(Part 1 here)

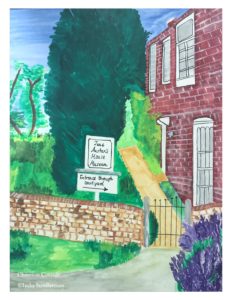

The front of Chawton Cottage, where Jane Austen spent the last eight years of her life. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The front of Chawton Cottage, where Jane Austen spent the last eight years of her life. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

How Edward Austen became Edward Knight: Austen’s Emma begins with a marriage between Emma’s governess, Miss Taylor and Mr. Weston, with Emma bemoaning the fact that her companion had now disappeared—moving a whole half mile away to her own house, her own husband, her own occupations. ‘…Emma was aware that great must be the difference between Mrs. Weston only half-a-mile from them, and a Miss Taylor in the house…’

Emma and Mr. Knightley (our eventual hero) commiserate with her father on the night of the wedding—that ‘sad business’ being that Miss Taylor very happily married Mr. Weston that day! Illustration by Chris Hammond in the 1898 Ruskin House edition of Emma.

Mr. Weston, even though he has kidnapped ‘poor Miss Taylor,’ still has something to offer to Emma. He has a son from an earlier marriage, all grown up now, brighter and more brilliant than any other young man, of course.

By himself, this son, Frank Churchill, wouldn’t have amounted to much, but, there are two things in his favor. One, he doesn’t live with his father at Highbury—so none of them have seen him yet, only heard of all of his glowing accomplishments and his handsome person, and that makes him more interesting than if they had known him since he was a child. Two, note the name change—Frank isn’t a Weston.

There’s a whole story behind that.

Mr. Weston’s first marriage was to a Miss Churchill, against the wishes of her very rich brother and sister-in-law, who objected to his profession, his social class, or they were just the sort of people who objected to everything. When the first wife died, the brother and sister-in-law Churchill (childless themselves) stepped forward with a proposition. They would adopt Mr. Weston’s child, Frank. They still harbored some resentment against Mr. Weston, and their terms were harsh. Frank would grow up in their house, as their child, and they would change his name and designate him heir to their vast fortunes. If Mr. Weston ‘could’ see his child at the beginning of this arrangement, over the years, the Churchills pushed him away steadily, so the visits dwindled, and Mr. Weston was relegated to merely being Frank’s biological father.

The handsome Frank Churchill, who ‘can sit down and write a fine flourishing letter.’ Mr. Knightley (the-under-Emma’s-nose-hero-while-she-is-distracted-by-others) isn’t impressed by Frank Churchill’s numerous letters to his father, Mr. Weston, promising to come, but never actually coming to Highbury to visit him. Illustration by Chris Hammond in the 1898 Ruskin House edition of Emma.

When Emma opens with the marriage between Mr. Weston and Miss Taylor, Emma’s governess, Frank Churchill has only briefly seen his father in London each year. Now, he’s no longer a child, so surely he must have more freedom to establish a better relationship with his father again despite any opposition from the Churchills? And his father is newly married; this then is the time to visit Highbury and pay his respects to his new stepmother?

Emma is consoled about the Weston/Taylor marriage by the idea of Frank Churchill coming to the neighborhood. He’s rich and handsome (so, it is said), and she herself is rich and handsome. The thought crosses her mind that they could very well make a match of it. Although our heroine doesn’t anticipate Frank Churchill’s arrival with the intent of falling in love with him…if it happens…well and good.

Frank Churchill does eventually arrive at Highbury, not (as we later find out) to pay his respects to his father’s new wife, the Miss Taylor that was, and not to meet Emma and see if she could be a potential wife for him. Here though, Mr. Weston, unaware of undercurrents, proudly introduces his son to Emma. Illustration by Chris Hammond in the 1898 Ruskin House edition of Emma.

Where did Jane Austen get this idea of the adopted offspring, kowtowing to his adoptive parents’ needs? To start with, this sort of adoption was a fairly common practice in Jane’s pre-Victorian England. If a wealthy, childless couple didn’t have children, where better to look for a child than in a relative’s family? That said relative would usually have had no problem producing children, eight, ten or twelve of them, and would be relieved, eager also, to have one of them adopted and consequently rich. Read Jane Austen’s novels, and then read her letters and you’ll see many, many coincidences and places where she’s borrowed from her own life/her extended social circle to put into her books. One such, is this Frank Churchill’s parentage.

The Church of St. Nicholas at Steventon, where George Austen was rector for thirty-seven years.

