Jane, her sister Cassandra, and their mother moved into Chawton Cottage in 1809, thanks to her brother Edward Knight’s generosity. One other person came to live with them. Martha Lloyd was a longtime friend, and a few of Jane’s surviving letters are written to her. She was the sister of Jane’s oldest brother James’ second wife, Mary. Got all that? (James took over the rectory at Steventon when their father retired; his son by his second wife, James Edward Austen Leigh, is the one who wrote Jane Austen’s first official biography. So both Martha and Jane were aunts to James Edward Austen Leigh).

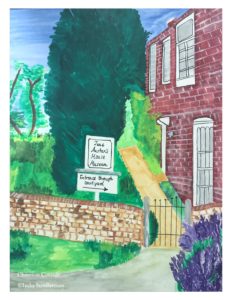

Chawton Cottage, from across the street, near The Greyfriar pub.

I haven’t mentioned Jane’s friends much in the previous blog posts, even though Martha was very much present in her life during the Steventon, Bath and Southampton years. It was a long and enduring friendship, akin to sisterhood for Jane, something she mentions in her letters.

Martha Lloyd was one of the daughters of Reverend Lloyd and his wife, née Martha Craven, whose father, Charles Craven, was governor of South Carolina for about four years. Marrying a country curate may have been a social step-down for Martha Craven, but, by all accounts, the Lloyds were happy together. The Austens and the Lloyds were longtime friends, perhaps Jane’s father George and Noyes Lloyd made the first connection—it’s not known how or where. When Reverend Lloyd died in 1789, George Austen offered the Lloyd women a place to stay, at the old rectory in Deane. (George Austen, if you remember, was rector of both Deane and two-miles-away Steventon, and moved to the rectory at Steventon before Jane’s birth).

Chawton Cottage from the back. The door you see is from the room behind the dining room, next to the stairs. The next picture is the room from the inside. The window upstairs, in the first photo, is from the bedroom that Jane and Cassandra shared.

Perhaps that intense friendship between Jane and Martha Lloyd began then, when they lived so close to each other. Martha’s sister Mary was more of Jane’s age; Martha was a whole ten years older, and yet it was these two—at fourteen and twenty-four—who became close.

This Austen-Lloyd connection, begun here, never really ended. Jane’s brother James married the younger sister Mary as his second wife, and they had two children together. When her mother died, Martha more or less moved in with the Austens. They spent some time together in Bath, and when George Austen died in 1805 and the Austen women were on the move, Martha traveled with them. She even went to stay at Jane’s brother Frank’s home in Southampton, where they lived with Frank’s wife because he had gone to sea. It was an arrangement that suited everyone—Frank was a sailor and away for most of the year, and his wife was pregnant and needed company.

Frank Austen, in early life, and Martha Lloyd in late. Source.

Frank’s wife died a few years after Jane Austen, in 1823. Five years later, he led up the altar the woman who had been a constant in the lives of his sisters and his mother. Martha Lloyd was sixty-two when she married Frank, who was knighted by now, and who made her Lady Austen.

The gift of Chawton: It was another of Jane’s brothers, Edward Knight, who gave Jane a place to live in permanently. Edward, if you remember, had been adopted by the wealthy Knight cousins (see Part 2), and he made them the offer while they were in still in Southampton in October, 1808. Cassandra was at Godmersham Park—Edward’s seat—helping out when his eleventh child was born. All was well for a while, and Jane wrote her congratulations, but soon after, Edward’s wife died. About a week after the funeral, in the midst of his grief, Edward told them that two places had come empty on his estates, one near Godmersham Park and another near Chawton House. They decided on Chawton Cottage, sight unseen, because it was back in their old neighborhood—Jane’s brother James, now rector at her old home of Steventon, was only fifteen miles or so away. And, although they didn’t know it then, they placed Chawton Cottage firmly in history.

This is the front of Chawton Cottage. The front door is not used today, entry is instead through the gate on the right. Note the bricked up window of the parlor, left of the door—Edward had that done, to give them privacy from the main road. Source.

The cottage was set on the grounds of the estate of Chawton, one of Edward Knight’s inheritances from his adoptive parents. It’s on a curve of the main road, and flush up against the road. The gardens are to the side and behind. From its location on the village road, and the lack of an actual front garden, it’s obvious that it was built originally as a pub, and before Jane Austen moved into it, Chawton Cottage was the home of Edward Knight’s steward.

