bedroom and over the new kitchen below (the old kitchen became a store room of sorts).  Hardy’s Third Study, over the new kitchen, after the 1894 remodel of the house.

Hardy’s Third Study, over the new kitchen, after the 1894 remodel of the house.

A staircase was added on this upper floor, to access the unused attic space directly above the master bedroom. The rest of the attic was already partitioned into bedrooms for the servants, and accessed by a different staircase from the ground floor, behind the main stairs. This new build included two tiny rooms and a landing and these became Emma’s rooms, where she read and spent the day. Hardy had his (numerous) studies in the house, and now, Emma had her own space also. Their marriage was perhaps already unravelling at this time; in any case, a few years after this, Emma moved out from the bedroom floor permanently, and into the attic rooms, leaving Hardy in sole possession of the master bedroom.

The master bedroom on the top floor, front of the house, left of the entryway.

The First Wife, Emma Gifford: Far from the Madding Crowd sparked Hardy’s reputation as a writer and gave him enough money to finally marry Emma after four years of courtship. Tess of the d’Ubervilles, that other, famous Hardy book, was published in 1892 and gave him, curiously enough, money to do the renovations to his house so that his wife—after the marriage had effectively ended—could live away from him in an attic bedroom. But, I’m moving too fast here from marriage to a semi-divorce; back to Emma…

Emma’s Attic Bedroom

Thomas Hardy met his first wife in 1870, within a few months, possibly, of ending his relationship with his cousin Tryphena. He was still working as an architect and travelled to St. Juliot in Cornwall, a tiny village with a church that was in need of repair. He bunked at the vicarage, and Emma was the sister of the vicar’s wife. It must have been something very close to love at first sight. By the third day, he was calling her, or at least referring to her by her first name. But, years passed after this first meeting, because Hardy had to return to Dorchester, and Emma stayed on in Cornwall with her sister. An actual marriage at that point was impossible—although she was socially above him, she was penniless, and Hardy was just beginning to establish himself as an author.

Thomas Hardy met his first wife in 1870, within a few months, possibly, of ending his relationship with his cousin Tryphena. He was still working as an architect and travelled to St. Juliot in Cornwall, a tiny village with a church that was in need of repair. He bunked at the vicarage, and Emma was the sister of the vicar’s wife. It must have been something very close to love at first sight. By the third day, he was calling her, or at least referring to her by her first name. But, years passed after this first meeting, because Hardy had to return to Dorchester, and Emma stayed on in Cornwall with her sister. An actual marriage at that point was impossible—although she was socially above him, she was penniless, and Hardy was just beginning to establish himself as an author.

St. Julitta’s Church at St. Juliot

Source: Steve Wheeler

They married finally in 1874, after Hardy had published two books, and begun to serialize a third, Far from the Madding Crowd—which would make his name, and fame.

Love’s ok…but marriage? Hardy and Emma had a long distance courtship, peppered with letters, true, but they had never really known what it was to get out of the honeymoon phase during those four years. Reality, living in close quarters, always with each other, under each other’s feet; that was different.

Emma was also a writer. From the distance of all these years—and, given Hardy’s gargantuan reputation—it seems absurd to us that two writers of any repute lived in the same house. How could anyone compete with Hardy? Yet, it was true. She considered herself a writer, had written before they met, and continued writing after. Hardy himself was offended by her presumption, and she in turn criticized his work.

Emma Hardy

There were other problems. The Hardys had no children, and they both wanted them. This sort of longing must have created a distance in their relationship. And, Emma had a contentious association with her in-laws—no one was present from Hardy’s side at the wedding, and it took a while before they met Emma. Jemima, Hardy’s mother, was the quintessential tiger mom; she kept her cubs close, and other than Hardy, none of her other children married.

In Victorian England, divorce was not a real possibility. Sparring spouses chose to either live apart, in different houses and cities, or, as Emma did, moved away physically from the marriage in the same house. Upstairs. In the attic rooms Hardy obligingly built for her.

Emma’s attic bedroom, left, and the tiny attic sitting room, right.

The Women in Hardy’s Life: Thomas Hardy had somewhat uneven relationships with the women in his life, with varying degrees of tumult. His paternal grandmother, Mary Hardy, lived with them at the cottage, in an addition built to the house when Hardy’s father married his mother. He went to her often for affection as a child, and as an adult to seek out history—his history, the history of the parish, the stories of the people. And then, put them in his books.

