The Roman Baths that were:

The Roman Baths today don’t any longer function as usable baths. Waters are still pumped through ancient lead pipes into the bath, but they’re green with algae (pretty, actually!)–a sign that it’s not a good idea to try drinking it, or even trailing your fingers through it.

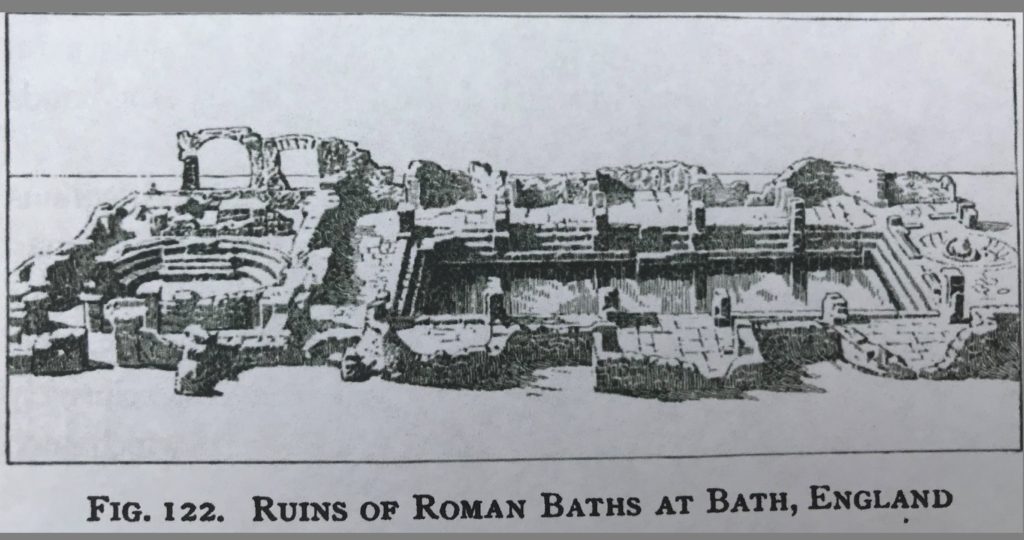

Source: Outlines of European History by James Henry Breasted. 1914.

They were, however, used extensively during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The Baths were discovered in 1755, mostly, as you see in the sketch above, the Great Bath and the circular cold-water pool. Nothing above the level of the baths.

The commercial possibilities were endless. So, pillars were built and terraces raised above them, with statues of Roman emperors placed around—what you will see when you visit today.

Very soon, Bath, its waters for drinking and bathing, became a thriving industry. The drinking waters were still touted as magical and the bathing was said to clear skin ailments and create a general well-being.

Georgian England came in droves to Bath and it became a very popular watering hole, with its society, its ‘season,’ and its Assembly Rooms, where the young lovelies and the handsomes met, danced, and courted.

This was Jane Austen’s era. And, she visited the Upper and Lower Assembly Rooms often for balls. (I’ve written several blog posts on Austen; the links should take you to the first parts and you can jump to the subsequent ones from there–Steventon Part 1; Chawton Cottage Part 1 and Winchester Cathedral Part 1).

The Pump Room

If the waters are beneficial, there has to be someplace to buy and drink it? And so, came the unimaginatively named Pump Room.

The Assembly Rooms were for the evenings; if anyone wanted to see and be seen during the day (and you wanted to very much if you had an ounce of social ambition of any sort), they went to the Pump Room.

Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Built in 1796, it was a single, large room, eighty-five in length, fifty-six feet wide, with a towering thirty-four-foot ceiling.

On the eastern end was a statue of Beau Nash, the local Bath dandy, the monarch of fashion, the man whose word could make or break you socially. His title was Master of Ceremonies for Bath and he constructed the Assembly Rooms and had strict rules for how many dances, at what intervals, when tea was served, and when the music stopped for the night. Gentlemen were not allowed into the dances in boots and women could not come in their aprons!

Nash brought order to Bath with his rules, silly as they may seem. He drove around in a carriage with six black horses, and splendidly dressed lackeys. He always wore a white hat, and after a while, it became his ‘crown;’ no one else wore one.

But his interest lay not just in the rich and the stylish; Nash helped build and fund the Mineral Water Hospital to provide the healing waters to the old, the sick, the infirm and the poor. He was so influential, that by the time the Pump Room was built and his statue installed within, Nash had been dead for almost thirty years.

Painting by Thomas Rowlandson. Source.