Edward made improvements in the cottage. The dining room and the drawing room windows faced the street, and were so close to the road that anyone traveling by could look in at the Austens. The drawing room window was bricked up so now they had privacy, with daylight coming in from the side and a view of the side garden, the high fence and a hornbeam hedge that kept traffic out of sight on the Winchester road.

The cottage is at the very end of the village, and just beyond the side of the building, the road curves to Winchester to the right, and on the left, Gosport Road leads to Chawton House (which also belonged to Jane’s brother Edward) less than half a mile away—about the same distance Jane walked every Sunday from the old rectory at Steventon to the church where her father conducted the services.

Chawton House, down the road from the cottage. Source.

Chawton House also still stands today—it’s called Chawton House Library—and is a venue for literary events, and, as the name suggests, houses a library. All grand manors had much-coveted libraries. Books were an expensive commodity in pre- and Victorian England (the Brontë sisters, north in Yorkshire, devoured books from their richer neighbors). Jane undoubtedly made use of the Chawton House library, whether Edward (who lived principally on his other estate at Godmersham Park) was in residence or not.

There’s an omnipresent pub, called The Greyfriar, opposite Chawton Cottage today, which was also probably there in the early 19th Century.

The Greyfriar pub in Chawton. The red brick cottage where Jane Austen lived is on the right, across the road. Source: Google Street View.

The name of the pub is a nod to Edward and his Knights, because the Greyfriar was the family crest. The Greyfriar is a Franciscan monk, and there’s a figure of the monk above the Knight coat of arms and plentifully to be found around Chawton House. It’s not clear why the Knights (presumably well before Jane’s brother, Edward, was adopted by them) chose this for a family crest.

This plate (set on the dining table in Chawton Cottage) comes from a dinner service set that Edward and his daughter Fanny, accompanied by Jane, bought at Wedgewood’s in London in 1813. Jane mentions this in a letter to Cassandra “…the pattern is a small lozenge in purple, between lines of narrow gold, and it is to have the crest.” It does, but darn it, you can just about see the Greyfriar at the top of the photo. I didn’t know then that I would be talking about Edward’s family crest in the blog, else I would have taken a better photo.

In Jane’s time, at that fork in the road leading to Winchester on the right and Gosport Road on the left, there was a pond. A horse pond, they called it. That doesn’t exist anymore. And, the view that Jane saw out of the front windows, either from the dining room or the parlor, must have been very different also.

This is what Chawton Cottage most probably looked like when Jane Austen lived there. On the left, displayed at the cottage, is a photo of a contemporary watercolor, horse pond and all. On the right, perhaps a more accurate portrayal of the cottage c. 1904, from Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Chawton is about Jane Austen. The old rectory at Steventon doesn’t exist anymore, only the church does. You can see 4 Sydney Place (in Part 1) in Bath, where Jane lived upon first arriving at that place. But here, in Chawton, is finally a house where she lived which you can walk into, wander in rooms, dwell in the garden, and drink in the atmosphere.

The side garden is to the left, the view from the parlor was toward this. The tradesmen’s entrance was on the right, through the gate. That is how you enter today. Source: Google Street View.

The side garden is to the left, the view from the parlor was toward this. The tradesmen’s entrance was on the right, through the gate. That is how you enter today. Source: Google Street View.

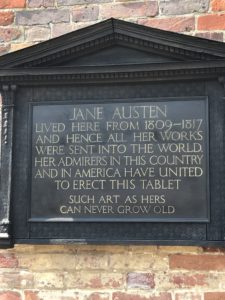

In this street view from Google maps, you see that the cottage’s front door is flush against the wall, and opened out into the street. Today, there’s a bit of pavement and grass in front, but in Jane’s time, it would have been a busy road as the traffic passed by to Winchester. A plaque on the left of the front door, just past the window, acknowledges Jane’s readers and their donations to keep her memory alive, from England and from America.

She sat most mornings in the room on the right of the door—the dining room—and here she wrote every day, hiding her pages from everyone, servants, callers, friends, not wanting them to know that she was writing.

The front door opened into a small vestibule—today, there’s a portrait of a young Edward, Jane’s brother, owner of the cottage and the lands, over the mantle, the doorway to the dining room on the right, and that to the parlor on the left. A creaking swing door covered the doorway into the dining room, and Jane didn’t want the creak fixed; it warned her to put away her papers when someone came to visit.

Edward Austen. This portrait hangs above the fireplace in the front vestibule. The doorway you see beyond leads into the dining room, where Jane wrote on a little table most mornings.

The main entrance into the property is to the right of the house, that large gate which led originally to the servants’ and tradesmen’s entrance. You go in, walk around the back to the left of the house and enter through a new door in the parlor, pass through the parlor, the vestibule, into the dining room, and access the stairs behind the dining room to the upstairs etc.