His mother, Jemima, was the dominant (and controlling) influence in his childhood; it was she who took him out of the village school and sent him to the one in Dorchester, a three mile walk each way. She was never happy about his marriage to Emma, perhaps, like his lifelong unmarried siblings, she would have preferred that Hardy had also remained a bachelor.

He was passionately in love with his first wife, Emma, at least in the beginning of their marriage. As heated as their initial romance had been, the latter years of their marriage were positively arctic, leading to Emma moving out and up to the attic rooms around 1899. And then, when Emma died, Hardy began his love affair with her again, writing poems about their earlier encounters, the magic that they had lost, but which he remembered fresh as though it had happened yesterday.

Hardy wrote ‘Beeny Cliff’ in March of 1913, just after Emma had died, remembering the early days of their courtship. Beeny is a small hamlet on the Cornwall coast about a mile from the inland St. Juliot, where Hardy had gone to work on the parish church. They must have just met, just newly fallen in love and from the poem, it’s evident that Hardy’s memory is clear as water, even though he was writing forty years or so after the event. The sunny March day when they took ponies for a ride along the coast, on the cliff. The sprinkling of rain that colored the Atlantic until the sun came out again. The waves crashing below the cliff. Their laughter and what they said to each other.

O the opal and the sapphire of that wandering western sea,

And the woman riding high above with bright hair flapping free –

The woman whom I loved so, and who loyally loved me.

What he never told Emma (possibly) of his memory of this day, he put down in this poem after her death. It was a fulsome mourning. He loved the woman more in death than he did in life. But, there was another ‘romantic’ interest in Hardy’s life already, by this time.

Florence Hardy. Source.

But, there was a second wife: And then came Florence Emily Dugdale, the second wife. She had written to Hardy in 1905; an admiring, gushing letter to a famous author. Florence would, in today’s parlance, be called a groupie. She started researching materials for him at first, then became his secretary and visited him when Emma was not around. Later, Emma grew fond of this young woman and befriended her, and Florence was then caught between the two, Hardy and Emma, in a sort of bizarre threesome.

Emma Hardy died in 1912, having lived more or less permanently in her attic rooms for the last fifteen years, and Florence moved into Max Gate a year later, first as a ‘housekeeper,’ and then, in 1914, she married Hardy.

The Bell Pull at the front door of Max Gate. Original, I think.

This late-in-life relationship of Hardy’s was another curious one. He was in his seventies, Florence in her thirties. He was aging, and ailing, and she, still starstruck, was more a helpmate than a wife. And, during the time that Hardy was married to Florence, he was belatedly declaring his love for Emma in his poetry, tracing each step of their courtship all those years ago, how she looked, what she said. Falling in love with his first wife all over again, while leading that young ‘un to the altar. It must not have been an easy marriage for Florence.

Hardy could have been a Butcher, a Baker…an Author? Whatever turbulence Hardy encountered in his personal life, especially with the women, he was a steady, working writer—his published novels attest to that. No matter what else was happening, he shut it out, put his head down and wrote, and created worlds peopled with characters who still live today through his words. Bathsheba Everdene, Gabriel Oak, Tess, that mayor of Casterbridge. These, and others, depending on how you’ve read your Hardy.

I can’t remember now where this window is in Max Gate…perhaps, from the orientation, on the corridor leading to the Third Study, part of the 1894 remodel.

How did a man, born to a builder, apprenticed as an architect, become one of the world’s best known novelists? Although Hardy’s family were not of the gentry (unlike, say, Jane Austen or the Brontë sisters—daughters of clergymen), they were a sort of upper class tradesmen. They didn’t own their family home—the cottage in Higher Bockhampton—outright; it belonged to the local lord of the manor. But, they had a life interest in it, a long term until-death lease, which was renewed at least from the first Thomas Hardy grand-père to Thomas Hardy, père. So, they were stable, not itinerant laborers.

And, Hardy’s grandfather was an elector in the parish, entitled to vote in the parliamentary elections (again, that privilege that the (other) treasonous Thomas Hardy fought against; see Part 1 of the Max Gate post), and played the music for the church services. Hardy’s maternal grandmother, and his mother, were possessors of books—a fine and expensive commodity at that time. Education was encouraged in the Hardy household. Although he grew up with a delicately tuned ear to the Dorset dialect which he replicated so ably in his novels, he grew up educated, well read, curious and ambitious. He was, in other words, primed for his eventual profession.