Art imitates life: Jane’s father George Austen had the living (rector for life, or until he voluntarily retreated from his duties and appointed a curate in his stead, which he did in 1801) of the two small parishes of Deane and Steventon in Hampshire. One living, Deane, was given to him by his uncle, the other, Steventon, by his cousin’s husband, Thomas May Knight. It’s likely, or at the very least reasonable to suppose that George Austen knew that he would benefit by these two livings before he took his orders and became a clergyman. (In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford, thinking herself in love with Edmund Bertram, tries to convince him to give up the church as a livelihood—it’s not ‘smart’ enough; a clergyman is too boring, too plodding, apt to run to fat as the years pass. Edmund, however, is quite fixed in his purpose; he won’t give it up even for love, besides, he has a living marked out for him, a steady, guaranteed income in a parish on one of his father’s estates (which will go to his older brother, who is heir). So much as Mary Crawford tries, she can’t convince Edmund to change to one of the other exciting professions like the army, the navy, or the law, in two of which a man would cut a dashing, thrilling figure in uniform.)

George Austen may not have had the choice of any other profession, but he almost certainly wouldn’t have taken up orders if the Deane and Steventon livings hadn’t already been promised to him. What George didn’t know when he first got the Steventon living, and moved to the rectory near the Church of St. Nicholas, is that Thomas May Knight’s son, called Thomas Knight, would become a steady, and welcome part of all of their lives.