There’s a building in the back garden, possibly the stables in Jane’s time, where they kept their carriage and horses. It also houses a coal cellar with its distinctive slanted doorway and just outside, a well for their water.

The coal cellar, left, and the well, right, in front of the stables in the back garden at Chawton Cottage.

Also at the back is the bakehouse—the kitchen was attached to the house (we’ll get there next) but the baking, and salting, curing and smoking meat to preserve it was done here. Breads and pies were baked in this oven, and they boiled water in huge vats here to cook the meat.

The bakehouse at Chawton Cottage.

Around the left side of the house are two doorways—the first, farther from the road, is the kitchen. There’s a huge fireplace where most of the cooking would have been done. A door inside the kitchen led into perhaps the backstairs for the servants and a vestibule, which the servants had to pass through to take the food into the dining room. Today, you can only enter the kitchen from the outside.

The Chawton Cottage kitchen door is the first door on the picture on the left; the second door leads into the parlor. Today, this is the only access into the kitchen. In Jane’s time, the inner door from the kitchen to a back vestibule would have been used to take food through to the dining room.

And then, into the next door, closer to the main road, and into the parlor.

The wallpaper in the parlor of Chawton Cottage.

We visited a few writers’ houses while in England—Hardy’s in Dorchester we’ve already been to in this blog (Part 1 here and Part 2 here)—and I do remember that the curators took a great deal of trouble to recreate the homes as best as they could, into what they looked like when inhabited by the writers. At Haworth Parsonage, the blue-grey on the walls was the same color Charlotte, Emily and Anne Bronte saw when they lived there. Here, at Chawton, I think (I’m not sure) that I took this picture of the wallpaper in the parlor because a curator in the room mentioned that they had found a piece of the pattern while remodeling and had it recreated. If that’s indeed true, then this lovely, pale yellow paper was on the walls when Jane Austen lived at Chawton.

The piano in the parlor. Jane practiced faithfully every morning, before breakfast. Source.

Here also is a Clementi piano, much like the one Jane must have owned at Chawton Cottage. She mentions this—the pleasure of having a piano at last after all of their moving around in Bath and Southampton—in writing to her sister Cassandra, that Chawton meant a big enough space, a big enough parlor for a small piano on which she could practice country airs and watch her nephews and nieces dance. The curator in the room says, play it if you like. And so, the kid jumps on the chair (as she did at Hardy’s house in Dorchester) and plays ‘Fur Elise’ again.

Jane’s father George Austen’s original bookcase and desk, also in the parlor at Chawton Cottage. My impression is that it wasn’t actually here when Jane lived at Chawton, but has been brought into the space since.

The bookcase and desk in mahogany belonged to George Austen—it’s a piece of furniture Jane must have known well, because it came from the old rectory at Steventon, a house where she grew up.

Parlor window; the one facing the front of the house was bricked up, this one looks into the side garden.

Edward had the front window of the parlor, which looked out into the main road, bricked up for privacy, so the remaining window has a view of the side of the house, into the side garden and the road that leads to Winchester—now, the view was private and restful, the grass and the flowers in summer would break up the sight of the traffic on the road; the hornbeam hedge would shut out the noise.

Through the vestibule then, with its portrait of the young Edward Knight and into the dining room. All the rooms in the cottage are small, the floors are bare, quite possibly in Jane’s time, they weren’t carpeted much either. Every room also has a fireplace, a necessity when there’s no central heating. If I remember correctly, this is the table at which Jane and her sister, mother and friend Martha Lloyd took their meals.

If you scroll back on this post, you can see the ‘purple lozenge’ pattern that Jane describes on three of the pieces on the table, which comes from the dinner service set that Edward Knight and his daughter, Fanny, bought at Wedgewood’s in London in 1813. Jane accompanied them during this purchase. The set was ordered, and was to be delivered to Edward when Wedgewood had put the Greyfriar family crest on it.

The window looks out into the road from the village, and in a letter to Jane, her niece (Edward’s daughter, Fanny Knight) writes that as the commercial coach passed by their cottage, a gentleman looked in and saw them seated at a cheery breakfast!

The dining room window looks out onto the main road, and The Greyfriar pub across the street.

In the dining room, Jane revised her early novels and wrote her new ones. On this little table and chair, it is said, which went to an old servant and was brought back to Chawton Cottage after a great many years. (This is true of other pieces of furniture in other writers’ houses also—when they died they left the chairs/desks to their help, and then the curators chased these down from their children and grandchildren and brought them home again).