Max Gate. What you see is the front entryway (left) and the rooms on the right are the drawing room below and the First Study above. At the very right is a glimpse of the conservatory Hardy added on in 1913, after Emma’s death and before he married Florence.

Max Gate. What you see is the front entryway (left) and the rooms on the right are the drawing room below and the First Study above. At the very right is a glimpse of the conservatory Hardy added on in 1913, after Emma’s death and before he married Florence.

Even so, Hardy wasn’t a mean architect. His work still remains, in Windsor and at St. Julitta, the church which he went to restore when he first met Emma, and many other places. He could have made a decent, solid living as an architect—it must have crossed his mind, this, when he was being rejected by publishers for his early books. Although Thomas Hardy wasn’t also that other one, tried for treason, and who shows up in a search of his name, our Hardy, the novelist, had much of the same compassion for the common man and his rights, which shows in his writing. Thankfully for us, Hardy became a writer, a published author able to support himself by his work, and able, to write more.

Thomas Hardy died in 1928, when he was eighty-seven years old. His family wanted him buried locally, but there was a push to bury him in Westminster Abbey in London. They reached a compromise: his heart was taken out and buried in the churchyard of St. Michael’s church in Stinsford—where he was baptized; and his ashes were buried in the Poet’s Corner in the Abbey.

Thomas Hardy’s heart is buried at St. Michael’s Church, Stinsford. Source.

I read most of Hardy’s novels in my teens. And, some hundred and fifty years after he built Max Gate, I visited the house that he designed and lived in and wrote in. It was something awesome for me. In my little corner in India, Hardy introduced me to his bit of the world, to his fierce and passionate heroes and heroines, to the lush land, to the cold snows of the winter, to the troubles that roil our hearts.

We visited a few other writers’ houses (you’ll come with me in future blog posts) in England and it’s a wonder to me that they have survived, that no one thought to demolish them and build spanking new steel and glass apartment complexes on the land.

Max Gate is probably not much like it was when Hardy lived there, or even, when we visited. One of the curators said, “It’s an unusual day.” It’s true, I think. Warm and sunny, light flooding into the house, very un-English weather. During Hardy’s time, it was probably cold without central heating, and what little light might have been, was slaughtered by the close growing Austrian pines.

But, Max Gate is still a part of history. I’m grateful it exists, so I can stand by the window and imagine Hardy at eighty, shuffling to the armchair by the fireplace, or even the younger Hardy, filled with pride at this house, the fruit of his writing labors. Hardy’s lived and gone now, but his house remains, a little, tangible piece of the man who was a lion of literature.

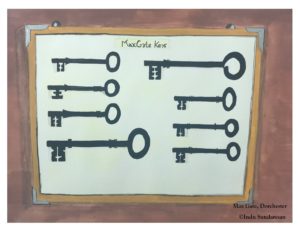

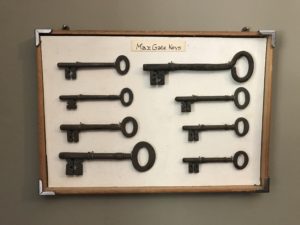

The original Max Gate keys, displayed at the house.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—I have a bit of fun writing fiction, because how would anyone know of anything so far back in time—Standing in Time—Stonehenge—Part 1

Hi Indu,

Your post is dazzling. Reading it made me feel as if I was also visiting Hardy’s house (which I plan to one of these days) – I was so engrossed that I felt almost sad when I reached the end. Thomas Hardy has been a favourite author of mine, and like you I used to read his books in India since we had a large library at home. Out of all the novels, Jude the Obscure, will always have a special place for me – I simply love the story.

Thank you for writing this piece. Also, thank you for writing the stories that you do, the book covers fascinate me almost as much as the material inside. Do keep writing and delighting your readers.

Hi Purabi,

Thank you for your kind words! Visiting Max Gate was a lovely experience–I walked around, and thought of Hardy’s novels. Like I said in the blog post, I’m grateful it exists, and awed by how well the English preserve and curate their historical homes (my interest was mostly in the writers’ houses) and how accessible they are to everyone.