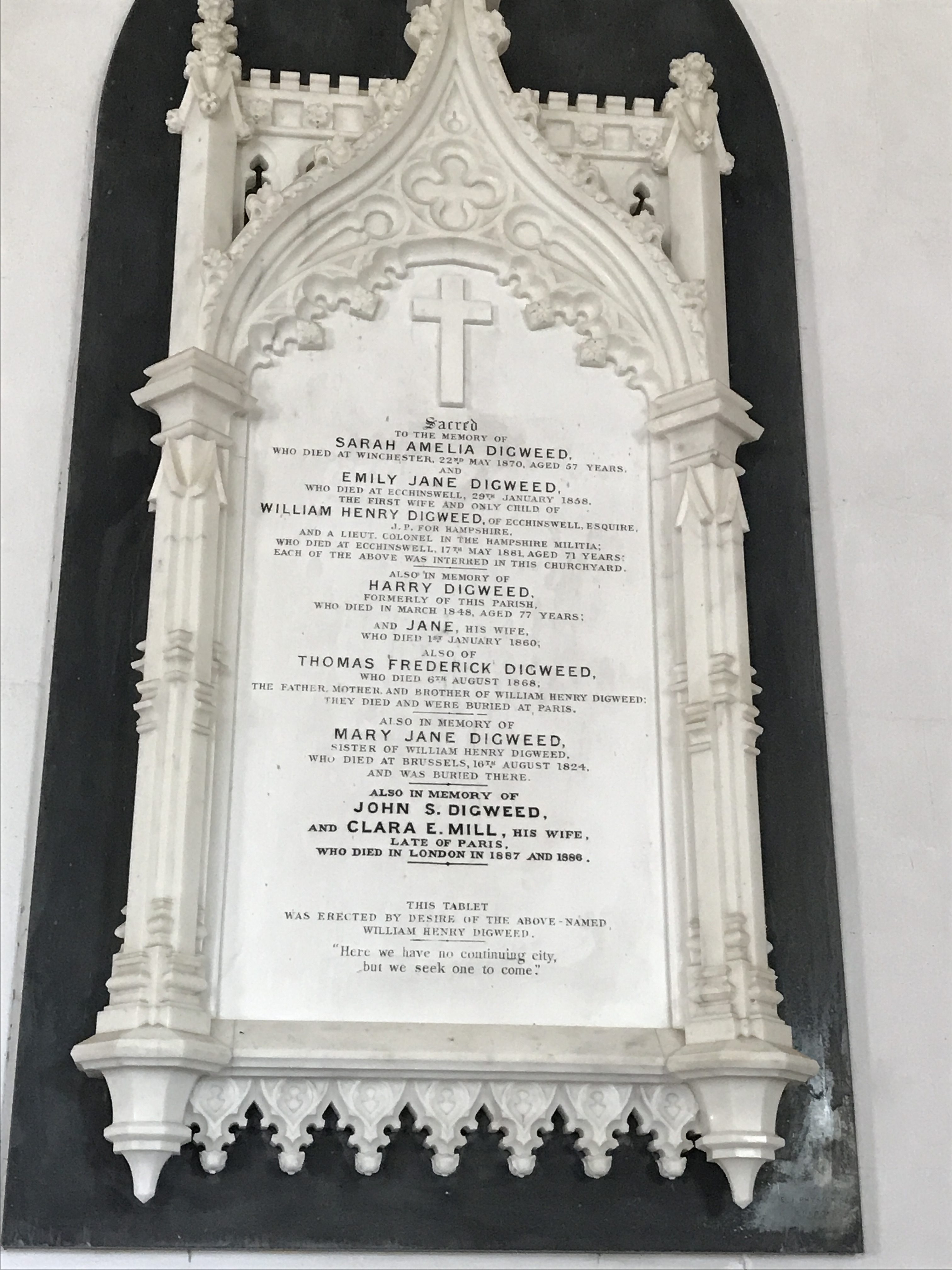

The wealthy Knights visit: Sometime in 1779, when Jane was three and a half or four years old, the newly-married son Thomas Knight and his wife, Catherine, set off on an extended tour of all of their estates. They owned, among other greater properties, the manor house at Steventon, which they had never lived in. For over fifty years, the Digweeds had rented Steventon Manor from the Knights, and were frequents visitors and guests at Steventon rectory, Jane’s home, which was a half mile from the manor toward the road leading to the village. Despite this proximity, while Jane mentions in a letter to her sister Cassandra that she’s certain one of the Digweed sons is in love with her, Jane herself doesn’t seem to have fallen in love with these close neighbors. The Digweeds, as generations-long occupiers of the manor, have a marble tablet dedicated to their memory in the Church of St. Nicholas in Steventon.

The Digweed memorial in the Church of St. Nicholas at Steventon.

The Steventon Manor house still stands today opposite the church where Jane’s father was rector, and where she prayed—it’s a private house now. But then, Thomas Knight owned it and of course, the living which his father gave to George Austen, and came on a trip in 1779 to see that all was well. He naturally visited his uncle in the rectory, and was introduced to all the Austen children, who would have been on their best behavior, neatly dressed and well-mannered, if for no reason other than the Knights were their benefactors.

Edward Austen was twelve years old that year. Neither the Austens nor the Knights knew it then, but it was a momentous meeting for all of them, frozen in time in a silhouette displayed at Chawton Cottage.

Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Edward is formally presented to the Knights, who are on the right-hand side, Catherine seated at the table, Thomas leaning against her chair. George Austen, Jane’s and Edward’s father introduces Edward. Also at the table, playing chess with Catherine Knight, is his sister, Jane Knight. (Note that Mrs. Austen has been left out of this adoption silhouette). And quite appropriately, Edward Austen, in his knee breeches and his tight coat, stretches out his arms toward his new family.

There’s no way that silhouette is an actual representation of how that meeting panned out; it’s unlikely the twelve-year-old Edward enticed the Knights with this arms-out gesture. He would have been polite and formal. The silhouette was done well after Edward’s initial meeting with the Knights had had such great consequences for all the Austens–around the time of his formal adoption.

At that 1779 encounter—after watching Edward for a few days—Thomas Knight asked to take him with them on the tour of the remaining estates. George and Cassandra Austen agreed. They had seven children by then and they lived on George Austen’s income as a rector, a little more than £200. And probably another £150 or so with taking in students to live in their home and study with George Austen. The Knights were blindingly rich compared to them, making, quite possibly (I’m guessing based on Edward’s future income) somewhere close to £20,000 a year. And, they had no children. Well, it was early days yet–the Knights had just been married. Perhaps they would have no children. None at all. Nary a one. And then…who knew what was in the future?

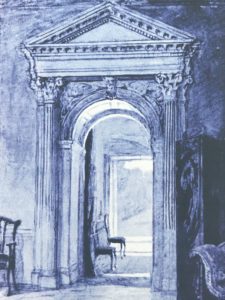

The hallway at Godmersham Park, one of the Knight estates, which later belonged to Edward Austen, Jane’s brother. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Mrs. Austen was the prime motivator of this intimacy with the Knights–so, at least, Jane’s brother Henry said in later years.

Cassandra Austen must have thought—what if Edward was adopted by the Knights? Made their heir? Some of the largesse would surely trickle down to the rest of the Austens; Edward could not, would not, forget his childhood home, his family, and his siblings.

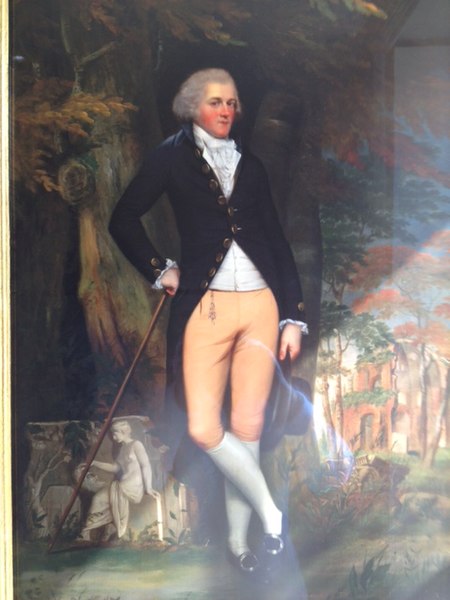

Edward Austen was a comely enough child, and much like Jane and her other siblings, courteous, kind, and well-mannered—in other words, they’d all been brought up well by their parents. There’s a portrait of Edward hanging in the front vestibule at Chawton Cottage which shows him as he was at the time of his adoption (so the little card near it says). But, Edward was sixteen years old when he was adopted by the Knights—this child is much younger, perhaps closer to twelve, when he was first seen by the Knights.