Tucked away into one corner of the dining room is this little desk and chair, where Jane Austen wrote her novels. For me, it was a little surreal standing there, looking down upon this. It’s possibly the most important connection to Jane Austen among all the places she visited, the houses she lived in, the room where she slept, the church where she prayed…here is the actual desk.

Beyond the dining room is doorway leading to the stairs and the second floor. The house is tiny, and the stairs appropriately narrow, but the landing pauses for a while to look out the window into that lovely garden at the back.

Upstairs, on the left and at the back of the house, is the room that Jane shared with Cassandra during the eight years that she lived at Chawton Cottage. There would have been two beds here, tent beds they call them, with that cloth canopy to keep out the cold at night. One closet on the left has a mirror and a washstand, and the closet on the right was for their clothes. There’s a fireplace in this room also—there was one in every room of the house, including the vestibule. The room looks out at the stables and the bakehouse.

The other rooms upstairs were for their mother, their friend Martha Lloyd, a small servant’s room and a guest bedroom.

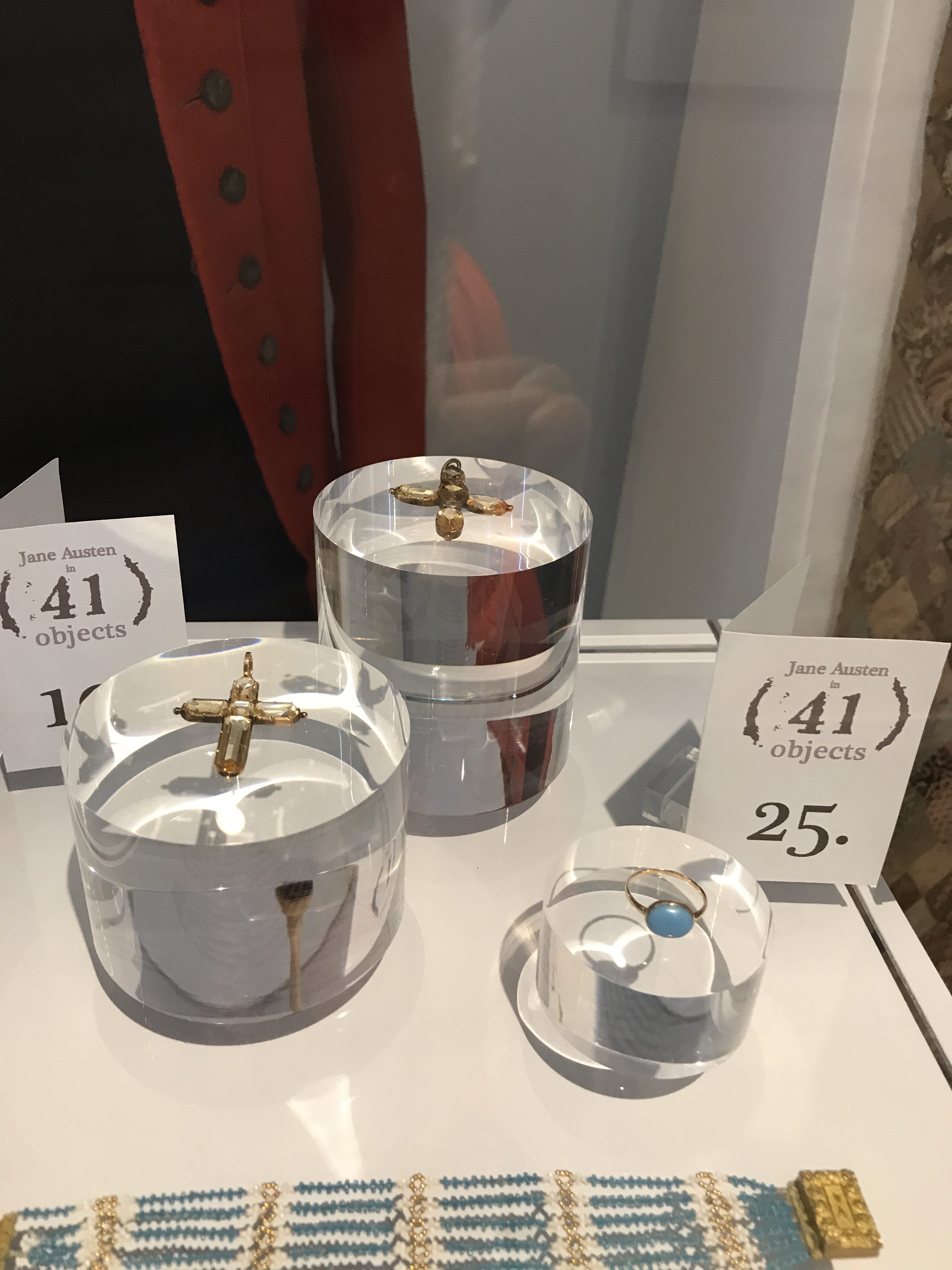

Displayed in one of the rooms are the topaz crosses that Jane’s brother, Charles, bought for his sisters with his first ‘prize’ money in the navy—she used this incident in Mansfield Park, when Fanny Price gets an amber cross from her similarly naval brother, but she doesn’t have a chain, and the detested Miss Crawford offers Fanny a chain, and Miss Crawford is in love with our hero Edmund, or rather he’s in love with her, and Fanny’s in love with him…so naturally, Fanny doesn’t want Miss Crawford’s chain. But, there’s another plot twist, because the chain comes not from Miss Crawford, but Mr. Crawford, her brother, an unrepentant rake who is determined to make Fanny his own. You see? One small gift from Charles grows into a pivotal plot point in a novel. Think of that, when you visit Chawton Cottage and gaze upon Jane’s topaz cross.

The cross in front is Cassandra’s and the one at the back was Jane’s. The turquoise and gold ring also belonged to Jane Austen. It has a bit of (more contemporary) dramatic history involving a sale to an American singer, and a return to England and Chawton Cottage. Look that up, if you wish.

The garden behind and to the left side of the house is large, although perhaps not quite as big as the one at the old rectory at Steventon, which had a rolling terrace, a vegetable garden and a ‘wood walk,’ a little knot of trees for shade and benches for sitting. But, the Chawton garden, the way it looks today and most probably in Jane’s time, is beautiful. Lawns edged with flower beds bursting with flowers, trees casting dabs of shade, and wooden benches to sit on and contemplate nature. It would have been enough for Jane, this little patch of land, after the years living in lodgings at Bath without much green to look at.