On the western end was a recess for an orchestra. The Pump Room is the only functioning part of the whole Roman Baths today and it is a restaurant with, actually, a fine menu. According to their website, a string quartet plays there every day—has been since the original Pump Room was made. That’s quite a feat.

The original Pump Room was open from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. every weekday, and directly inside the main entrance was the water fountain from which people could drink the mineral waters at a steady 114 degrees Fahrenheit.

Source.

If you’ve been reading along as I’ve posted on this blog, we visited two places that Jane Austen lived at, and her grave in Winchester Cathedral. (Check the Jane Austen tags.) Austen put the Pump Room into two of her novels, Northanger Abbey and the end of Persuasion. She lived at Bath for a while from about 1801 to 1805, and had also visited there before. She knew this original Pump Room, accompanied her uncle, James Leigh Perrot, for his daily glass of the waters, went there to socialize and meet people and store away impressions for her books.

The King’s Bath and the Queen’s Bath:

Once you’ve drunk the waters, it’s time to wander into the actual baths and dunk yourself. Genteel pre—and Victorian ladies and gentlemen probably preferred getting their health through glasses of warm water, but the option was there for a dip.

The two baths were in the same building as the Pump Room—the Pump Room faced north; the baths faced west onto Stall Street. There was also an entry into the baths from the Pump Room.

There were private and public baths in this building. On the ground floor were the public baths, and I think the open-air pool is identified as the Sacred Spring (when you visit today) was the public King’s Bath—it is overlooked by the windows of the Pump Room restaurant.

On the top floor of the baths building were the private baths, and quite lush they were too, lined with porcelain tiles, with sumptuously appointed dressing rooms and closets to keep belongings. The mineral water was pumped from below and there were also cold water taps for a quick splash if someone got too heated.

The building also had two ‘douche rooms,’ where the clients stood and were pummeled with water from a faucet or a showerhead for a water massage of sorts. And, on the side was a steam room and a sauna.

A spiral staircase led down to the public King’s Bath which was a large pool with a public space and partly glazed doors which could be closed on one end to provide privacy to bathers.

On one side was the statue of King Bladud—the one who was cured, along with his pigs, of leprosy from wallowing in the hot mud of the mineral springs. See Part 1. Turns out, it’s not King Bladud at all, but the statue was originally of King Edward III, and was taken down and altered a little to represent what Bladud must have looked like, and then put in the King’s Bath. So, the story goes.

Source.

The Queen’s Bath was named after Queen Anne, wife of James I, either because she did not want to bathe in the King’s Bath, or because she just wanted a bath in her name. The private part of the Queen’s Bath was fairly elaborate with a fountain for drinking the waters, fireplaces in the rooms, dressing rooms, a steam room and shower and of course, the bathing pools.

The pre-and Victorian swimsuit…

…was nothing like it is today.

To bathe, people rose early; the baths were open between 6 a.m. and 9 a.m. There, they changed into their ‘swimsuits.’ For men, it was a canvas waistcoat and drawers, and a linen cap. Women wore a canvas gown and petticoat, with pieces of lead sewn into the bottom hem, to keep the skirt from floating about their waists.

Bathing simply meant wading around in the waters, while attendants waited upon the clients. The bathers carried japanned bowls tethered around their necks with ribbons, which floated in the water in front of them. These would hold all sorts of necessities: handkerchiefs, perfumes, smelling salts maybe, and even cups of hot chocolate.

The Other Baths:

Across the street from the Pump Room was the Cross Bath, cheap and public. It had another pump room (presumably also cheaper than the more fashionable Pump Room) attached to it.

For invalids who could not come to the baths for their health, the water was carried to their houses and poured into their hip baths, still warm at about a hundred degrees Fahrenheit.

Thus did the town of Bath thrive on its Bath waters.

Although it doesn’t exist anymore either, right next to the Roman Baths were the Kingston Baths. This was constructed after the Priory House of Bath Abbey was demolished, sometime in the early 1700s, which also led to the discovery of Roman baths below the Priory House and some Roman artifacts, along with the spring of mineral water.

The Kingston Baths were the first private baths in Bath, constructed around 1763 by the Duke of Kingston. This was as elaborate as the Roman Baths complex, with its own pump room, wheelchair access, reclining baths, steam rooms, saunas and heated linen closets.

The Roman Baths today…

…are a tourist attraction, just that. About forty years ago, the waters were found to be infected, and the baths were closed for public bathing. The Pump Room is a restaurant now, with, as I mentioned, a lovely menu, and of course glasses of the warm mineral waters.