Edward Austen’s portrait, displayed in the front vestibule of Chawton Cottage.

That first meeting between the Knights and Edward led to more. Over the next four years, he spent his time between his home at Steventon rectory and wherever the Knights were. In 1783, the Knights formally adopted Edward. He still kept his last name of Austen, at least for now.

About ten years later, Thomas Knight died and left all of his property to his wife, Catherine Knight, with Edward still, eventual heir. For Edward, brought up by the Knights to consider himself heir to all the property, this interim period must have been…frustrating.

Godmersham Park in Kent, Edward’s primary residence, one of the three estates he inherited from the Knights. Source.

The inheritance comes but slowly, and not fully: If Frank Churchill’s experience in Emma is anything to go by—and, it’s obvious Jane Austen did borrow freely from her life and circumstances—then perhaps this almost-heir-at-my-beck-and-call situation with Catherine Knight didn’t sit very well with Edward Austen either–although he never showed it. Because, Frank Churchill in the novel is in a very similar place—adopted by rich relatives, their nominal heir whom they send on a tour of Europe (as the Knights did with Edward when he was eighteen) and still forced to be where they wanted him to be—all the riches, but little of the enjoyment of them.

Chawton House, another of Edward Austen’s inherited estates. Chawton Cottage, where Jane Austen lived, was attached to this estate. Source.

Catherine Knight takes a bite…out of the inheritance: Around 1798, after four years of running the large estates and managing everything herself, Catherine Knight decided to give up the inheritance to Edward. Her papers claimed it was out of generosity and love and affection for Edward, but—and there’s a big but here—she also reserved for herself the whopping sum of £2000 as an annual income, free of taxes or other encumbrances. Remember that the Austens, with eight children, lived comfortably (able to keep a carriage at least part-time etc.) on a top income, after many years of work, on something like £500.

It was a large amount to take from Edward, who had several children by then, had to pay taxes and all expenses—farmhands, labor, upkeep of buildings and parks, maintenance of livestock and farmlands—of the estates, and run and manage the properties. Catherine Knight was just a rich lady living by herself in solitary splendor.

Edward Austen. I think this was the portrait he had commissioned in Italy, while he was on his Grand Tour. Source.

Jane has some choice words on this semi-transfer of the estates to Edward in a letter to her sister Cassandra in 1799, that Catherine Knight giving Edward his inheritance “was no such prodigious act of Generosity after all it seems, for she has reserved herself an income out of it still;—this ought to be known, that her conduct may not be over-rated.” Whatever Jane might have felt, Edward was discreet, and put down nothing of his sentiments on paper.

I’ll speak a bit more about Jane Austen the person, the personality, what she looked like, what she was like in the Winchester Cathedral post, but this extract comes from a biography of Austen written by two other family members and published in 1913. The authors add a caveat to the playful or, even in this instance, the biting tone of Jane’s letter. That you must not judge her by her words; that she didn’t mean to not acknowledge Mrs. Knight’s generosity to Edward.

Hmmm…maybe. Jane was always fond of Mrs. Knight, and visited her often when she went to be with Edward, but read the rest of her letters and you will find her to be forthright and candid. Besides, she was writing to Cassandra, who would be sure not to share these caustic bits of her letters with anyone, so she was honest about her feelings. Little knowing that we would all be reading her innermost thoughts years later.

Chawton House today is called Chawton House Library, half a mile on Gosport Road from Chawton Cottage. Source.

Edward the Rich: So, anyhow, Edward now possessed his estates of Godmersham Park, Chawton and Winchester. He did not lose his interest in, or his affection for his family, even despite the riches. Jane and her sister Cassandra visited him often, stayed with him, and he supplemented their income after their father’s death. And then, in 1809, because the houses and cottages fell vacant, he offered them a place to stay more permanently either near Godmersham Park, or near Chawton. When they had made their choice of Chawton Cottage, Edward visited the cottage often with his steward to make improvements and arrangements that would be most comfortable for his mother and his two sisters. Being adopted by the Knights didn’t make Edward less fond of his Austens. Obviously.

Jane Austen, Cassandra, and their mother moved into Chawton Cottage in 1809. Jane’s longtime friend, Martha Lloyd, also came to stay with them; more on Martha on the next blog post on Chawton Cottage. This was finally home for Jane, and she would live here until she died.

And here, her writing restarted in earnest. Chawton Cottage gave us the early novels (finally) in print, and the newer ones were written here—Persuasion, Mansfield Park and Emma.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—we go inside Chawton Cottage—At Home at Last: Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage—Part 3

Looking forward to the next installment!

I’ve no idea how to put a thumbs up sign here, but that is what I want to say!