Mrs. Austen, their mother, let Jane, Cassandra, and Martha run daily life at Chawton Cottage and occupied herself with needlework and gardening, planting and digging up potatoes in the kitchen garden, and embroidering with some skill. Jane helped Cassandra oversee the servants and the cooking, and wrote. They all read, naturally, and also visited the poor in the neighborhood and taught reading and writing to their young.

Chawton Cottage brought a writing peace to Jane, something she hadn’t had since they had left Steventon. She was older now, and had also seen much more of life, fashionable or otherwise. Good friends and family members had died; they had knocked about their little world from lodging to lodging, and while all that didn’t move her pen, it fed her brain and her soul. And, when she began to write again, here at Chawton, she brought all her experiences to bear on her novels, old and new.

They moved into Chawton Cottage on July 7th 1809 and by April 1811, Sense and Sensibility was at the printers and she was editing Pride and Prejudice.

Sense and Sensibility was published later that year, and, as was usual at that time—especially with an unknown author—she paid for its publication. By 1813, that first print run had sold out and Jane was richer by a profit of a hundred and fifty pounds. Finally, at Chawton, Jane Austen realized her dreams of becoming a published author. Her book was read by others, people she didn’t know—not anymore just within the family circle—and they demonstrated their liking of it for paying her for her work.

Sense and Sensibility was published anonymously, as was also usual for that time, ‘by a Lady.’ Thomas Hardy, writing much later, and as a man, put his name on his books from the beginning. The Brontës, also writing later than Austen, used pseudonyms. That was the world then. Women didn’t quite attract attention to themselves, even if they were possessed of this sort of genius.

Chawton Cottage was Jane Austen’s home for the last eight years of her life. It was always filled with guests. Her numerous nephews and nieces came to visit during their holidays, friends were always welcome, and when Edward and his family stayed at Chawton House, the cottage folks went there often.

It’s a wonder to me that Jane managed to write at all, given all this activity. But, she did, every morning, after practicing the piano before breakfast. The children left her alone for a few hours, in the afternoon she was theirs. She played with them, brought out clothes from her closet to play dress up, and they read aloud to each other.

By the middle of 1816, Jane had finished Persuasion, but by then, she was also ailing and unwell. It got so bad in 1817 that her sister Cassandra accompanied her to Winchester, to see a doctor there. This was in May.

Jane Austen never came back to Chawton Cottage from Winchester. By July, she was dead.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next blog post—we take a bit of a break from Austen and go to a Brontë—Book Review—Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

One Reply to “At Home at Last: Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage—Part 3”