Almost the first place you see upon stepping into the complex is the Great Bath with its green waters and the whole upper terrace held up by pillars (all of which date to the 18th and 19th Centuries). On the terrace are statues of Roman emperors, also of recent construction, but the set the mood for what you’ll see below.

From the terrace, you look down into the Great Bath, but there are little rooms on that level with the remains of the dressing rooms, the cold-water pool, the Sacred Spring, and the saunas with their raised, heated floors.

Water pumps out from the natural hot springs at a steady 115 degrees Fahrenheit. The Great Bath is fed from the waters of the Sacred Spring (that is the source). The Great Bath is a lead-lined pool at a depth of about 5 feet, just deep enough for walking. The walls of the bath would have had shelves and platforms to sit on while immersed in the waters.

To the west of the Great Bath is the circular cold-water pool. In Roman times there would have been another structure, a great room with a large dome covering this bath.

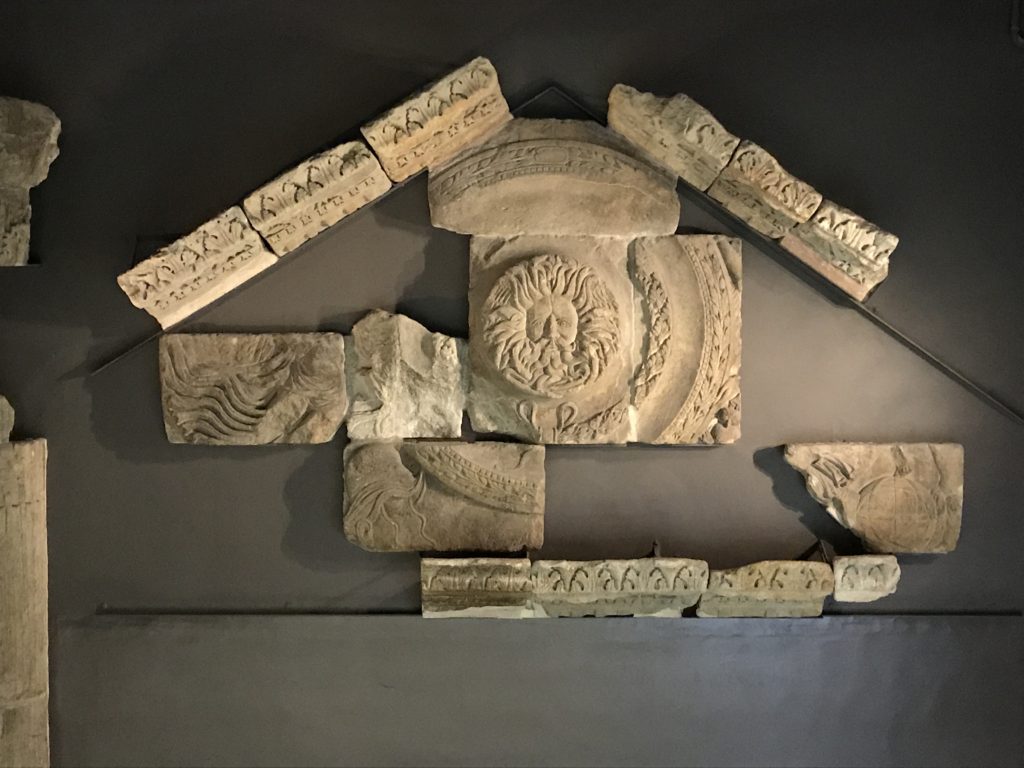

One part of the Roman Baths is a museum, with the temple pediment that was discovered in one of the excavations, which most likely hung over the main entrance to the temple to Minerva. It’s quite spectacularly conserved, along with the Roman coins and coffins.

There’s also a raised walkway over the remains of the temple to Minerva, in site. It’s a little piece of beautifully preserved history, all hidden from the street—from the outside, most you can see are the Roman statues on the terrace, the front entrance, and the Pump Room.

There’s no swimming in the Roman Bath waters, but a spanking new spa is just a minute’s walk away from here, with clean pools and pure water.

The new spa was tempting, but we had places to go that day, no time to lounge around. And so, we exited the Roman Baths—again, like Disneyland, through the gift shop!—went right back around the corner, past the entrance to the Roman Baths and to Bath Abbey, slumbering in the sunlight.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—The torrid history of the Bath bishops and monks—Bath Abbey–A Storied History–Part 1.

3 Replies to “The Roman Baths at Bath–Healing Waters—Part 2”